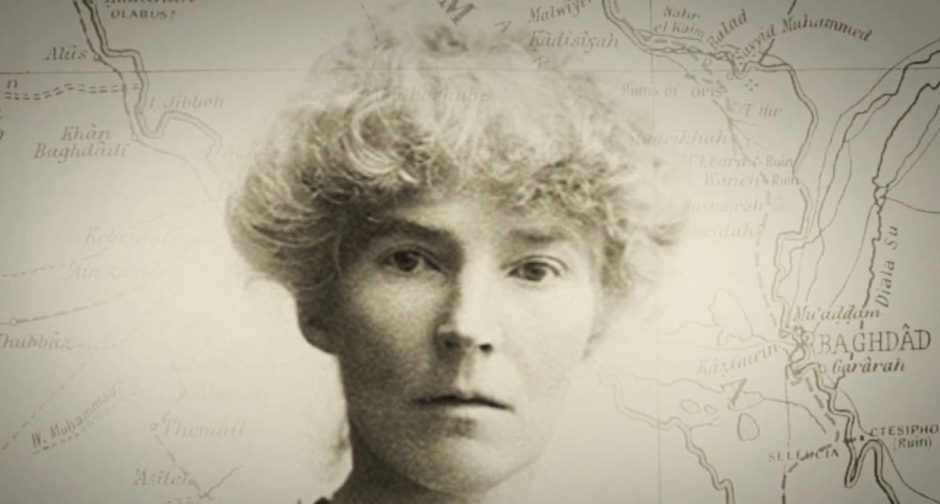

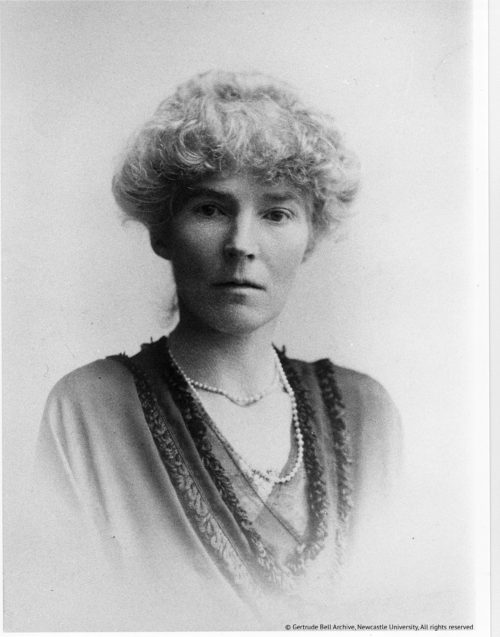

Long before the emancipation of women in Western societies, Gertrude Bell led the way forward as an historian, political analyst, administrator, archeologist, writer and photographer. She was surely was one of the most influential females of the 20th century.

T.E. Lawrence, known as Lawrence of Arabia, hailed her as “a wonderful person.”

D. G. Hogarth, another one of her contemporaries, wrote, “No woman in recent time has combined her qualities — her taste for arduous and dangerous adventure with her scientific interest and knowledge, her competence in archeology and art, her distinguished literary gift, her sympathy for all sorts and condition of men, her political insight and appreciation of human values, her masculine vigor, hard common sense and practical efficiency — all tempered by feminine charm and a most romantic spirit.”

More than any other person in the British colonial service in the Middle East, Bell was instrumental in the creation of Iraq, where she died and was buried.

Bell left behind a trove of correspondence, which forms the core of Letters from Baghdad, a PBS documentary by Zeva Oelbaum and Sabine Krayenbuhl scheduled to be broadcast on December 11 at 9 p.m. (check local listings).

This alluring film, narrated by the British actress Tilda Swinton in sonorous tones, is composed of readings, heretofore unseen file footage and dramatizations.

Born in 1868 into a wealthy, upper-crust family, Bell was an intelligent, self-confident and ambitious person. At Oxford, where she was one of the very few female students, she studied modern history.

