In the spring of 1933, a Los Angeles Police Department captain submitted a report indicating that “considerable quantities” of antisemitic literature had been found littering the streets of the city’s downtown core.

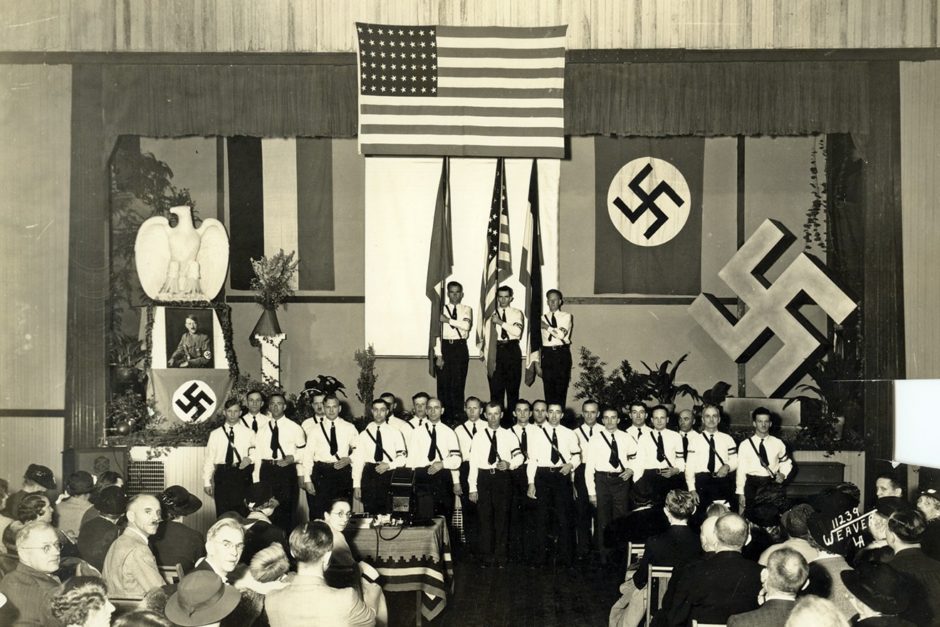

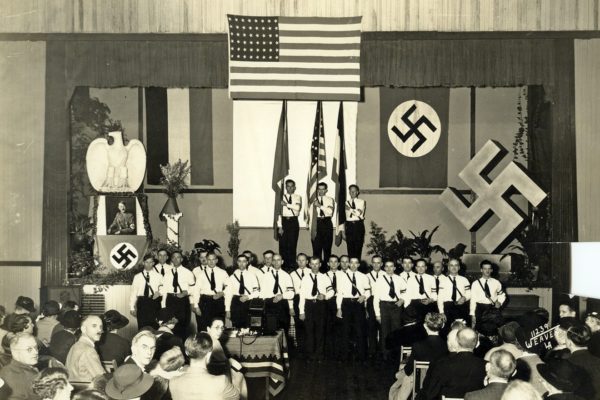

A new group, Friends of the New Germany, was believed to be behind this sudden burst of Nazi propaganda. An undercover detective was assigned to keep an eye on it, and he reported that its first two meetings took place at Deutsches Haus, a German American community center housing a German-style restaurant, Alt Heidelberg, and a bookshop, Aryan Bookstore.

As the detective soon discovered, the antisemitic leaflets had been imported from Germany. What he did not know was that the Friends of the New Germany, which would be renamed the German American Bund, was modelled after Germany’s ruling party and was regarded by the Nazi leadership in Berlin as the official Nazi party in the United States.

Responding to the emergence of overt Nazism in Los Angeles, Jewish community leaders joined forces with the executives of the motion picture industry to form the Los Angeles Jewish Community Committee (LAJCC), the first Jewish anti-Nazi organization in the country. Similar defence groups were established in nine American cities ranging from New York and Chicago to Seattle and Portland.

LAJCC’s aims were two-fold: to join interfaith coalitions combating religious intolerance and to gather information about the upsurge of Nazism in Los Angeles and beyond. Partnering with the Anti-Defamation League, the American Jewish Committee and non-sectarian groups such as the American Legion, LAJCC sent its data to the Los Angeles Police Department, the U.S. Congress, the FBI and the Justice Department in the hope of exposing and quashing homegrown Nazis.

Laura B. Rosenzweig, an American historian based in California, has written a fascinating and readable book about this intriguing footnote in Los Angeles’ history. Hollywood Spies: The Undercover Surveillance of Nazis in Los Angeles, published by New York University Press, charts the progress of the LAJCC from its founding in 1934 to its dissolution in 1945.

As she points out, the LAJCC emerged at a time when Germany was conducting a secret campaign to transplant National Socialism to the United States, where antisemitism was at its historic peak. This was an economically-fraught period when about two-thirds of Americans believed that Jews had too much power and posed a threat to American security, according to opinion polls.

Antisemitic demagogues like Gerald Winrod and Father Charles Coughlin exploited these ethnocentric feelings to the hilt.

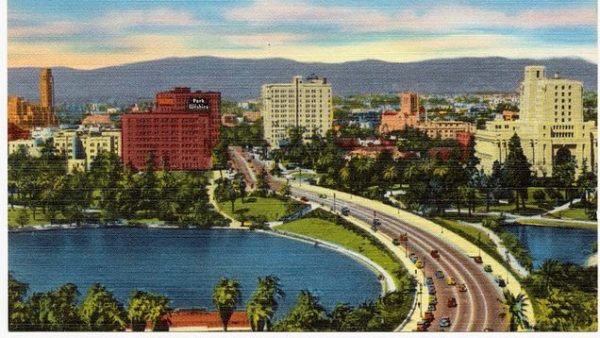

California was especially susceptible to the wave of right-wing nativism. During the first three decades of the 20th century, millions of lower middle-class Americans flocked to California to start their lives anew. These so-called “second starters,” whose social and economic status was uncertain, were receptive to reactionaries who blamed Jews, among others, for the problems that ailed America. Los Angeles, in particular, was filled with “second starters.” As a result, the City of Angels was a hotbed of fascism.

