I’m writing this from Czestochowa, Poland, where I was born 72 years ago.

The city is best known for the Jasna Gora monastery. Visited by around four million pilgrims per year, it is a shrine to the Virgin Mary.

The cloister houses the Black Madonna, one of the holiest icons of the Catholic Church. My wife and I had a close-up view of it on a tour, and it is indeed a magnificent work of art. Photographs don’t capture its splendor.

My parents, native to the city, were freed from a Nazi labor camp by the Red Army in January 1945. We all left Poland in 1946, and I’ve only been back once, 40 years ago.

Back then, it was a Communist country and tourism was not high on its list of priorities. It was hard to even obtain information about its history, including the Holocaust, in which some 90 percent of the Jewish population was murdered by the German occupiers.

Things are different now, and historical sites are well marked, tourist guides are everywhere, and the history of its once major Jewish community is recognized and even celebrated. Bus tour guides point out the former Jewish ghetto and recount its history.

Czestochowa was an important center of Jewish activity before World War II, and the community prospered.

All this changed on September 3, 1939, when German troops occupied the city. At the time, Czestochowa was home to 29,000 Jews, out of a population of 138,000. Soon enough, the persecution of the Jewish population began.

In August of 1941, the overcrowded Jewish ghetto was hermetically sealed off from the rest of Czestochowa. In 1942, more than 20,000 people were forcibly transferred from neighboring towns, raising the Jewish population to over 50,000.

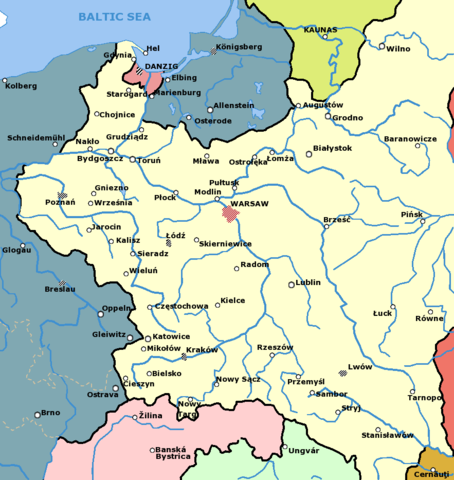

It turned Czestochowa into the third largest ghetto in conquered Poland after Warsaw and Lodz.

Between September 22 and October 7, 1942, most of the city’s Jews were packed into trains and sent to their deaths in the Treblinka death camp.

By 1943, only 3,990 Jews (including my parents) were still alive, all of them working in the HASAG-Pelcery munitions factory as slave laborers.

When the Red Army liberated Czestochowa on January 17, 1945, some 1,500 Jews from Czestochowa remained alive in HASAG.

In Czestochowa, where in 1977 it was almost impossible to even locate the Jewish cemetery, there is now a Jewish Museum, opened last year, on Ulica Katedraina.

It spans three centuries of Jewish contributions to all aspects of life in the city, with particular emphasis on the 20th century.

It also serves as a venue for various events, including academic conferences and reunions of descendants of Czestochower Jews visiting the city.

The Jewish Social Club (TSKZ), a community hub, is located at Ulica Generala Jana Henryka Dabrowskiego.

As for the Jewish cemetery, it now includes memorials at the mass graves of Jews killed during the 1943 uprising by the Jewish Combat Organization. My mother’s two brothers were shot by the SS at that time.

We walked around the area that served as the Jewish ghetto during the Holocaust. Among the monuments located there is the Umschlagplatz Memorial on Ulica Strazacka, unveiled in 2009.

This was the place, near the Warta train station, from where the city’s Jews were sent to their deaths at Treblinka.

The brick monument resembles a ghetto wall on which a large Star of David is mounted and is situated in the spot where daily round-ups and deportations took place. It was designed by the Czestochowa-born artist Samuel Willenberg, one of the last survivors of the 1943 uprising in Treblinka.

At Bohaterow Getta Square, a plaque recalls the members of the Jewish Combat Organization who died fighting the Germans. Ulica Kawia, the site of mass executions of Jews, also has various plaques commemorating some 4,000 murdered victims.

We also went to Warsawska 13, where my parents had lived before the Nazis, and Aleja Wolnosci 19, where they were housed in 1945-46, after their liberation (along with me, born after the war).

The ruins of HASAG-Pelcery still stand, a massive brick and mortar compound on Ulica Filmatow, in an obscure part of the city.

A plaque, in English, Hebrew, Polish,and Yiddish, was placed on an outer wall in 2009 “In memory of the Jews who suffered and died in the German forced labor camp in the Hasag-Pelcery ammunition factory 1942-1945.”

The ruin looks as sinister and as evil as I would have imagined, like something out of a horror movie. It’s in an ugly industrial area, there are no signs leading to it, and you can feel the suffering.

It was palpable, in the very air, as if the bricks had absorbed the tragedy that had unfolded here.

Perhaps it sums up in graphic form the cataclysm that befell the city’s Jews.

Henry Srebrnik, a professor of political science at the University of Prince Edward Island, is currently visiting Poland.