To no one’s surprise, Iranian officials conveniently blamed the latest outburst of anti-government protests in Iran, the most serious since 2009, on outside meddling.

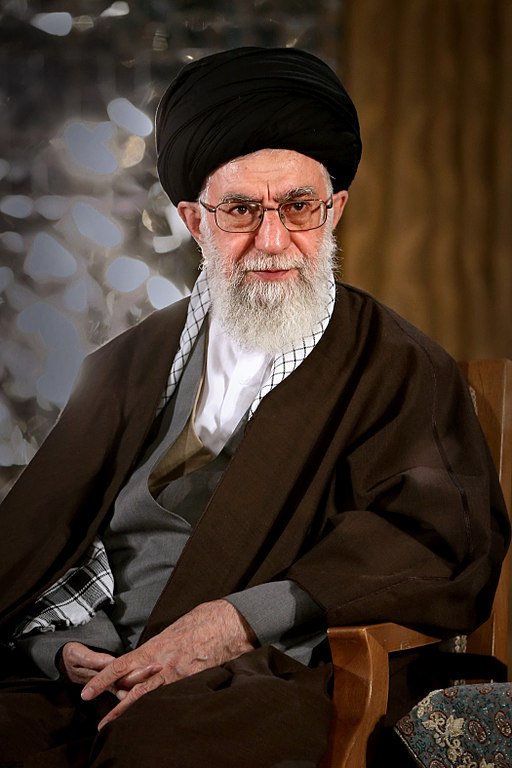

Iran’s supreme leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, accused external “enemies” of fomenting the nation-wide disturbances, which broke out on December 28 and have so far claimed the lives of 21 people. Iran’s chief prosecutor, Mohammed Jafar Montazeri, branded the United States, Israel and Saudi Arabia as the instigators. “The U.S., the Zionist regime and the Al Sauds were the three sides of this subversive plan,” he said.

Despite their bluster, Khamenei and Montazeri have reason to be paranoic. For centuries, Iran has been the object of foreign interference and aggression.

The Mongols invaded Persia in the 13th century. Russia conquered Persian territory in the 19th century. Britain occupied the western portion of the country during World War I. Britain and the Soviet Union mounted an invasion in 1941. In 1951, the democratically elected prime minister, Mohammed Mosaddegh, was deposed in a coup masterminded by the United States and Britain. In 1980, Iraq seized the Iranian province of Khuzestan, touching off the protracted Iraq-Iran War.

So, yes, historically speaking Iran has been in the cross-hairs of aggressors.

But the rioting that convulsed Iran cannot be ascribed to the United States, Israel or Saudi Arabia. While it is abundantly clear that their leaders would be ecstatic if Iran’s theocratic regime disappeared, there is no evidence that they played a role in the eruption of street demonstrations throughout Iran.

In certain respects, the new unrest was different than the protests that erupted nine years ago in Tehran and resulted in the deaths of about 150 Iranians and the arrest of thousands of civilians. Back then, the vast majority of protesters were reformers, members of the educated elite and residents of Tehran. This time around, they were from the periphery and tended to be blue-collar workers in their 20s and 30s directly affected by the catastrophically high unemployment rate, which hovers around 30 percent to 40 percent.

Another difference is that the disturbances in 2009 were spearheaded by two charismatic politicians, Hossein Mousavi and Mehdi Karroubi, who have been under house arrest since 2011. They had the temerity to question the outcome of the presidential election, which was won by Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, a hardliner, by means of alleged vote rigging.

By contrast, the current round of protests, which seem to have been repressed by the regime, were leaderless, but interestingly enough, they started in the hardline bastion of Mashhad, Iran’s second largest city (and the locale of an 1839 pogrom which forced members of the Jewish community to convert to Islam en masse). It would appear that hardliners in Mashhad — the home of two of Rouhani’s main rivals in last year’s election, Ebrahim Raisi and Mohammed Ghalibaf — tried to discredit President Hassan Rouhani, a relative moderate, by whipping up opposition to his reformist administration.

First elected in 2013, when the Iranian economy was burdened by international sanctions, Rouhani was reelected last year by a considerable margin after promising to increase the standard of living.

Rouhani’s opponents attempted to undermine him by focusing on the discontent that his economic policies have engendered. They leaked the contents of his proposed 2018 national budget to the media, And then they organized rallies against him. These demonstrations, however, spun out of control and spread to Isfahan, Shiraz, Tabriz and Qom, among other cities.

The proposals in the draft budget, calling for significant price increases and the slashing of subsidies on basic goods like food and fuel, infuriated working class Iranians struggling to earn a living. Their ire was doubly aroused by the fact that fabulously wealthy religious institutions, controlled by elements in the ruling elite, would be exempt from austerity cuts, heightening suspicions that the political system is corrupt and skewed against them.

Rouhani had assured supporters that the landmark agreement Iran signed with the six major powers in the summer of 2015 to freeze Iran’s nuclear program would be to their advantage as workers and consumers. It would provide Iran — a major oil producer — with sanctions relief to the tune of tens of billions of dollars, produce considerable trade benefits and bring in coveted foreign investments.

Much to the glee of hardliners, Rouhani was unable to deliver on most of his promises, though he is generally credited with having reduced the rate of inflation, which had been cutting steadily into workers’ meager salaries.

As far as protesters are concerned, economic issues were only part of the problem. In particular, they were concerned that Iran was recklessly siphoning off billions of dollars to finance various armed groups in the Middle East and the Syrian regime of President Bashar al-Assad.

Iranian surrogates like Hezbollah in Lebanon and Hamas in the Gaza Strip advance Iran’s regional interests, but at what price at home? Demonstrators have been seen carrying placards reading “Neither Gaza nor Lebanon, I will give my life for Iran.”

No one knows how long the current protests will last. In all likelihood, the regime will nip them in the bud before they completely get out of hand. In the meantime, the reactions of its top officials have been telling. Rouhani, a supposed reformer, initially said that Iranians are “completely free” to voice constructive criticism. On January 8, he elaborated. “The people have demands, some of which are economic, social and security-related, and all these demands should be heeded,” he said. No one, he added, is free from criticism. “We have no infallible officials and any authority can be criticized,” he declared.

But the head of the Iranian Revolutionary Guards, Mohammed Ali Jafari, a staunch backer of the Islamic republic, described the protesters as “seditious.” This can only mean that security forces under his command were planning a big crackdown that would spell finis to the protest movement.