In 2010, Paul Kagame, president of Rwanda since 2000 and candidate of the ruling Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF), won a second term with 93 percent of the vote, in an election marred by repression, murder, and lack of credible competition.

Some potential opponents were disqualified or failed to enter the race, because they would have been charged with “divisionism.”

Article 54 of Rwanda’s 2003 constitution states that “political organizations are prohibited from basing themselves on race, ethnic group, tribe, clan, region, sex, religion or any other division which may give rise to discrimination.”

What is that all about? It’s part of an attempt to rewrite the country’s bloody history.

On April 6, 1994 President Juvénal Habyarimana of Rwanda was returning from a summit in Tanzania when a surface-to-air missile shot his plane out of the sky over Rwanda’s capital city of Kigali. All on board were killed in the crash.

President Habyarimana, a Hutu, had run a totalitarian regime in Rwanda, which had excluded all Tutsis from participating. That changed on August 3, 1993, when Habyarimana signed the Arusha Accords, which would have weakened the Hutu hold on Rwanda and allowed Tutsis to participate in the government.

Eight months later he was dead.

Although it has never been determined who was truly responsible for the assassination, Hutu extremists in the National Republican Movement for Democracy and Development profited the most from Habyarimana’s death. Within 24 hours after the crash, they blamed the Tutsis for the assassination, and launched the slaughter.

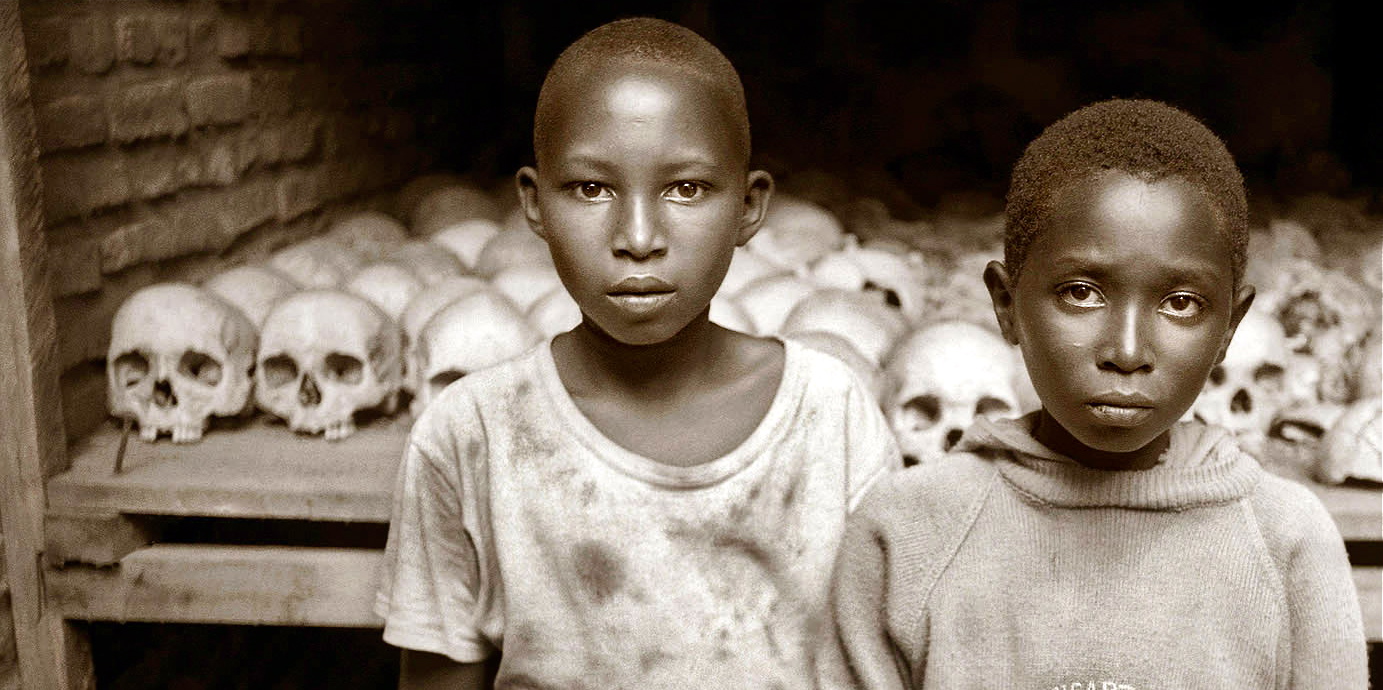

From April to July of 1994, upwards of perhaps one million Tutsi were massacred by Hutu-led gangs and the country’s army. It ended when Tutsi exiles in Uganda, organized in the RPF, invaded the country, marched into the capital of Kigali, and defeated the perpetrators of the genocide.

Some two million of the genocidaires, known as the Interahamwe, fled into the vast rain forests of the eastern Congo, from where they have periodically launched attacks into Rwanda.

Retaliation by the RPF government has precipitated a series of wars in the Congo that has led to the deaths of millions of people, but that litany of horrors is another story.

