Reconstruction, one of the most complex, turbulent and divisive eras in American history, left a legacy of hope and terror that still haunts the United States.

Extending from approximately 1865 to 1877, it raised a mountain of contentious racial, social, political and economic issues as Northerners and Southerners grappled with the outcome of the 1861-1865 Civil War. Some were resolved, but still others festered.

Reconstruction: America After The Civil War, an ambitious and illuminating four-part series on the PBS television network starting on April 9 at 9 p.m., examines this pivotal period and its aftermath. It’s hosted by the African-American historian Henry Louis Gates Jr.. Commentaries are provided by well-regarded specialists ranging from Eric Foner to Edward Ayres.

With the 1863 Emancipation Proclamation, President Abraham Lincoln, a Republican, freed about four million slaves in the Confederacy, an amalgamation of Southern states which had seceded from the Union primarily over the inflammatory issue of slavery. Freed slaves enlisted in the Northern army, joining tens of thousands of blacks who had already done so. By all accounts, their contribution to the Union’s victory was significant.

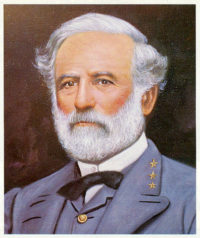

In practical terms, slavery ended when the commander of Confederate forces, General Robert E. Lee, surrendered to the commanding general of the Union Army of the Potomac, Ulysses S. Grant, at Appomattox, Virginia, on April 9, 1865. Lee’s capitulation set into motion events that, for better or worse, altered America profoundly.

Reconstruction was supposed to readmit breakaway states into the Union, rebuild the shattered South and grant liberated slaves the civil rights — citizenship, the right to work, vote, hold office, own land and acquire an education — that white Americans enjoyed and took for granted. Resentful white southerners, though having been defeated on the battlefield, rejected the democratic norm that blacks and whites should be treated equally.

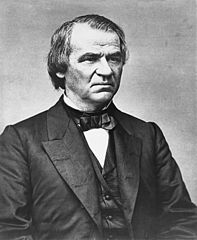

By Gates’ estimation, Lincoln’s successor, Andrew Johnson — a Southerner and a Democrat — tilted toward the South, effectively giving whites a free hand to subjugate blacks and ordering black farmers to return lands they had seized from white planters in the wake of the war.

No sooner had the war ended than Mississippi became the first Southern state to pass the “black codes,” regulations that marginalized and oppressed blacks. Violence perpetrated against blacks by former slaveholders and the Ku Klux Klan, which was created in Tennessee in 1866, worsened the situation. And in the spirit of national reconciliation, former Southern Democratic congressman who had served the Confederacy were permitted to take back their seats in Congress.

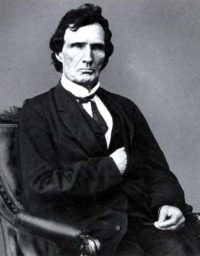

Radical Republicans like Thaddeus Stevens, who clamored for real change and clashed with Johnson, were instrumental in the passage of the 1866 Civil Rights Act, the first of its kind.

But in the South, anti-black riots broke out in Memphis and New Orleans, causing multiple deaths. As a result of these riots, Congress enacted the 14th constitutional amendment granting citizenship to African Americans. Recalcitrant Southern states refused to ratify the historic amendment, prompting Congress to give black men the right to vote and to hold office.

These edicts, opposed by Southerners but enforced by the U.S. army, ignited a sense of optimism in the African-American community. “We live in a new world,” exulted the black abolitionist Frederick Douglass. Yet, as he spoke, Southern white gangs terrorized black voters.

Despite the vociferous white backlash, African-American politicians were elected to Southern legislative assemblies. By the late 1860s, blacks held most of the seats in South Carolina’s assembly. Blacks, too, opened businesses and filled important public posts.

Black upward mobility, however, aroused indignation and anger in the South, spawning a counter-revolution. The Ku Klux Klan expanded, violence increased and white supremacist ideas proliferated. Amid these developments, support for Reconstruction declined in the Republican Party and in the North.

So-called “redemption” movements, advocating a return to the old retrogressive ways, emerged in the South as U.S. President Ulysses S. Grant promised to withdraw federal troops from Southern states. Grant’s successor, Rutherford Hayes, the former governor of Ohio who had been a Union general, pledged to end Reconstruction. In the meantime, Southern Democrats, who opposed key aspects of Reconstruction, regained control of their states, even as civil rights laws remained on the books.

These progressive laws were struck down in the 1870s and 1880s as segregationist Jim Crow regulations were phased in. During the 1890s, Southern states rewrote their constitutions, disenfranchising African-Americans by means of poll taxes and voter suppression tactics, all with the acquiescence of the North.

