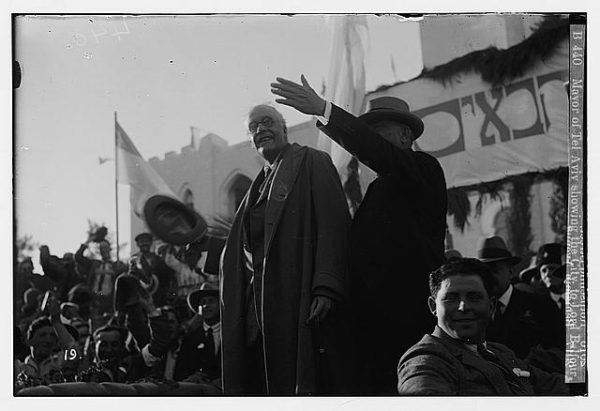

This year marks the 100th anniversary of one of the seminal events of the 20th century: the release of the Balfour Declaration.

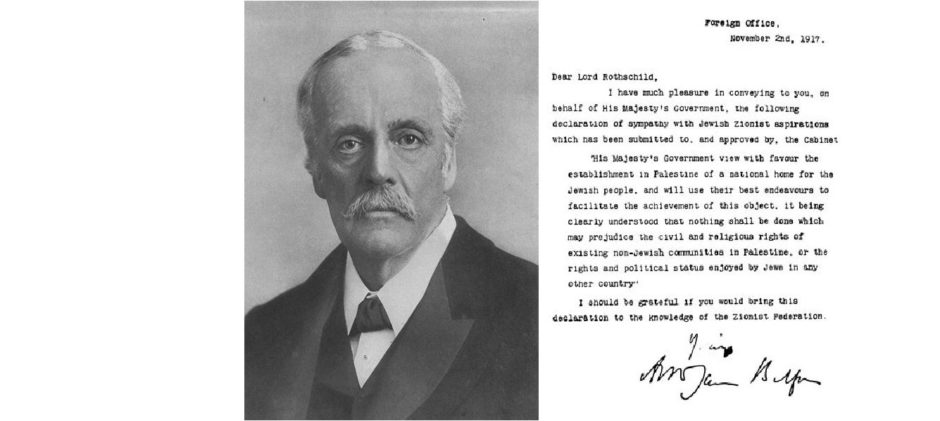

There are few documents in Middle Eastern history which have had as much influence as the Balfour Declaration. It was sent as a 67-word statement contained within the short letter addressed by British Foreign Secretary Arthur Balfour to Lord Rothschild, a prominent British Jew and Zionist activist, on November 2, 1917.

Before that date, Zionism was still a marginal movement that divided Jews and was little noticed by others. After the Balfour Declaration, the Jewish national project enjoyed the support of the leading imperial power of the age. In the letter, the British government stated its intention to endorse the establishment of a Jewish home in Palestine:

“His Majesty’s Government view with favour the establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people, and will use their best endeavors to facilitate the achievement of this object, it being clearly understood that nothing shall be done which may prejudice the civil and religious rights of existing non-Jewish communities in Palestine or the rights and political status enjoyed by Jews in any other country.”

The Declaration emerged as part of Britain’s growing desperation to seek allies in the ongoing bloodbath of World War I.

The Arab movement was first to secure British support, as a way of countering the Ottoman Empire’s call for a religious war against the British and French in their colonies, whose populations, especially India, included tens of millions of Muslims. Hence the decision that was made in Whitehall to encourage the Arab Revolt against the Turks, initiated by Hussein ibn Ali, Sharif of Mecca, in June 1916.

The Zionists had a much harder time engaging the interest of British officials at first. As late as 1913, the chief diplomat of the World Zionist Organization, Nahum Sokolow, could get a hearing at no higher a level than low-level Foreign Office functionaries.

Many in the Anglo-Jewish elite themselves opposed political Zionism. Edwin Samuel Montagu, for example, a minister in the British government at the time, denied there was a Jewish nation. “When the Jews are told that Palestine is their national home, every country will immediately desire to get rid of its Jewish citizens, and you will find a population in Palestine driving out its present inhabitants.”

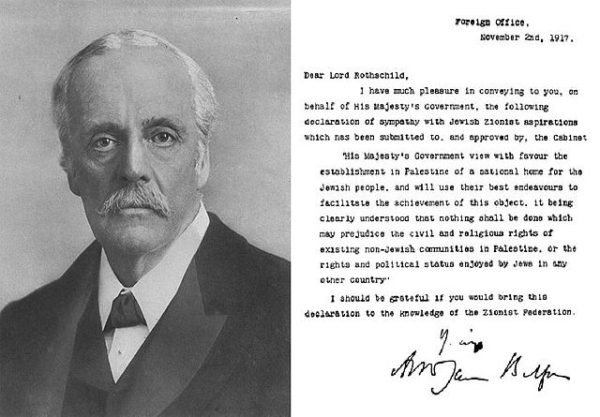

Much credit for turning things around is ascribed to Chaim Weizmann, the Russian-born Zionist who, as a scientist at the University of Manchester, helped the British war effort by developing a new method for the manufacture of acetone, used in the manufacture of cordite explosive propellants critical to the Allied war effort. But this alone would not have sufficed, of course.