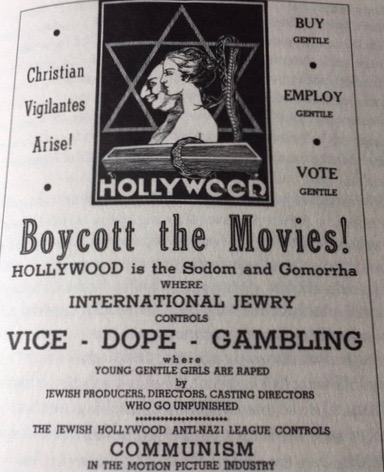

The climate of the times was such that in 1935 an antisemitic flyer, the Proclamation, was found stuffed inside a Sunday edition of The Los Angeles Times, the biggest newspaper in the city. Calling for a boycott of Jewish businesses, it claimed that Jews were a “nation within a nation” intent on subverting the “American way of life.” The Proclamation was also left on front lawns and slipped under the doors of Jewish shops in Los Angeles, San Diego and Santa Barbara.

The LAJCC hired two informants, Neil Ness and Charles Slocombe, to track down the authors of the Proclamation. To no one’s surprise, they traced it back to Friends of New Germany.

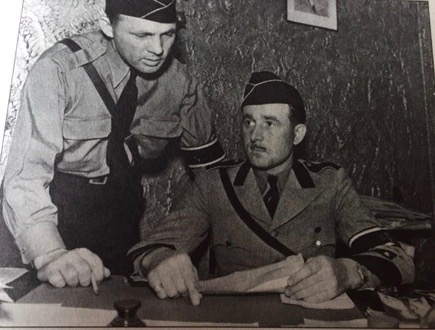

Ness, a super spy, managed to infiltrate Friends of New Germany, now known as the German American Bund. Its west coast leader, Herman Schwinn, was so impressed by Ness that he appointed him editor of its house organ. Ness documented the relationship between the Bund and the Nazi regime and confirmed that Germany was the primary source of the Bund’s antisemitic and pro-Nazi literature, which was smuggled past U.S. Customs officials.

Slocombe burrowed his way into the Silver Shirts, deemed by the LAJCC as one of the most dangerous antisemitic groups in the United States. Founded by William Dudley Pelley, a former Hollywood screenwriter, the Silver Shirts sought to create “a Gentile government against the Jews.”

The LAJCC was founded by Mendel Silverberg, a high-powered attorney, and Leon Lewis, the first executive secretary of the Anti-Defamation League of B’nai Brith. They made sure to distance the LAJCC from the Jewish left so as to protect its members’ “tenuous status as ‘Americans.'”

From the outset, Hollywood studio executives like Jack Warner and Irving Thalberg provided the LAJCC with funds, leadership and strategic political support, though they were not personally involved in its day-to-day affairs.

When the occasion called for it, Hollywood writers, actors, producers and directors lent their support. Rosenzweig says that prominent Jews like Warner and Thalberg had been under attack for years by Protestant and Catholic groups, both of which claimed that the Hollywood film industry was undermining the morals of ordinary Americans.

Working discreetly, the LAJCC compiled some victories. It convinced the Immigration and Naturalization Service to investigate Schwinn, a German whose U.S. citizenship was eventually revoked. Schwinn, however, was neither arrested nor deported to Germany. Leopold McLaglen, a British-born fascist, was deported for espionage. But Leslie Fry, a paid German propaganda agent, was never arrested because she never broke any law.

In 1938, the LAJCC submitted a brief, Summary Report on Activities of Nazi Groups and their Allies in Southern California, to the Dies Committee, which would be reborn as the House Un-American Activities Committee in the U.S. Congress. The Dies Committee issued a report exposing American Nazis, but then, in an abrupt U-turn, its arch conservative chairman, Martin Dies of Texas, betrayed the LAJCC by writing a magazine series alleging Communist infiltration of the Hollywood movie industry.

Shortly afterwards, the LAJCC set up its own press agency, the News Research Service, whose sole task was to combat Nazism in the United States. The News Research Service published News Letter, a weekly intelligence report on Nazi fifth-columnists. It was run by Joe Roos, a former newspaper man and scriptwriter who had gone undercover to investigate Friends of New Germany. Rosenzweig says that newspapers and magazines regularly used its information in their coverage of American Nazis. Walter Winchell, probably the most widely read syndicated columnist in the 1930s, was perhaps its most influential subscriber.

The Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor marked the end of the LAJCC’s undercover surveillance of Nazi groups in Los Angeles. It also signalled the demise of the News Letter. The FBI raided German American Bund cells across the country. Seventy six Bund leaders, including Schwinn, were arrested and jailed as “dangerous aliens.”

The day after Pearl Harbor, the United States declared war on Germany. “Nazis were now the enemy of all Americans,” says Rosenzweig. “With federal agents and military authorities on the job, the LAJCC’s covert anti-Nazi resistance operations were no longer necessary.”

Although antisemitic organizations in Los Angeles continued to function during the war, incidents of organized antisemitism virtually disappeared. The News Research Service, though, remained busy after Pearl Harbor, with federal law enforcement officials and military intelligence agents calling on its services.

During the first half of the 1940s, the LAJCC reinvented itself as a civil rights movement, marshalling the expertise it had amassed fighting Nazism to promote racial equality in American society, says Rosenzweig.