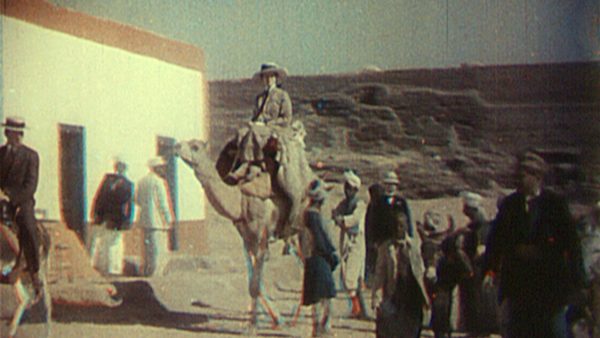

In 1892, she visited the Middle East for the first time, spending much of her time in Persia, whose exotic sights and sounds awed her. She was no ordinary traveller. Her uncle, the British ambassador in Tehran, arranged her itinerary. Bell learned Farsi and fell in love with a Briton who died after a brief illness.

As the filmmakers state, Bell’s destiny was fixed by her Persian adventure, which inspired her to write her first book, Persian Pictures. She was determined to return to the region that had captured her imagination. “I don’t expect to be in England in the future, inshallah,” she mused in one of her letters. “I have seldom felt the ancient world come so close.”

True to her sentiments, Bell returned to the Middle East, exploring the magnificent ruins of Palmyra in Syria. During the course of her travels, she met Lawrence. “An interesting boy,” she commented. In another letter, she wrote, “I have become a person in Syria.” But as far as the Ottoman Turks were concerned, Bell was a spy rather than just a curious traveller.

Bell, a keen and assiduous observer, wrote Syria: The Desert and the Sown upon returning to Britain. By now, she was considered one of Britain’s foremost specialists on Arab history and culture.

In 1913, she led a caravan of explorers into the Arabian peninsula, which was torn by tribal conflicts. Her beloved father, Hugh, financed the journey. One wonders whether her wanderlust could have been satisfied without his assistance.

On the eve of World War I, she met Charles Doughty-Wylie, a diplomat and soldier who would be the love of her life. He was killed in 1915 in Gallipoli. Once again, death claimed a lover.

In 1915, she began working for the Arab Bureau in Cairo under the direction of Sir Gilbert Clayton, the head of British military intelligence in Egypt. Bell wrangled the position thanks to family connections. Bell’s fluency in Arabic and knowledge of Arab tribal politics enabled her to land a job as an assistant political officer in Baghdad in 1917 under Britain’s high commissioner, Sir Percy Cox. Eventually, Cox would appoint her Oriental secretary.

“I think an Arab state in Mesopotamia is a possibility,” she presciently wrote.

As part of her duties, Bell cultivated minority groups in Baghdad, including the 80,000-strong Jewish community. “No doubt they’ll be a great power here some day,” she predicted, not knowing that the rise of Zionism and Arab nationalism would doom Iraqi Jews three decades later.

Unlike most of her British contemporaries, Bell supported Arab rule in what would be Iraq. But she believed the Sunnis, a minority in a Shi’a-dominated country, should be in charge of its affairs. On a more global level, she sympathized with the Arabs’ desire for independence across the length and breadth of the Middle East.

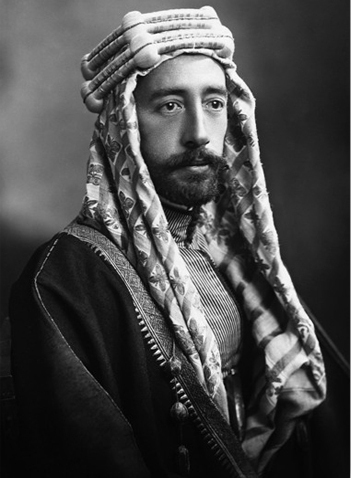

Bell played a pivotal role in the selection of Faisal, a Hashemite figure who had been forced to relinquish his throne in Syria, as the first king of Iraq. They formed a special bond, but ultimately, they had a falling out, and her influence waned. Nonetheless, she was under the impression she had the “love” and “confidence” of the Iraqi people.

In her final years in Iraq, Bell was the director of the department of antiquities. In this capacity, she was one of the founders of the Iraqi Museum, an institution housing some of Iraq’s finest archeological relics.

Bell died on July 12, 1926 from an overdose of sleeping pills. To this day, the jury is still out as to whether she committed suicide.