The Ottoman era in the Middle East has been resurrected thanks to the creation of a popular tourist attraction in Tel Aviv near Jaffa. HaTachana, known in English as The Station, is a charming complex of shops, boutiques, cafes and restaurants in the southern part of this lively Israeli city.

Originally an Ottoman Turkish railway station, HaTachana was formerly the terminus of the Jerusalem-to-Jaffa railroad line. It was officially opened when Palestine was part of the sprawling Ottoman Empire.

A hub of commerce, it was in active service from 1892 until the first Arab-Israeli war in 1948. When the hostilities ended, the newly created state of Israel closed the Jaffa station and built a new one in Tel Aviv. Eventually, the old station fell into disrepair, a relic of the past.

About a decade ago, private investors bought the derelict station. In 2010, they converted it into a shopping and entertainment center spread over 20 hectares.

The structures that bring the 400-year Ottoman period back into sharp relief are the train station building, the freight terminal and the railway tracks. The faux tracks, which accommodate two beige-and-brown railway carriages, lead nowhere and are strictly for show, designed to remind visitors of a bygone epoch. Several of the buildings are foreign to the original site. One of them, the Villa, belonged to Hugo Wieland, a member of the German Templar community, which flourished in Palestine from the 1870s to the 1930s.

HaTachana is right across the street from a municipal beach facing the Mediterranean Sea and adjacent to Neve Tzedek, the first Jewish neighborhood outside Jaffa, which was predominantly Arab until 1948.

The Jerusalem-to-Jaffa railway line was the brainchild of British financier, banker and philanthropist Sir Moses Montefiore (1784-1885), an early Zionist who conceived the project in 1838, when Palestine was home to less than 50,000 Jews and Theodor Herzl, the founder of the modern Zionist movement, had not even been born.

Montefiore believed that a railroad would be a more efficient way to convey goods than the camel, the mainstay of transportation prior to the 20th century. The project died on the drawing board because costs would have been prohibitive and authorities in Constantinople feared that a railroad would serve Western rather than Ottoman interests.

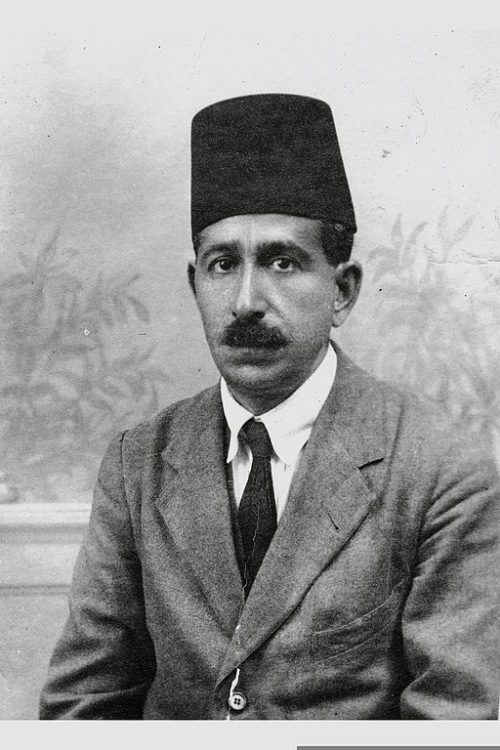

Joseph Navon (1858-1934), a Jerusalem businessman and a Jewish Ottoman citizen, revived the idea with the financial support of foreign investors from Europe. Herzl, in a letter, scoffed at the notion of a “wretched little line from Jerusalem to Jaffa,” claiming it would be “quite inadequate for our needs.”

Usually a visionary, Herzl was dead wrong in this instance. During its heyday before 1914, the railway line processed 43,000 tons of freight and handled 183,000 passengers annually. It was also of great benefit to the Zionist movement, having prompted one of its benefactors, Baron Edmond de Rothschild, to build Jewish settlements along the length of its tracks.

During these decades, thousands of evangelical Christians from Germany, the Templars, settled in Palestine, creating prosperous colonies. The Wielands, a Templar family, established a brick and tile factory near the station.

Hugo, the patriarch, constructed the Villa, a one-storey residence, in 1902 and added a second floor four years later. His descendants lived in it until the mid-1930s, when pro-Nazi Templars were expelled from Palestine by Britain.

During World War I, the railway line was commandeered by the Ottomans and their ally, Germany. With the signing of armistice agreements between Israel and its Arab neighbors in 1949, it lost its relevance. Having been supplanted by a railway terminal in 1950, it sank into decrepitude. But as southern Tel Aviv was gradually gentrified from the 1970s onward, real estate developers saw potential in the decaying station.

Five years in the making, HaTachana is now a place where you can grab a sandwich, sip a latte, lick an ice cream cone, enjoy a meal, buy a blouse or a pair of pants and purchase crafts, organic fruits and vegetables.

But above all, HaTachana takes you back to a time when locomotives belched black smoke, men wore fezzes and Israel was a glint in the eyes of Zionists.