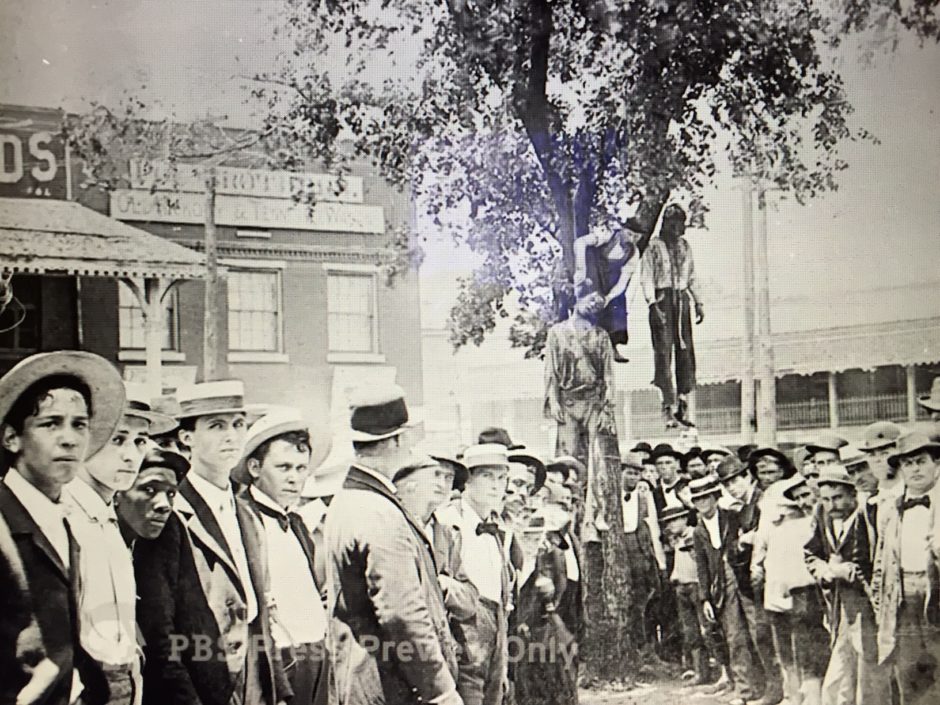

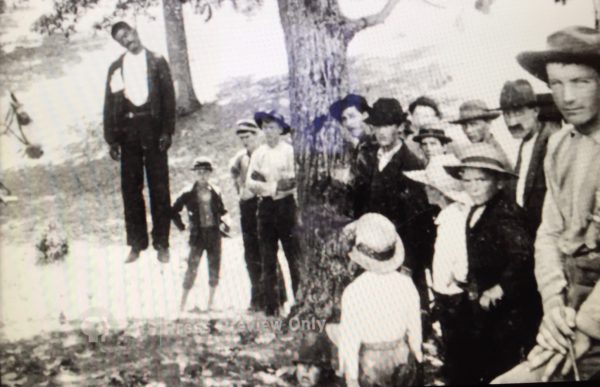

In this reactionary climate, racist theories pronouncing the genetic inferiority of blacks abounded. Vigilante violence, culminating in lynchings attended by respectable white citizens, was normalized. By one estimate, 3,400 blacks were lynched between the 1890s and the 1920s. Lynchings were widely regarded by whites as an instrument of control and were usually resorted to after a white woman accused a black man of disrespectful behavior or worse.

During this dark period, the nadir of black-white race relations in the United States, conservative African-American leaders like Booker T. Washington were hailed as role models in white elite circles. Washington believed that, in exchange for accepting white political rule, blacks should be given every opportunity to lift themselves up through education and economic independence.

The U.S. Supreme Court’s verdict in the Plessy vs. Ferguson case in 1896 led to the enshrinement of the racist “separate but equal” principle in American life and signalled the complete overthrow of Reconstruction. By the first decade of the 20th century, African-American politicians had been banished from Congress. Twenty five years would elapse before they were allowed to return.

As one commentator correctly says, Reconstruction aroused great expectations, achieved enormous advances and resulted in ignominious retreats.

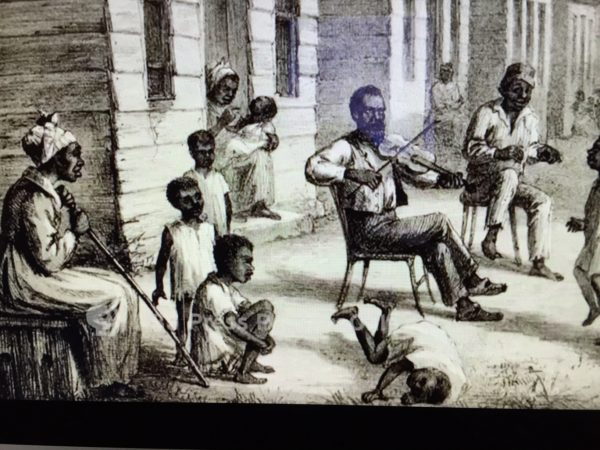

Having restored the status quo ante, minus slavery, Southern segregationists could now boast that white supremacy had triumphed. Monuments of Confederate heroes, an affront of blacks, cropped up all over the South, and school texts were rewritten to reflect the “Lost Cause” narrative that the Confederacy had been a just and noble undertaking and that slavery had been a benevolent phenomenon.

As overt racism spread its tentacles throughout the country, popular culture reinforced white supremacist ideas. Stereotypical images of African-Americans burst into mainstream prominence, while minstrelsy and “coon songs” became all the rage.

W.E.B. Dubois, the first African-American recipient of a Harvard University PhD, a founder of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, and author of the classic, The Souls of Black Folk, toiled to construct a positive image of blacks. But in the first half of 20th century America, he fought an uphill battle.

The Birth of a Nation, a silent feature film, romanticized the Old South and the Confederacy and gave impetus to the rebirth of the Ku Klux Klan. Such was the temper of the times that U.S. President Woodrow Wilson, a Southerner and a white supremacist, invited the director to screen his movie at the White House.

Decades would elapse before race relations in the United States took a turn for the better.

Yet, as Gates sagely observes, the dynamics and elements of inequality still afflict America, and Reconstruction remains an unfinished project in a nation struggling to be a genuine multiracial society.