From the antisemitic and fascist movement of Charles Maurras’ Action Francais, through the collaborationist wartime Vichy and the Algérie Française eras, reactionary thought has a long history in twentieth century France. It was one of the mainstays of a current which vigorously opposed the revolutionary and Republican traditions.

Since the disaster of World War II, in which the country collapsed under the Nazi offensive, though, this reactionary strand has been on the defensive, confined to the fringes of the extreme Right.

But is France forgetting this sordid past?

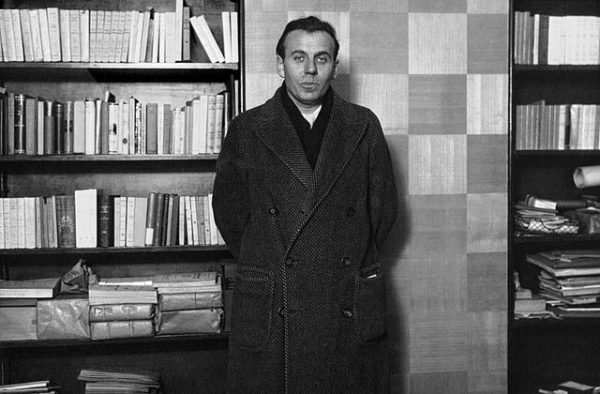

A recent scandal in France concerned the author Louis-Ferdinand Céline. Late last year, Antoine Gallimard, head of the French publishing house founded in 1919, received a letter from Frédéric Potier, head of the French government’s inter-ministerial delegation against racism and antisemitism, asking the company to justify its decision to publish an edition of three ferociously antisemitic pamphlets by him.

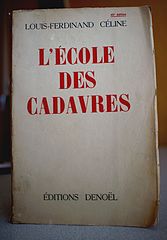

Bagatelles Pour un Massacre, L’école des Cadavers, and Les Beaux Draps were written and released between 1937 and 1941. They called for the murder of the country’s Jews, even before France fell to the Nazis in 1940. They have never since been reissued in France.

After France’s defeat, Céline became so extreme that he attacked Vichy for its lack of rigor in its pursuit of the Jews. He advocated killing every man, woman and child with machine guns. Vichy did eventually deport more than 75,000 Jews to the Auschwitz death camp.

He fled France for Germany after the Allied liberation and joined the remnants of the collaborationist government in its last redoubt, Sigmaringen Castle in Germany. He returned to France in 1951, when he was amnestied and died ten years later.

Criticism of the decision was swift and loud. When far-right writers, politicians, and comedians are convicted in French courts for incitement to hatred and antisemitism, they asked, why should Gallimard be permitted to reissue antisemitic diatribes?

On January 11, bowing to public pressure, the publisher reversed its position and suspended publication of the pamphlets.

All this followed another outrage, this one concerning Maurras.

The French government at first included his name in the 2018 edition of the National Commemorations, an annual project to mark the anniversaries of notable figures and events.

Since Maurras was born in 1868, he was listed.

There was swift, sharp fallout. Maurras was until the end of World War II “the most prominent anti-semite in France” and an enemy of liberal democracy,” according to Zeev Sternhell, an emeritus professor at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem and an expert on the history of French fascism.

Maurras was the intellectual leader of French “hard nationalism” until the end of the Vichy government, added Sternhell. “It was no accident that he had been sentenced to life in prison.”

On January 28, it was announced that the entire press run of the 2018 commemorative books would be recalled and reprinted without mention of Maurras.

France is struggling to maintain and protect its large Jewish population, the third largest in the world, which has been dwindling precipitously thanks to the wave of antisemitism that has gripped the country over the past decade.

This is certainly no way to reassure them.

Henry Srebrnik is a professor of political science at the University of Prince Edward Island.