Is bipartisan support for Israel in the U.S. Congress slipping? This appears to be the case, judging by a series of recent events.

A festive ceremony in Jerusalem on May 14 marking Israel’s 70th anniversary of statehood and the opening of the American embassy in Jerusalem attracted a small delegation of Republicans from the Senate and the House of Representatives, but not a single member of the Democratic Party.

It’s not clear whether invitations were even issued to Democrats, or whether Democratic lawmakers decided to pass.

On the same day as these festivities unfolded, the Israeli embassy in Washington, D.C. celebrated these milestones with a big bash. Again, Democrats were conspicuous by their absence. Representatives Ted Deutsch (Florida) and Nita Lowey (New York) were invited, but could not attend due to previous engagements. Representative Jerrold Nadler (New York) told a journalist he had not been invited.

It has yet to be determined whether the Israeli embassy invited Democrats other than Deutsch, Lowey and Nadler. But at the end of the day, Democrats were no where to be seen at the embassy party, raising troubling questions whether Israel’s heretofore solid bipartisan base in Congress is at risk of crumbling.

On May 16, Democratic Senator Dianne Feinstein (California) upset Israel by expressing disappointment that the U.S. ambassador at the United Nations, Nikki Haley, had vetoed a United Nations Security Council resolution calling for an investigation into the deaths of 60 Palestinians attempting to breach the border fence between the Gaza Strip and Israel.

“I’m deeply disappointed by ambassador Haley’s decision to block a UN inquiry,” said Feinstein, sharply parting company with Israel, which opposes such an inquiry. “Without question there should be an independent investigation when the lives of so many are lost.”

Another Democratic senator, Bernie Sanders (Vermont), who challenged Hillary Clinton for the Democratic Party presidential nomination in 2016, also raised eyebrows in Israeli government circles by posting a video on social media demanding an end to Israel’s 11-year blockade of Gaza, its withdrawal from the West Bank and “the right (of Palestinians) to return to their former homes inside Israel.”

Feinstein and Sanders joined 10 other Democratic senators in writing a letter to U.S. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo urging him to take steps to improve the deteriorating situation in Gaza, populated by two million Palestinians, 70 percent of whom are refugees or descendants of refugees.

The rift between the right-wing government of Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu and the Democratic Party has been simmering for the past three years.

In March 2015, much to the annoyance of the Democratic president, Barack Obama, Netanyahu accepted an invitation from the Republican Speaker of Congress, John Boehner, to address Congress on the Iran nuclear agreement, which would be ratified several months later by Iran and the six major powers. Netanyahu, in concert with the vast majority of Republicans, denounced the accord, which the Obama administration staunchly supported and promoted.

It was not the first disagreement between Netanyahu and Obama. Throughout Obama’s eight-year term, they were often at loggerheads over Israel’s occupation of the West Bank and Palestinian statehood.

The new Republican president, Donald Trump, has been far more in sync with Netanyahu than Obama. Last December, he recognized Jerusalem as Israel’s capital, much to the outrage of the Palestinians and Arab states. And last month, he withdrew from the Iran nuclear accord, as Netanyahu had strongly urged.

As a result, Republicans generally tend to be more supportive of Israel than Democrats, particularly left-of-center Democrats like Sanders.

According to a Pew Research Centre survey conducted last year, 74 percent of Republicans sympathize with the Palestinians over Israel, compared to 33 percent for Democrats.

Yair Lapid, the leader of the middle-of-the-road Yesh Atid Party, warned last week that Netanyahu is “dangerously” aligning Israel with conservative and evangelical factions of the Republican Party, thereby widening the gap between Israel and the Democratic Party.

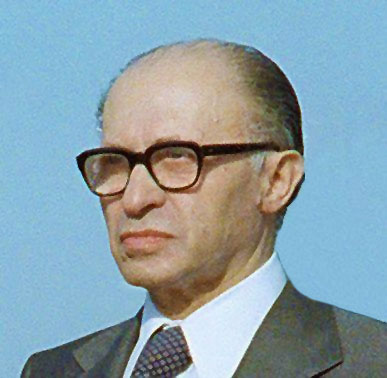

In fact, it was one of Netanyahu’s predecessors, Menachem Begin, the first Likud Party prime minister of Israel, who devised the strategy of forming alliances with evangelical Christians. Netanyahu has simply taken it to the next level.

Ron Dermer, Israel’s ambassador to the United States, concedes that “devout Christians” have become the “backbone” of support for Israel in the United States. Indeed, David Friedman, the U.S. ambassador to Israel, said recently that they back Israel with “much greater fervor and devotion than many in the Jewish community.”

Dermer, however, insists that Israel is intent on maintaining bipartisan support for Israel among Republicans and Democrats.

Mort Fridman, the president of the American Israel Public Affairs Committee, known as AIPAC, says that bipartisanship for Israel is critical. As he said recently, “The progressive narrative for Israel is just as compelling as the conservative one.”

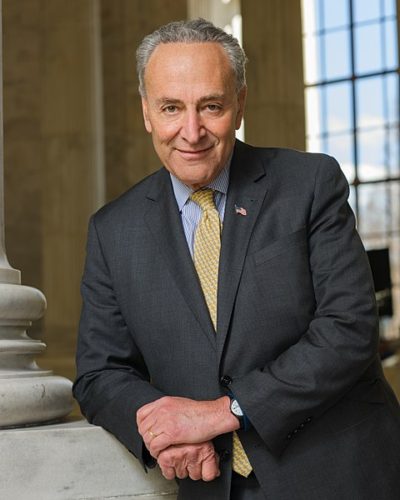

Bipartisanship is absolutely essential, says Senator Chuck Schumer (New York), the Democratic minority leader in the Senate. Speaking to the Israeli American Council at the Library of Congress last month, Schumer said, “If we don’t have bipartisan support for Israel, if Israel becomes the domain of one party or another, Israel will lose.”

The chairman of Israeli American Council, Adam Milstein, totally agrees with Schumer. “The U.S.-Israel relationship is — and must always be — rooted in bipartisanship.”

The former U.S. ambassador to Israel, Dan Shapiro, has cautioned Israel to be wary of “burning bridges” with the Democratic Party.

“Israeli leaders may find it difficult to resist the temptation to ride this wave, embracing one aside in partisan U.S. political battles, as when Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu arranged his speech to Congress against the Iran deal solely with the Republican congressional leadership,” he wrote in a piece in the Atlantic in January. “But that approach comes at the cost of alienating even longtime allies across the aisle, and when the next crisis inevitably hits, Israel’s leaders may regret having burned those bridges.”

In closing, Shapiro warned Israeli leaders not to throw in their lot with the Republicans alone. This approach would be short-sighted and counter-productive, he said.

To say the very least.