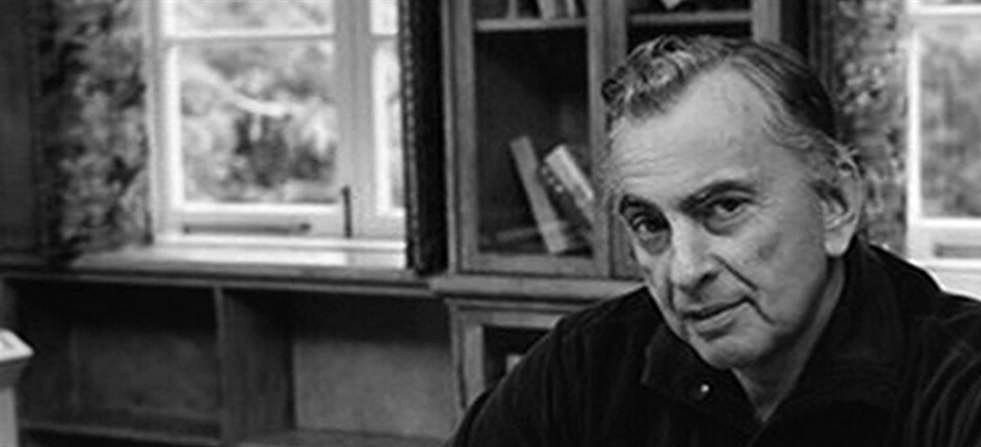

Gore Vidal, a son of privilege, left the American ruling class to become a constant thorn in its side. Through his novels, essays, plays and television appearances, he was a sharp critic of U.S. foreign policy and the “decadence” of political life in the United States.

Articulate and outspoken, he was a celebrity intellectual, a student of the American class system and a fervent believer in the thesis that the United States is a country for the rich.

Vidal, who died in 2012, is the subject of Nicolas Wrathall’s sympathetic but at times superficial documentary, Gore Vidal: The United States of Amnesia, which will be screened at the Bloor Hot Docs Cinema (506 Bloor West) on Wednesday, Dec. 4 at 6:30 p.m. and 9:15 p.m. and on Thursday, Dec. 5 at 6:45 p.m.

Describing him as “a writer of constant courage,” Wrathall views Vidal through the lens of his fecund career as a literary figure, his reputation as a public iconoclast and his dual sexual identity.

Born in 1925 with a silver spoon in his mouth, Vidal was a patrician. His father was a high-level official in President Franklin Roosevelt’s administration, while his mother was an alcoholic who had little time for her precocious son.

Since he rarely saw his father and had a “horrendous” relationship with his mother, the person closest to him was his grandfather, Thomas, a blind U.S. senator from Oklahoma who was an isolationist and opposed the United States’ entry into World War II.

Wrathall leaves the implicit impression that Vidal’s interest in politics stemmed from his tenure as his grandfather’s aide in Washington, D.C. Thanks to him, Vidal doubtlessly learned a lot about Capitol Hill, but unfortunately, Wrathall glosses over the details.

Vidal finished his first novel, Williwaw, at the age of 19, writing it while convalescing in a U.S. army hospital after having contracted a tropical disease in the Pacific theatre.

He thinks he was destined to be a novelist. “You don’t decide to be a writer,” says Vidal. “You are one.”

Vidal’s second book, The City and the Pillar, the first American novel to deal explicitly with homosexuality, was published in 1948. Finding it morally objectionable, the New York Times‘ daily reviewer announced he would henceforth boycott Vidal.

Hollywood handsome, Vidal was a gay man in an era when homosexuality was not even tolerated, yet he never bothered to conceal it. For decades, he and his partner, Howard Austin, a Jew, lived together. Yet Vidal suggests that their relationship was asexual and that he had numerous affairs, not all of them with men. Vidal was promiscuous, arguing that sex destroys relationships.

Only once in the film is Vidal raked over the coals for being a homosexual, and this occurs in a testy TV debate in which conservative ideologue William Buckley, the publisher of The National Review, branded Vidal a “queer” after he had called Buckley a “crypto-Nazi.”

After being blacklisted by the New York Times, Vidal went west, working as a contract scriptwriter in Los Angeles. Among the movies he was associated with were Ben Hur, Is Paris Burning? and Suddenly, Last Summer. Like many talented writers, Vidal did not take Hollywood seriously. Certainly, he appears to have earned more money cranking out plays for television. He used his earnings to buy a spectacular white-washed, seaside villa in Italy, where he wrote political novels such as Burr, Lincoln and Empire.

Thinking he could make a difference, and having been inspired by John F. Kennedy’s presidential campaign of 1960, Vidal ran for a New York state seat in the U.S. House of Representatives. He lost. In 1982, he tried electoral politics yet again, running in California for a U.S. Senate seat. His opponent, Jerry Brown, won by a considerable margin.

Wrathall devotes a considerable portion of the film to Vidal’s political views, which veer to the left. Vidal blames Kennedy for having enmeshed the United States in the Vietnam war and claims he did “practically nothing” during his “disastrous” presidency. He dismisses Ronald Reagan as an adept “cue card reader” and lambastes George W. Bush as a “god damn fool.”

In his most inflammatory observations, he claims that his country has become “an empire of the most predatory kind,” asserts that the United States brought the Sept. 11, 2001 terrorist attacks upon itself (“We had that coming”), denounces the war on terrorism and argues that American neo-conservatives are the “enemies of the republic.”

Vidal is mercilessly harsh on the U.S. media, claiming that newspaper ownership is controlled by a few companies, and that newspapers create a “false reality” and teach “conformity.”

Apart from offering such sexy sound bites, Wrathall does remarkably little to offer a viewer a rigorous explanation of Vidal’s ideology.

Nor does he really explain Vidal’s apparent antipathy to Israel. Vidal says that New York Jewish intellectuals were once his allies, but voices regret that they have “defected to the right” and aligned themselves with antisemites. Presumably, he is referring to, among others, Commentary editor Norman Podhoretz. But have all Jewish intellectuals drifted rightward? Hardly.

That’s the chief problem with this otherwise accomplished film. Too many generalizations are made, often at the expense of the nuanced inconvenient truth.