German Jews found a “spiritual home” in German culture, philosophy, literature and music after their emancipation in 1871. During this period, when Germany was on the ascendancy as a great power, Germans generally related to Jews with a mixture of hospitality and hostility. In plain language, the tentative acceptance of Jews into German society was offset by the persistence of deeply-rooted antisemitism.

Prejudice against Jews was gradually tempered by the recognition that Jews had something concrete to offer Germany, the distinguished historian Fritz Stern writes in the new edition of Einstein’s German World, a book of essays published by Princeton University Press. Yet, as he notes, Jews were often treated as second-class citizens.

In Prussia, where most German Jews lived, they achieved success in free professions such as law and medicine, but were excluded from positions in universities, the officer corps of the armed forces and the higher ranks of the civil service. To Stern, they were “prosperous pariahs.”

Some assimilated Jews, eager to make the leap from legal emancipation to genuine equality, chose the path of conversion to Christianity. As an example, the cites the case of the renowned chemist Fritz Haber, who, at the age of 24 in 1892, was baptized, much to his father’s dismay. (Stern, who died in 2016, doesn’t bother to mention that his parents were also converts to Christianity, and that Haber was his godfather).

Still other secular German Jews, like the brilliant physicist and Nobel laureate Albert Einstein, remained Jewish. “He had no tie to the Jewish religion or Jewish rituals, but he never ceased being aware of his Jewish descent or of the antagonism that Jews — whether religious or agnostic — encountered in most parts of Europe,” says Stern.

He contends that German supporters of Jewish emancipation tacitly assumed that Jews would eventually convert. “It was a kind of unspoken bargain,” he writes.

Like many Jews of his kind, Haber — the recipient of the 1920 Nobel Prize — opted for Christianity for purely pragmatic reasons. As Stern observes, “He knew that conversion brought with it practical rewards in the form of greater social acceptance, but it also reinforced the ambiguities and ambivalences that marked the life of German Jews. Converted Jews faced the skepticism of their new co-religionists and the likely scorn of some of their old ones.”

Haber exemplified another truth. Like other converts, “he retained his consciousness of the Jews’ historic apartness…” And so it was less than surprising, he adds, that the majority of his friends were Jews or of Jewish descent.

For Haber, the accession of the Nazis to power in 1933 marked the end of his active career at the Kaiser-Wilhelm Institute in Berlin. “His letters to friends and family make clear that he understood the noose was ever tightening,” says Stern. Although Jewish academics lost their jobs after that date, Haber could have retained his post, at least for a while longer, had he been able to bear the thought that his Jewish colleagues would be summarily dismissed.

Haber died in 1934 during a visit to Switzerland. A year later, the German scientist Max Planck organized a memorial service for him, despite the protests of the Nazi regime.

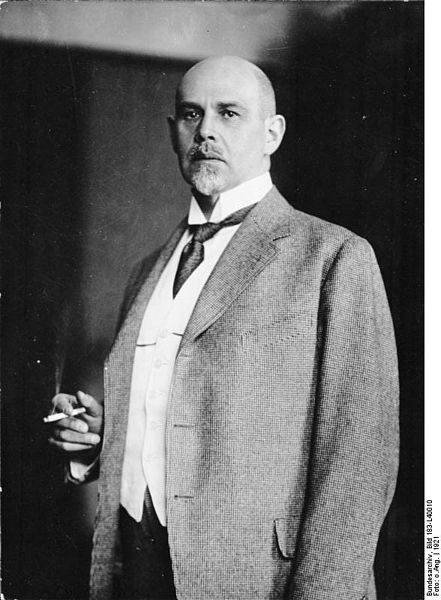

Stern’s essay on Walther Rathenau, Germany’s first and only Jewish foreign minister, also addresses the tension of being Jewish and German in 19th and 20th century Germany.

The scion of a rich industrialist, Rathenau was, as he points out, “very self-consciously German.” But there was a dark side to attachment to all things German. “Rathenau’s deepest ambivalence sprang from his Jewishness. Given his mockery of Jewish speech and customs and his vilification of the public conduct of wealthy German Jews, he has often been cited as a prime example of Germany Jewish self-hatred, an unappealing prototype of the servile German Jew. But he also felt deep pride in belonging to what he considered the Jewish race.”

He loved his country, but knew that rejection could be lurking around the corner. As he wrote in 1911: “In the youth of every German Jew, there comes a moment which he remembers with pain as long as he lives: when he becomes for the first time fully conscious of the fact that he has entered the world as a second-class citizen and that no amount of ability or merit can rid him of that status.”

Rathenau, however, was disdainful of conversion, considering it demeaning.

Rathenau hungered for a ministerial post, says Stern. “He knew that his intelligence, his experience, his perfect fluency in three languages far surpassed the abilities of other contenders. He also knew that his ambition … was thwarted by his Jewishness.”

With the outbreak of World War I in 1914, he was appointed to take charge of a department in the Ministry of War that controlled the supply and distribution of essential raw materials. He resigned a year later, disappointed at not having received the plum job he coveted. But in 1921, Chancellor Joseph Wirth appointed him Minister of Reconstruction, and in 1922, he named him foreign minister.

“None of this appealed to nationalists, let alone the radical right, who saw Rathenau as the very personification of Jewish power and betrayal,” says Stern.

By June of that year, Rathenau lay dead, having been assassinated by right-wing extremists.

As Stern suggests, Rathenau’s assassination was symptomatic of the ambiguous place Jews in Germany occupied in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.