Overtly Muslim and covertly Jewish, and blending Jewish, Christian and Islamic beliefs and rituals, the Donmes were one of the most secretive sects in the Ottoman Empire and its successor state, the republic of Turkey. A closed, tight-knit community bound by the Eighteen Commandments — a set of strict social and religious guidelines — they created a parallel universe and maintained an impenetrable silence concerning their views and practices.

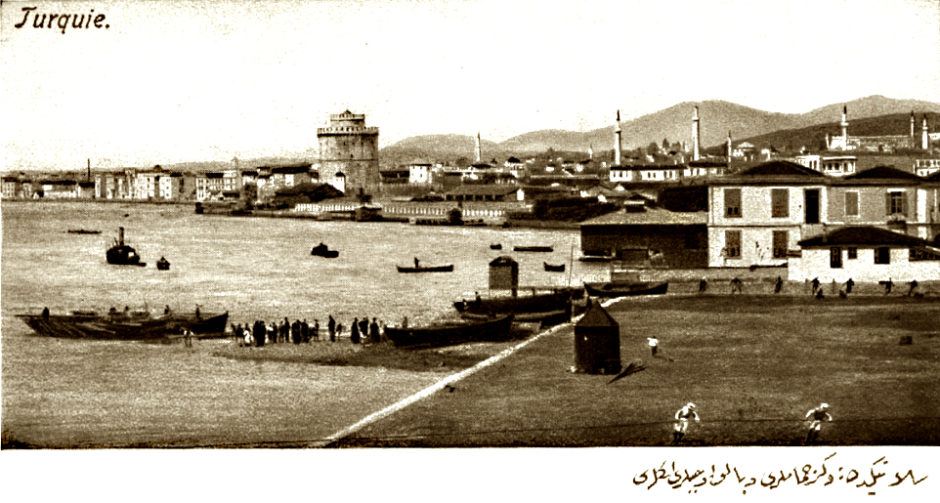

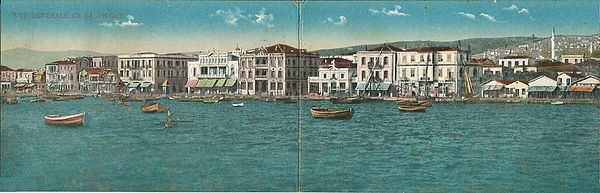

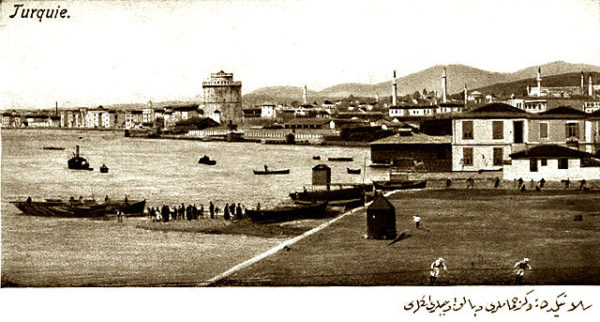

Living primarily in Salonica, Istanbul and Izmir until the early 1920s, the Donmes were successful in business, the arts and politics. The founding father of modern Turkey, Mustafa Kemal (Ataturk), was rumored to be a Donme. Conspiracy theorists in Turkey claimed they were a secret branch of world Jewry or, alternatively, Zionists who had undermined the Ottoman Empire.

Cengiz Sisman, a Turkish scholar who teaches history at the University of Houston, traces their origins from the 17th century up to the present day in an endlessly fascinating book, The Burden of Silence: Sabbatai Sevi and the Evolution of the Ottoman-Turkish Donmes, published by Oxford University Press.

As he points out, the Donmes, members of a Sabbatean mass movement founded by the ordained rabbi Sabbatai Sevi in Jerusalem in 1665, emerged during a period of increasing economic, political and religious instability. Born in Izmir in 1626, he proclaimed himself the long-awaited messiah in 1648. Sevi’s heretical ideas and activities angered both Jewish and Muslim authorities, and in 1666 he was imprisoned in a fortress on the Dardanelles. Accused of sedition, he was tried in Edirne in the presence of the sultan.

Offered a choice of conversion to Islam or death, Sevi chose to become a Muslim, a development that transformed his movement into an underground sect. Changing his name to Aziz Mehmed Efendi and subsequently to Sabbatai Mehmet Sevi, he accepted an honorary position in the sultan’s palace.

Due to his apostasy, the majority of his acolytes turned against him, but a small group of messianic hardcore believers, consisting of about 200 families, followed his path to Islam and became the nucleus of the Donme sect.

Never regretting his conversion, Sevi spent most of his time in Edirne, Istanbul and Salonica, sharing his “secrets” with his followers.

Muslims thought that the Donmes were insincere converts. Visiting Salonica in the 18th century, a French missionary wrote that they were “held in contempt by both Christians and Turks,” retaining “a secret inclination to Judaism, to the point of reciting their old prayers instead of those from the Koran.” Responding to that skepticism and scorn, they made a public show of their fealty to Islam, attending prayers in mosques and Sufi convents, performing the pilgrimage to Mecca and organizing rigorously Islamic funerals.