The Rwandan genocide was the largest mass killing of an identifiable ethnic group since the Holocaust, and in terms of numbers killed places it just behind the Ottoman massacres of Armenians during World War One. (Other mass murders, including Communist Pol Pot’s extermination of millions of fellow Cambodians in the 1970s, cannot quite be classified as genocides, since they were based on political ideology, not “race.”)

Of course, Africa has been the scene of numerous mass murders, including the aforementioned Congo. Probably the best-known recent example is the slaughter of black Africans by Arab Janjaweed in the Darfur region of Sudan. The killings began in 2003 and, while they have recently tapered off, some 500,000 people are dead, and Sudan’s president, Omar al-Bashir, has been indicted by the International Criminal Court on charges of genocide and crimes against humanity.

More recently, a fanatical movement of Islamists, Boko Haram, has been responsible for the deaths of thousands in northern Nigeria, while the Central African Republic is the scene of unspeakable horrors at the hands of a mostly Muslim coalition of rebels and bandits known as the Seleka. France recently warned that the country now stands “on the verge of genocide.” Burundi, the state just south of Rwanda, is in many ways a “mirror image” of its neighbour. It, too, has been the scene of Hutu-Tutsi brutality.

There, following a Hutu uprising against the Tutsi-dominated regime in 1972, mass killings of Hutu resulted in anywhere between 80,000 to 210,000 dead. In October 1993, a half year before the Rwandan genocide, Burundi’s first Hutu president was assassinated by Tutsi extremists. As a result of the murder, violence broke out between the two groups, and an estimated 50,000 to 100,000 people died within a year.

A 1996 UN report concluded that “acts of genocide against the Tutsi minority were committed in Burundi.”

In Rwanda, Hutu nationalists had come to power in the “Hutu rebellion” of 1959–1962, during the last years of Belgian colonial rule. They overthrew the traditional Tutsi kingdom and its ruling class, resulting in the death of around 20,000 Tutsi and the exile of another 200,000 to neighboring countries. Independence from Belgium in 1962 marked the establishment of a Hutu-led Rwandan government. The Tutsi remaining in Rwanda were excluded from political power.

The RPF was formed in 1985 by Tutsi nationalist exiles who demanded the right to return to their homeland and an end to social discrimination against the Tutsi in Rwanda. They attacked Rwanda from neighboring Uganda in 1990. Although the invasion failed, Hutu fear of losing power paved the way for mass murder four years later. Pro-genocide propaganda ran in newspapers, dominated public gatherings, and was broadcast across the country. Tutsi were referred to as “cockroaches.”

Since 1994, the RPF-led government has been dominated by a small clique of anglophone Tutsi who had been in exile in Uganda, and who blamed Belgium and France for having supported Hutu rule. (Although never ruled by Britain, Rwanda joined the Commonwealth in 2009.) They have made “divisionism” and references to “Hutu” and Tutsi” in public discourse a crime, as part of its “unification” policies designed to create a national identity. Offenders can be prosecuted, newspapers shut down, and political parties banned.

The government insists that all of the country’s citizens are simply “Rwandans” and has had the history books rewritten to stress the “harmony” of its pre-colonial past. This form of what the sociologist Stanley Cohen, in his book States of Denial, refers to as “social amnesia,” is an attempt to allow the country to separate itself from its horrific past.

This is not the first time, nor will it be the last, that politically constructed identities have been imposed on diverse societies.

According to this new historical discourse, prior to the arrival of, first the German, then Belgian, colonialists, the labels “Hutu” and “Tutsi” referred to wealth and social status, not “essentialist” ethnic groups, and hence they were fluid. Insofar as there was inequality between the royal court and ordinary Rwandans, both Hutu and Tutsi were equally victims of subjugation.

It was the Europeans, it is now claimed, who introduced the “Hamitic hypothesis” — the idea that the Tutsi were actually immigrants to Rwanda from Ethiopia, whereas the “Bantu” Hutu were indigenous to the region. The Europeans thus elevated the Tutsi as the supposedly “superior race,” breeding resentment among the Hutu.

This was demonstrated through rulings by the Belgians stating that “the government should endeavour to maintain and consolidate traditional cadres composed of the Tutsi ruling class, because of its important qualities, its undeniable intellectual superiority and its ruling potential.”

After 1934, the Belgian government introduced an identity card system, which identified each person as either a Hutu, Tutsi or Twa (a very minor ethnic group).

And by having defined the Tutsi as more recent arrivals, the colonialists also allowed Hutu nationalists to argue that the country should be restored to its “original” owners. With independence, Tutsi could thus be portrayed as a foreign minority who were enemies of the country.

So, according to this new government-sponsored version of history, the colonizers were the creators of ethnic dissension. Hence it was necessary to eliminate the colonial discourse about ethnic identity — which, by happy coincidence, also obscures the predominance of the minority Tutsi (now some 15 percent of Rwanda’s 12 million people) and allows them to run the state without official reference to that fact, even though everyone knows it!

Henry Srebrnik is a professor of political science at the University of Prince Edward Island.