Whether Islamic State was merely a flash in the pan or an organization still capable of regenerating itself after devastating battlefield defeats, it has already cast a dark shadow.

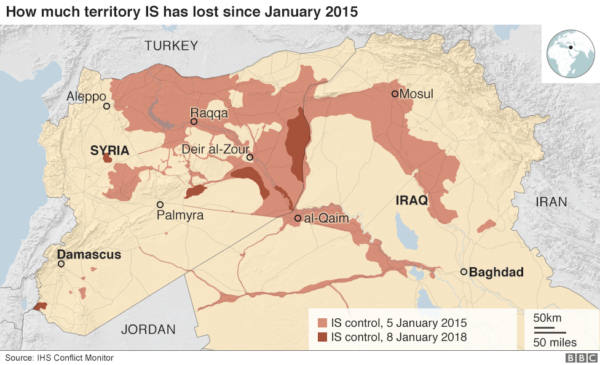

Spreading fear and terrorism throughout the Middle East and Europe following its extensive territorial conquests in Iraq and Syria, IS established a caliphate in 2014, the high point of its ascendancy. But since 2016, it has been on a losing streak, having been militarily defeated by Iraqi, Syrian, Iranian, Lebanese, Turkish, Russian and American forces.

Its dramatic rise and fall is meticulously examined down to the last detail by Ahmed S. Hashim in The Caliphate at War: Operational Realities and Innovations of the Islamic State, published by Oxford University Press.

At the outset, he compares IS to the ancient Assyrians, “whose army, system of totalitarian rule and infliction of terror as state policy was the scourge of the Middle East between 2500 and 605 BC.”

IS emerged as Sunni insurgents in Iraq launched a nation-wide rebellion against the U.S. occupying army. From the outset, IS capitalized on sectarianism to promote itself as a defender of Sunnis, whose ambition was to regain power after the fall of Iraqi President Saddam Hussein. The Shias, by contrast, sought to obtain power.

To many Iraqis, be they Sunni or Shia, the US invasion of Iraq was designed to keep it weak for Israel’s benefit. Al Qaeda, which was involved in the insurrection, assiduously promoted this view.

By Hashim’s count, five distinct groups waged war on the Americans: Iraqis who had served Saddam Hussein’s Sunni Baathist regime, nationalists, tribal Arabs, local Islamists and foreign fighters. From the outset, he adds, senior Iraqi army officers joined the rebellion, having been enraged at the loss of their jobs, incomes and pensions.

IS morphed into a comparatively potent organization under the leadership of Abu Musab al-Zarqawi, a Jordanian who welcomed foreign fighters to its ranks. But after his death at the hands of the Americans in 2006, the insurrection unravelled and disintegrated. IS’s battle against U.S. forces was stymied by, among other factors, informers and American firepower. By 2008, Hashim notes, U.S.-led coalition and local security forces had killed 2,000 IS personnel and taken 9,000 prisoners. By 2010, 34 of its 42 senior leaders had been wiped out.

IS’s success on the battlefield from 2013 onwards was primarily a function of the incompetence of Kurdish peshmerga forces and the Iraqi army, which was riven by sectarianism, poor motivation, corruption and a deep gulf between foot soldiers and officers.

The U.S. withdrawal from Iraq in 2011 signalled the end of IS’s decline. “The Iraqi security forces simply did not have the training, flexibility and energy to plan and execute fast-paced operations against the jihadists of the kind the Americans were capable of conducting, ” writes Hashim. In short order, IS conquered a string of Iraqi cities, including Mosul, the second-largest city; Tikrit, Saddam Hussein’s childhood home, and Ramadi, the capital of Anbar province.

As the conflict intensified, Baghdadi took advantage of the chaos in Syria to send men and materiel there. This was an ironic turn of events, since Syrian President Bashar al-Assad had permitted foreign jihadists to travel to Iraq via Syria.

From 2013 onward, IS worked to gain ideological supremacy over the Sunni insurgency. Contrary to some accounts, Zarqawi was not a Palestinian Arab. Nor was he a political philosopher or a polished scholar. His objective was to eradicate the ills afflicting the umma, the Muslim community at large. His enemies were the “crusaders” in the West, primarily the United States and Israel.

Zarqawi resorted to anti-Western and antisemitic calumnies. But, as Hashim adds, “scurrilous antisemitic and anti-Israel outpourings were common among the jihadists and the nationalist and Baathist elements” of the Sunni insurgency.

Zarqawi and his Iraqi successor, Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, reserved their greatest animus for the Shias, the most insidious enemy of Islam. They had forsaken Islam and had acted as a Trojan horse that the enemies of Islam could exploit to their advantage. From 2011 to 2014, in particular, IS wreaked physical and psychological havoc on the Shia population. Beyond marginalizing and killing Shias, both Zarqawi and Baghdadi considered Christians and Jews as legitimate targets. Zarqawi justified suicide bombings as the most effective operational method for jihadists.

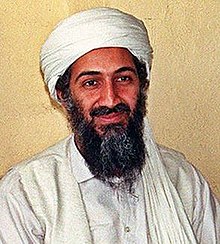

Al Qaeda leader Osama bin Laden had predicted that an Islamic super state would replace the “artificial” Arab states that had arisen following the breakup of the Ottoman empire in 1918. Nonetheless, Al Qaeda refused to accept Baghdadi’s declaration of a caliphate. IS thus broke away from Al Qaeda and became an independent entity. Al Qaeda’s negative attitude stemmed not from ideological antipathy toward the aspirational goal of a caliphate, but largely from the fact that it was not feasible.

Still, the proclamation of the caliphate, a momentous event, resonated with a large number of Muslims. According to Hashim, “statehood” turned out to be a “monumental blunder,” since it allowed its enemies to target its assets.

During its heyday, IS was awash in money, its funding derived from a variety of sources: kidnapping, human trafficking, extortion, taxation, confiscation of property, sale of antiquities and sales of oil and gas. In 2015, its annal budget was $2 billion.

Hashim believes that IS was welcomed in many places initially because it replaced a despised government that had provided little or no services or security. IS, having brought law and order, entrenched itself in the daily lives of its inhabitants, especially in the fields of justice, social service, education, culture and health. In keeping with its ideological orientation, it abolished school courses in science, history, geography and physical education.

By the end of 2015, its state-building efforts began crumbling as living conditions deteriorated in areas under its control. Much to Baghdadi’s probable distress, services collapsed, prices soared and diseases broke out.

The caliphate has been in free fall since then.

Hashim argues that IS might have fared better had it consolidated control over captured areas instead of engaging in territorial expansion. IS could then have conserved its resources, rationalized its borders and defended them more easily, he claims.

But because IS has proven to be extremely resilient, he is not writing it off just yet. While it has steadily lost its caliphate, its full defeat is still far off. “The world should be prepared for the next phase of its evolution,” he warns ominously.