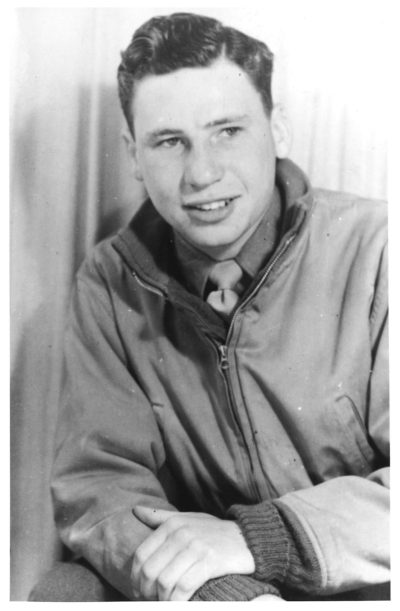

Five hundred thousand Jewish Americans, many of them the sons and daughters of immigrants, served in the U.S. armed forces during World War II. Ten thousand of them were women. Lisa Ades’ absorbing documentary, GI Jews: Jewish Americans In World War II, scheduled to be broadcast on the PBS network on April 11 at 10 p.m. (check local listings), examines their experiences through an array of personal stories.

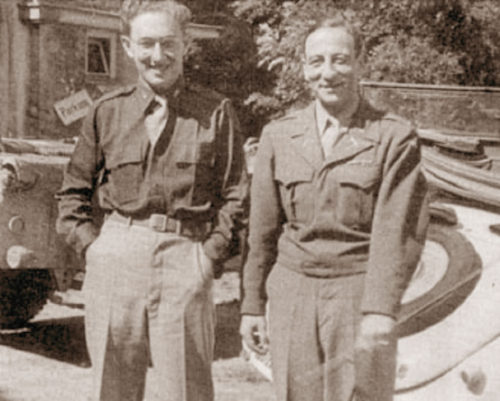

We hear from such luminaries as the diplomat Henry Kissinger, the filmmaker Mel Brooks and the television comedy writer Carl Reiner. We’re also told about the novelist J.D. Salinger and the baseball star Hank Greenberg. Most of all, we’re privy to the recollections of ordinary men and women who laid their lives on the line for their country.

Whether they enlisted or were drafted, Americans of the Jewish faith who joined the army, navy, merchant marine, air force or marines were motived by a strong sense of patriotism. To their disappointment, they discovered that antisemitism was as much present in the armed forces as it was in society at large.

Antisemitism was a malignancy that no self-respecting Jew in peacetime could ignore. It affected university admission policy, employment, housing, hotels and resorts. It was not the kind of vicious state-sponsored antisemitism found in Nazi Germany, but it left its impression on generations of American Jews who thought that the United States was a model of tolerance.

In fact, America was riven by racism. And while African Americans and Asians bore the brunt of it, Jews were hardly immune.

Jewish recruits who spent 16 weeks in basic training in bases around the nation encountered white Christian Americans who had never met a Jew and had been influenced by ageless antisemitic tropes and stereotypes. Since these encounters were not necessarily congenial, some Jews kept a very low profile. “I didn’t advertise the fact that I was a Jew,” says a woman.

Until America’s entry into the war, following the Japanese bombing of Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, the U.S. military was segregated by race, with African Americans serving in separate units. But with the influx of countless of Jews into the services, the religious issue surfaced, forcing the military to launch a campaign to combat prejudice. It worked, at least to some extent. Bigots could set aside their ill will toward minority groups when they were in the same foxhole as a Jew fighting the enemy, be it Germany or Japan.

Jewish servicemen were particularly at peril in Europe. The letter H on their dog tags placed them at risk if they were taken captive by German forces. Acutely aware of this potential problem, some American officers advised Jewish troops to dispense with their dog tags before going into battle. Whatever their decision, the opportunity to kill Germans usually fired up Jews. One Jewish bombardier daubed a blunt message on the bombs he expected to drop on Germany: “Hitler — a gift for you.”

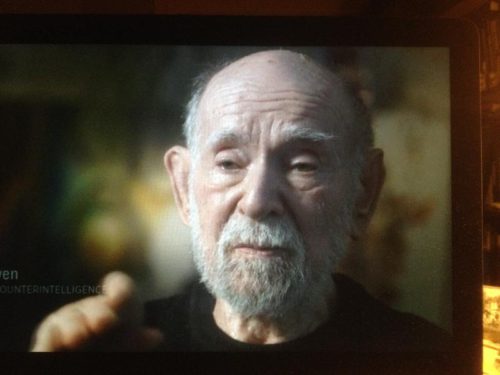

German Jews whose families had immigrated to the United States after the rise of Nazism in Germany hankered for revenge. “It was my great chance to get even,” says one man. As might be expected, the U.S. intelligence corps recruited Jews of German descent. Kissinger was one of them, as was Si Lewen, who would become a professional artist and illustrator.

Still other Jews served in the Pacific theater. Norman Mailer gathered material for his bestseller, The Naked and the Dead, there. Harry Corre was not so lucky. Along with 20,000 American troops captured by the Japanese, he was forced to participate in the deathly Bataan death march to a squalid prison camp.

On D-Day, in June 1944, Harold Baumgarten was one of 160,000 troops who took part in the decisive Allied invasion of Europe. The naval craft he was on was hit by German bullets, killing nine of the eleven soldiers who had boarded the vessel. He was wounded as he stormed German lines. “It was a horrible day, the longest day,” he recalls.

When Paris was liberated that summer, Maurice Paper looked for his relatives and found a few who had come out of hiding after the four-year German occupation of France.

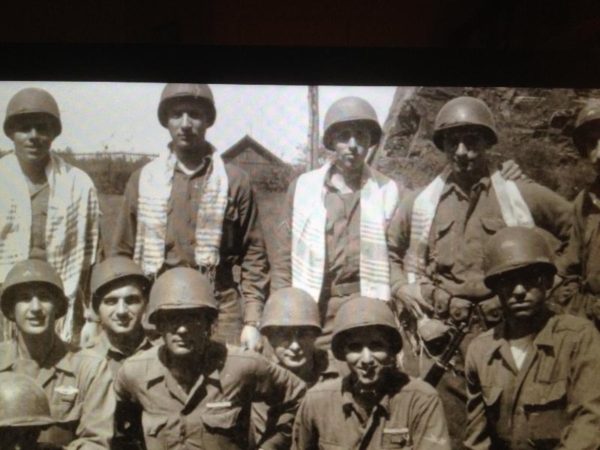

The first Jewish religious service broadcast from Germany since the Nazi era was aired from Aachen shortly after it was captured by the American army in the autumn of 1944. The service was conducted by a Jewish chaplain.

Toward the end of 1944, the Germans launched a last-gasp offensive during which 19,000 American troops were killed and 15,000 were captured. Some POWs were transported to a German camp, Stalag 9A, where the commander demanded the identities of Jewish soldiers. At the urging of an American Protestant clergyman, the men to pretend they were Jewish, thereby saving the lives of 200 Jews.

During the final months of the war, Allied forces stormed into several German concentration camps, including Mauthausen, and the revolting sights that greeted them left an indelible mark. Kissinger helped liberate a camp from which his grandmother had set off on a fatal death march.

As the film points out, Jewish servicemen returning to the United States after the war demanded equal rights. Some vets went to Israel as volunteers during the 1948 War of Independence. Still others involved themselves in the civil rights movement in the 1950s and 1960s.

The war was a turning point in their lives, as GI Jews suggests.