Mehnaz Afridi is appalled by two troubling phenomena in Muslim communities — the “lack of understanding” of the Holocaust and the “growing antisemitism.”

She should know.

An Indian Muslim born in Pakistan, she’s director of the Holocaust, Genocide and Interfaith Education Center at Manhattan College, a Catholic liberal arts institution in New York City.

It’s a position that seemed unsuited for a Muslim, she readily admits. But Afridi was up to the challenge and sought the post. “Perhaps I could serve as a bridge between the abyss that separates contemporary Jews and Muslims,” she writes in her refreshingly candid book, Shoah Through Muslim Eyes, published by Academic Studies Press. “To me, as a Muslim woman, any espousal of hatred is forbidden under not only secular laws but also Islamic principles.”

In this volume, she set out to achieve two objectives: “I hope that through this book, Jews may be humanized in Muslim eyes, and that the Shoah may be given its unique place in the list of genocides committed over the course of human history.”

Afridi’s interest in the Holocaust stems from personal experiences.

Her parents, displaced during the partition of India in 1947, became refugees and endured what she describes as “a hidden genocide.” After leaving India, they lived in Pakistan, Europe and Dubai. Afridi moved to the United States in 1984. “Being a minority in every country compelled me to understand the pain of others and dedicate my life to those who suffer under the oppression of racism and intolerance,” she says.

She adds: “As a Muslim in Pakistan, I was always caught between accepting Jews and rejecting Jews on the basis of anti-Israel political feelings within my family.” On the other hand, Afridi notes, her closeness to Islam — which she promotes as a religion of tolerance, self-examination and egalitarianism — was “intensified and inspired” by studying Judaism.

Afridi was also greatly influenced by an academic mentor in the department of religion at Syracuse University, Alan Berger. He asked her if she wanted to visit Israel and study at the Hebrew University in Jerusalem. As a Pakistani citizen, she was forbidden to set foot in Israel, but much to her family’s and friends’ chagrin, she went.

“My trip to Jerusalem changed my life,” she writes, saying she had “some deeply moving experiences that have shaped me in my approach to the conflict between Israel and Palestine.”

Afridi thinks Muslims should accept Israel as a state and the Holocaust as a unique historical event. She lists eight reasons why the Holocaust is unique. Afridi’s views, however, have isolated her from many Muslims, who dismiss her as a “Jew lover.”

She believes that Muslims, though not having been perpetrators during the Holocaust, have developed “a pattern of antisemitism.” In Muslim circles, Jews are invariably a “topic of conversation.” As she puts it, “Whether we were discussing economic failure in Dubai or bombings in Afghanistan, Jews lurked in the corners of the room like ghostly scapegoats. There was no reason or logic to this, but the Jews were instantly invoked, regardless. One of the enduring conspiracy theories was that Jews attacked New York City on September 11, 2001, and that all the Jews in the twin towers of the World Trade Center were safely evacuated — a ridiculous story, demonstrably untrue, but still a popular theory in some quarters today.”

Muslim antipathy toward Jew, she says, falls under two categories: Islamicized and secular nationalist antisemitism, both of which are harnessed by extremists. They contend that Jews lust for money and are intrinsically untrustworthy.

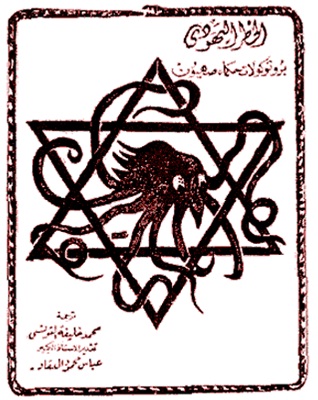

“The relationship between Jews and Muslims has disintegrated due to political upheaval in Israel and the Middle East and the disturbing ploy of seeing Jews as “other” within the Muslim world,” she goes on to say, adding that The Protocols of the Elders of Zion are widely circulated in Muslim countries.

Pakistani Muslims are particularly susceptible to antisemitism, she suggests. Jews there are regarded with “hatred and suspicion, and believed to be behind every bomb, outbreak of disease and war.”

Elaborating on this point, she says, “Antisemitism is everywhere, like smog that hangs in the air — thick, dirty and choking. Even in Karachi, where I was born, the Jews are everywhere, although they have not lived there as a community of any size in several hundred years. Hatred and suspicion of Jews is in the schoolroom, the pulpit, the media, and even in the butcher’s shop in the dense Karachi marketplace, where, as I recall, the butcher blamed the spread of the bird flu on Jews …”

Afridi calls for incorporating the Holocaust into the curricula of Muslim schools, but this is easier said than done. Many Muslims are of the view that Jews “used” the Holocaust to “colonize” Palestine, and that the Holocaust was the reason why Jews in Israel received political support from the United States and Europe. She also points out that Muslim educators refuse to allow their students to study any religion but Islam. “This problem creates a distance between Muslims and other faiths, allowing Muslims to interpret Jewish and Christian thought and belief strictly through the lens of Islam.”

If Muslim school children were exposed to the narrative of the Holocaust, she says, they would discover that Muslims lent assistance to Jews during their darkest hour.

Muslims in Albania assisted Jews. The Turkish diplomat Ulkumen Selahattin saved about 50 Jews on the island of Rhodes. The sultan of Morocco, Mohammed V, informed the pro-German Vichy authorities he would not implement certain antisemitic edicts.

These are very difficult issues, but if Jews and Muslims are prepared to meet each other half way, she believes, they could at least acknowledge each other’s history. “What is required is a deconstruction of Jews in the Muslim world, and vice-versa, so that Jews and Muslims will no longer rely on negative images of each other. We must realize that it will take more than dialogue, interfaith events and lectures to solve the problem.”

Exactly.