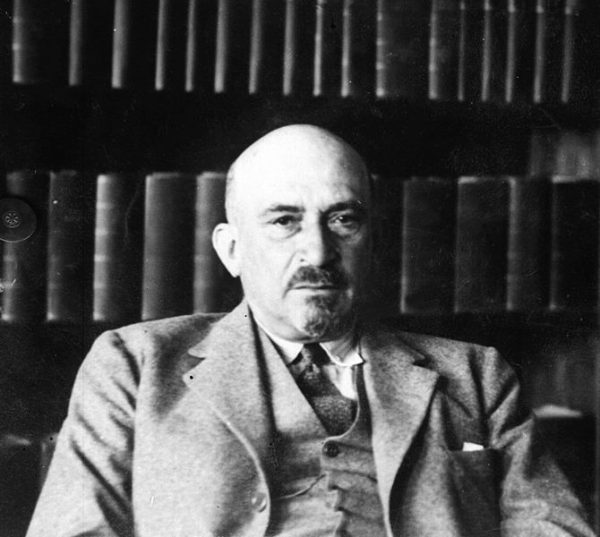

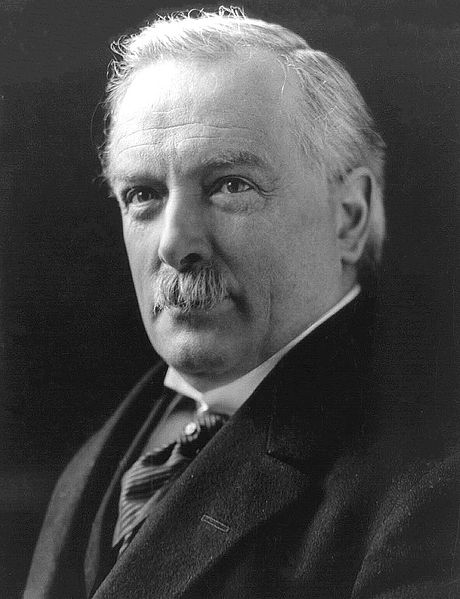

The truly decisive moment in paving the way to the Balfour Declaration took place on December 6, 1916, when British Prime Minister Herbert Henry Asquith was compelled to resign, and was replaced by David Lloyd George.

Asquith had no interest in Zionism and did not support the Zionist aspirations, but Lloyd George and his foreign secretary, Arthur Balfour, believed that support for Zionism would advance British war aims.

The problem, though, was that at the time many Jews in the United States tended to favor Germany, due to the fact that Britain was allied with tsarist Russia, home of anti-Jewish political and economic repression and pogroms.

But this changed in the spring of 1917, when, on March 15, Tsar Nicholas II abdicated and a liberal regime emerged in Russia.

Now, the British believed, American Jews could be persuaded to encourage their government to enter the war, and Russian Jews would also throw their weight behind efforts to ensure Germany’s defeat and the creation of a Jewish national home under British sponsorship.

Jewish influence, the British thought, would tilt the debate in Washington and St. Petersburg and could best be activated by the promise of a Jewish restoration to Palestine. They also worried that Germany might issue its own pro-Zionist declaration.

Moreover, support for Jewish nationalism might advance Britain’s territorial ambitions in Palestine.

In the spring of 1916, Britain, France, and Russia had finalized a secret agreement, commonly known as the Sykes-Picot accord, to partition the Ottoman Empire. But Lloyd George, who would become prime minister at the close of 1916, thought that the agreement had given too large a piece of Palestine to the French.

Britain, after all, would do nearly all of the expected fighting against Ottoman forces in the Sinai Peninsula and Palestine. He and Balfour saw an opportunity to use Zionism to gain international support to place the Holy Land entirely under British rule instead.

The Zionist Review described the declaration as “formal public recognition by Great Britain (and, that is, by the Allies) that Israel as a nation lives and persists.”

Following the end of the war, when Britain acquired a League of Nations Mandate over Palestine, its purpose was partially to put into effect the Balfour Declaration, in conjunction with the World Zionist Organization.

The Mandate specifically referred to “the historical connections of the Jewish people with Palestine” and to the moral validity of “reconstituting their National Home in that country.”

Furthermore, the British were instructed to “use their best endeavors to facilitate” Jewish immigration, to encourage settlement on the land and to “secure” the Jewish national home.

At the time, the vast majority of Palestine’s population consisted of Christian and Muslim Arabs, but Jewish settlement increased in the decades following 1917, as the Zionist project brought many Jews to the land.

The British would backtrack on these early promises. The British establishment itself was divided and began to respond negatively to Zionism by the late 1920s, in the face of Arab hostility to Jewish immigration.

By the mid-1930s, fearing that the Palestinian Arabs would side with Germany and Italy in a war they knew would soon come, Britain increasingly reneged on the declaration’s commitments. Indeed, at the moment European Jews were most desperate to seek entry to Palestine, the White Paper, issued on May 17 of 1939, virtually eliminated that possibility.

Jewish immigration to Palestine was limited to 75,000 for the first five years, subject to the country’s “economic absorptive capacity,” and would later be contingent on Arab consent. Stringent restrictions were imposed on land acquisition by Jews.

The Jewish Agency for Palestine issued a statement condemning the move, saying that the British were denying the Jewish people their rights in the “darkest hour of Jewish history.”

The Permanent Mandates Commission of the League of Nations concluded that the White Paper “was not in accordance with the interpretation which, in agreement with the mandatory power and the Council, the commission had always placed upon the Palestine mandate.” Not only did the British reinterpret the definition of a “national home” to preclude a state, they even denied that it meant a haven. But London did not relent, even as millions of Jews were killed by there Nazis throughout World War II.

Still, by the time the United Nations General Assembly on November 29, 1947 voted to partition Palestine into Arab and Jewish states, the Jewish population had reached one-third of the Mandate’s total of almost two million people.

Six months later, the State of Israel was born.

With the Balfour Declaration, Britain laid the foundations for a Jewish state — and a conflict between Arabs and Jews that a century later remains unresolved.

Henry Srebrnik is a professor of political science at the University of Prince Edward Island.