Until a population exchange between Turkey and Greece in 1924, Salonica — the Jerusalem of the Balkans — was the main center of the Donmes. There they dominated the tobacco, textile and silk businesses and held political positions reserved for only Muslims.

By the end of the 17th century, the Donme community was composed of about 600 families, some of which were originally from Poland. These Polish Sabbateans were led by Jacob Frank, a frequent visitor to Salonica and a convert to Islam. Eventually, Frank and many of the Frankists converted to Christianity in a mass ceremony. They lived mainly in Warsaw, Prague and Offenbach, practicing a crypto-Jewish life within the framework of Roman Catholicism. Adam Mickiewicz, the famous Polish poet, is believed to have come from such a Frankist family.

As for the Donmes, they formed a distinct community which subscribed to the Eighteen Commandments. “Although there are some Jewish elements in the commandments, they have almost no Islamic flavor,” writes Sisman.

Its rules and regulations were revised by each of the Donme subsects in accordance with their needs. There were three such subsects — Yakubi, Karakas and Kapanci. After the 19th century, each of them split along the lines of orthodox, reformist and assimilationist tendencies.

Judging by the commandments, which are reproduced in the book, the Donmes were secret Jews. As the eleventh commandment states, “Your first duty is to simulate the quality of being Muslim, and to stay entirely Jewish in your innermost (world).” As well, they were allowed to marry only Donmes, not Muslims or Jews, and they assumed two names: a Turkish one for everyday use and a Jewish one for use within their community. They mostly lived in certain neighborhoods where, as one writer quoted by Sisman noted, no one could “disturb or observe their practices.”

By the 19th century, the Donmes had become leading figures in Turkish language, literature and journalism, though most of them still retained a knowledge of Hebrew and Ladino. By the mid-20th century, however, virtually all the Donmes had forgotten these familiar languages.

“Donme visibility brought new challenges to their lives,” says Sisman. “The official Ottoman attitude toward them was still neutral at the end of the 19th century, but among the general population there was growing suspicion, resentment and even jealousy toward them due to their prominence in the transformation of Salonica.”

Pious Muslims portrayed the Donmes as secretive, crypto-Jewish, pretenders, anti-Islamic and tricksters, he adds.

The Jewish attitude toward them was equally scathing. In 1914, the chief rabbi of Istanbul accused them of immorality, sexual perversity, infidelity, financial impropriety and lack of ethics.

During the Tanzimat era toward the end of the 19th century, liberal-minded Donmes abandoned their religious identities and adopted the new secular supra-Ottoman identity, joining the ranks of Freemasons, the Young Turks, and later, the Committee for Union and Progress. Reformist Donmes remained in the fold, but sought to modify their ways. Orthodox Donmes tried to preserve their old traditions.

As Sisman suggests, Donmes of a liberal bent were drawn to politics, particularly in the first decades of the last century. Mehmet Cavid and Faik Nuzet (Terem) both served as ministers of finance. Mustafa Arif (Deymer) was minister of the interior in 1918 and minister of education in 1921. Tevfik Rustu (Aras) was Turkey’s first foreign minister, holding the post from 1923 to 1939.

With the formation of Turkey after World War I, all citizens were expected to acquire a strong nationalist and secular worldview. The Donmes publicly adopted this new identity, but behind the scenes, there was intense strife between the community’s various strains. In private, some of them hewed to their ethnic and religious crypto identity. Others kept only their ethnic identity. Still others opted for various forms of assimilation. Over time, however, the assimilationists became the largest and most dominant stream.

The Yakuza and Kapanci sects generally chose the path of full assimilation into Turkish Muslim culture. A considerable number of Karakas preserved their private ethnographic-religious identity.

As time went on, most Donmes joined the Turkish elite. “Except for the dwindling orthodox community, the majority chose to forget their ethnic and religious backgrounds and memories,” says Sisman.

The creme de la creme of Donme society were deputies in Turkey’s parliament, university professors, writers, poets, surgeons and lawyers. But in 1942, they were subjected to the infamous Wealth Tax imposed on minorities and foreigners.

Despite this blow to their dignity, the vast majority of Donmes have been fully assimilated. A few have returned to Judaism, and several thousand, primarily Karakas, survive as true believers.

There are about 60,000 to 70,000 persons of Donme descent in Turkey today and perhaps another 10,000, mostly in Europe and North America. “It is hard to know how many of them are ‘pure’ Donme on both their maternal and paternal sides, since mixed marriages became a common phenomenon in the second half of the 20th century, especially among the Yakubis and Kapancis,” writes Sisman. “Of those cultural Donmes, only 3,000 to 4,000, mostly Karakas, are thought to remain actual believers who hold onto their distinct ethnographic-religious identity, as reflected in their neatly prepared religious calendars, cookbooks, tombstones and cemeteries. For the majority of the Donme descendants, the Donme past is limited to family history, memory and nostalgia, devoid of its sacred connotations.”

But even they prefer to frequent the same social circles and clubs, attend certain schools and reside in specific neighborhoods, he notes.