Israeli voters have spoken loudly and clearly and essentially have opted for the status quo — more of the same from their longtime prime minister, Benjamin Netanyahu.

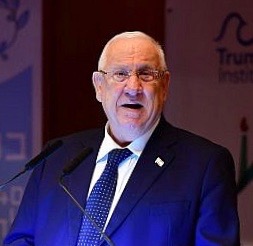

Netanyahu’s right-wing Likud Party, which has been in power for the past decade, won 35 Knesset seats in the April 9 general election, as many as Benny Gantz’s centrist Blue and White Party. But within a few weeks, if not earlier, President Reuven Rivlin is widely expected to invite Netanyahu rather than Gantz to form Israel’s next government.

Rivlin will turn to Netanyahu because right-of-center parties in Israel account for 65 of the Knesset’s 120 seats and thus have a greater chance of forming new governments.

In all likelihood, Likud will cobble together a coalition consisting of two religious parties — Shas and United Torah Judaism, the third and fourth largest parties — the centrist-right Kulanu Party and the far-right Union of Right-Wing Parties, all of which have a total of 60 parliamentary seats.

If Avigdor Liberman’s five-seat Yisrael Beytenu Party joins the coalition, Netanyahu will have 65 seats at his disposal. Liberman, the former defence minister, resigned last November, less than 24 hours after yet another ceasefire between Israel and Hamas went into effect. Liberman vehemently opposed the truce, saying it was a capitulation to terror.

Assuming that Liberman returns to cabinet, Netanyahu will have 42 days to establish a government. He should be able to pull it off and coast to his fifth term in office, surpassing David Ben-Gurion’s record for political longevity.

Pundits were less than certain that Netanyahu could overcome the challenge posed by Gantz and his two partners, Yair Lapid and Moshe Ya’alon. Netanyahu was confident he would prevail. When he launched his reelection campaign back in December, calling attention to his “great achievements” in security, the economy and infrastructure, he declared, “We will win.”

Netanyahu won his first election in 1996, defeating Labor Party candidate Shimon Peres by an extremely slim margin. He was ousted three years later by Peres’ successor, Ehud Barak, who went down to defeat to Ariel Sharon in 2001, during the first phase of the second Palestinian uprising. This bloody rebellion, which exacted a high toll on Israelis and on Palestinians in the West Bank and the Gaza Strip, pushed the Israeli electorate still further to the right, a process that really began after the 1967 Six Day War.

During his premiership, Sharon appointed Netanyahu as finance minister and foreign minister. With Sharon’s departure from the Likud, Netanyahu seized control of the party. In the 2009 election, Likud finished in second place, winning 26 seats but lagging behind the new, short-lived centrist Kadima Party, headed by Tzipi Livni, a former Likud member. Peres, then Israel’s president, asked Livni to form a government. Unable to do so, Livni dropped out, handing Netanyahu the opportunity to become prime minister once again.

In this month’s election, Netanyahu achieved the best result for Likud in years, falling only three seats short of Sharon’s record. Netanyahu’s achievement is a telling commentary on the state of politics in Israel today because his base was unaffected by Attorney General Avichai Mandelblit’s dramatic announcement in February to indict him on charges of bribery, fraud and breach of trust.

Netanyahu archly dismissed the corruption charges as a witch hunt and claimed they were politically inspired by the left to discredit him. Observers speculated that some of his supporters would grow disillusioned and abandon him, but this prediction did not pan out in the slightest. Nor were his admirers moved by subsequent reports that Netanyahu had benefited financially from a deal by Germany to sell submarines to Egypt, the first Arab country to sign a peace treaty with Israel.

Likud voters were basically satisfied with Netanyahu’s performance as a strong leader of the nation, citing his stewardship of the economy, his containment of Hamas, Hezbollah and Iran, his hardline approach to the Palestinians in the West Bank, and his support of Jewish settlements beyond the Green Line.

Likudniks also applauded his success in forging cordial relations with such important countries as Russia, China and Brazil, reaching out to Sunni Muslim nations like Qatar and the United Arab Emirates, reestablishing diplomatic relations with several predominantly Muslim African states, and, of course, forming mutually beneficial relationships with two key world leaders, U.S. President Donald Trump and Russian President Vladimir Putin.

Trump, having recognized Jerusalem as Israel’s capital, transferred the American embassy to Jerusalem. Much to Netanyahu’s satisfaction, Trump also pulled out of the Iran nuclear agreement, recognized Israel’s sovereignty over the Golan Heights, designated Iran’s Revolutionary Guards as a terrorist organization, ordered the closure of the PLO mission in Washington, D.C., and withdrew U.S. funding to the United Nations agency that serves the humanitarian needs of Palestinian refugees in the Middle East.

Netanyahu cultivated Putin because of Russia’s unsurpassed influential in Syria, an Arab nation that has been mired in a civil war since 2011. Much to Israel’s concern, the Syrian regime of President Bashar-al Assad has allowed Iran and pro-Iranian Shi’a militias to entrench themselves militarily on the Syrian side of the Golan and has permitted Hezbollah to transport weapons overland to its bases in Lebanon.

The Israeli air force has launched multiple attacks on Iranian — and Syrian — military sites in Syria, but Israel has had to coordinate its bombing raids with Russia by means of a deconfliction agreement that requires constant adjustments and regular meetings between Netanyahu and Putin. In this respect, Israel and Russia have not always been on the same page. In general, however, Netanyahu has managed the Russian file quite adeptly.

One can safely assume that Netanyahu will hew to the same foreign policy in the future.

With Russia’s tacit acquiescence, he will focus on degrading Iran’s military presence in Syria, a position that most Israelis endorse.

With the approval of the United States, he will place strict limits on Palestinian national aspirations in the West Bank, refusing to countenance the creation of an independent Palestinian state with East Jerusalem as its capital. Rejecting the land-for-peace formula, Netanyahu will offer the Palestinians limited autonomy, economic cooperation and peace for peace, while expanding Jewish settlements. A day before the election, tellingly enough, a Defence Ministry committee approved the construction of 3,600 new housing units in the West Bank.

And as promised in the last days of the election campaign, Netanyahu may well try to extend sovereignty over Israeli settlements in the West Bank, a strategy that will dash the possibility of a viable two-state solution.

The Trump administration most likely will back Netanyahu. Testifying before a Senate sub-committee on April 10, U.S. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo refused to reaffirm American support for Palestinian statehood. “Ultimately, the Israelis and the Palestinians will decide how to resolve this,” he said in a comment that must have been balm to Netanyahu’s ears.

As usual, Netanyahu will tread cautiously in confronting Hamas, which has ruled Gaza since 2007 and which has been subjected to an Israeli and Egyptian siege since then. Netanyahu went to war with Hamas in 2012 and in 2014, but he has no desire to embroil Israel in yet another war with Hamas.

Netanyahu will continue courting Sunni Arab states that fear Iran, the preeminent Shia’a power in the region. But these countries will not establish formal ties with Israel unless the Palestinian question is finally settled.

In a nutshell, Netanyahu faces serious challenges and golden opportunities as he prepares to rule Israel for another four years.