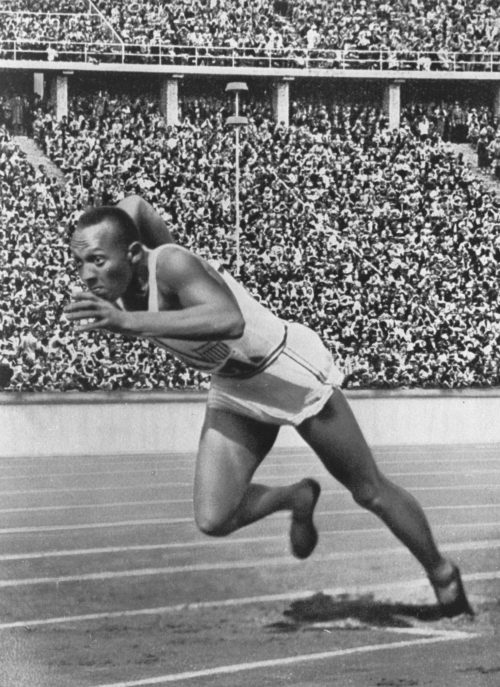

Stephen Hopkins’ workmanlike feature film, Race, pays homage to Jesse Owens, the African-American track and field star who, at the 1936 Olympic Games in Berlin, left his competitors in the dust and demolished the Nazi notion of Aryan racial superiority, much to the ire of Adolf Hitler and company.

But Race, which is now available on the Netflix streaming network, is more than a glowing portrait of a sports legend. It offers dramatic glimpses of the impassioned debate within the American Olympic Committee on whether the United States should send its athletes to Germany. And it captures the antisemitic spirit of a country in thrall to a fascist movement that marginalized and terrorized its Jewish community.

The movie, featuring a strong cast, gets underway as Owens (Stephan James) arrives at Ohio State University on a track scholarship. He gets his first taste of insidious Jim Crow racism on campus when white football players in the locker room object to his use of the showers.

Owens’ reputation as a stellar sprinter has proceeded him, but his coach, Lawrence Snyder (Jason Sudeikis), advises him there is room for improvement in his sprinting style.

At this juncture, the film segues to New York City, where activists brandishing anti-German placards stage a demonstration calling on the United States to boycott the upcoming Olympics in Germany. And at a meeting of the U.S. Olympic Committee, heated arguments break out. One faction claims that the Olympics will be prejudice-free and that two Jews already have been selected to be on the German team. Another faction expresses doubt that the Nazi Olympics will be inclusive.

Avery Brundage (Jeremy Irons), a committee member, is dispatched to Berlin to ascertain whether Germany will be true to Olympic ideals. As he’s driven into the city from the airport, he sees two antisemitic street signs: “Don’t buy from Jews” and “No Jews and dogs allowed.”

Brundage, in a meeting with Propaganda Minister Joseph Goebbels (Barnaby Metschhurat), lays out his demands. The United States will not participate in the games if Jews and blacks are excluded. “You’ve got to clean up your act,” he thunders. Goebbels, who’s depicted as a venal and extremely unpleasant person, says in German, “Jews are on their way out.”

Race pivots back to the United States as Owens competes at the Big Ten track meet in Anne Arbor, Michigan, in May 1935. In a spectacular and still unequalled feat, he breaks four world records in less than an hour.

With the Olympics only months away, Owens is pressured by the president of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People to skip the games. It’s important to strike “a powerful blow” against Nazi bigotry and to show solidarity with “oppressed people” in Germany, he says. The pep talk has an effect on Owens. “I don’t know if I can go to Berlin,” he tells Snyder. “If you don’t go, you’ll feel you made the biggest mistake of your life,” he counters persuasively.

In Berlin, the legendary German filmmaker Leni Riefenstahl (Carice van Houten) puts in the first of several appearances. Hard on the heels of her classic documentary, Triumph of the Will, she is making a film about the Olympics.

Owens, in an impressive scene, walks into the cavernous stadium, glances around and hears the thunderous sounds of “Sieg heil” as Hitler takes his seat. Regrettably, the sprinting and broad jump scenes, during which Owens wins the first of four gold medals, are wooden.

After winning the 100 meters event, Brundage approaches Owens. He wants him to meet Hitler. But the fuhrer has already left the stadium. “Do you think he would allow himself to be photographed with that?” Goebbels sneers.

In a remarkable show of sportsmanship in full view of tens of thousands of spectators, the German broad jumper and European champion Carl Luz Long (David Kross) gives Owens a bit of valuable advice as he gets ready for his final jump. Much to Goebbels’ disgust, they shake hands after Owens’ victory. Later, in his Olympic village room, Long denounces the Nazis. “I love my country, but it’s no secret my country is going insane,” he says in an astonishing confession, which may or may not be historically true.

When Owens triumphs in the 200 meter sprint, Goebbels, the arch villain of Race, reacts with shock. As for Hitler, he leaves abruptly as the crowd exultantly shouts, “Owens, Owens, Owens.”

To his credit, Hopkins includes an important footnote in the movie — the disgraceful decision by the United States to bench the only Jews on the track team, Marty Glickman and Sam Stoller. As a result of German pressure, they were prevented from competing in the 400 meter relay. Owens and Ralph Metcalfe, another African American sprinter, replaced them. Owens protested, but to no avail.

Such was the temper of the times in the 1930s. Hopkins distills this atmosphere with aplomb.