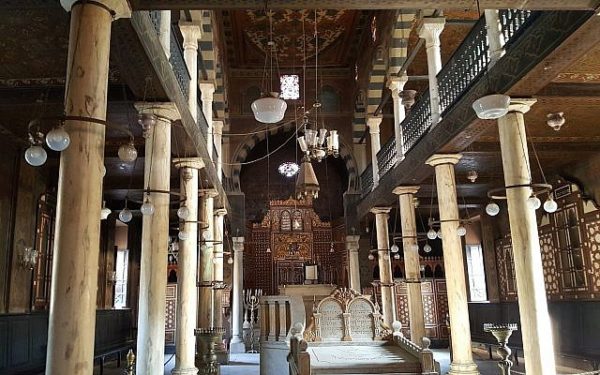

By the end of the 19th century, the venerable Ben Ezra synagogue in Cairo was falling apart and was in dire need of repair. During the restoration, workmen stumbled upon a massive cache of mouldering documents in the dusty attic ranging from the sacred to the mundane.

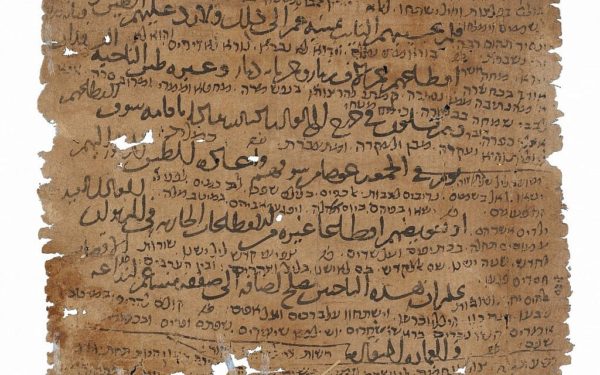

For approximately 1,000 years, the attic had been a repository, or Geniza, of discarded letters, fragments of religious texts, bills, contracts, Egyptian government decrees and the like. They were composed in such languages as Arabic, Aramaic, Hebrew, Judaic Arabic, Judaic Spanish and Judaic German (Yiddish) and written on vellum, paper, papyrus and cloth.

More or less undisturbed for centuries, these documents, numbering in the vicinity of 500,000 and comprising the largest and most diverse collection of medieval manuscripts in the world, offered an astonishing and intimate insight into a Jewish community that flourished in Cairo between the 10th and 12th centuries, when Egypt’s capital was a cosmopolitan city at the crossroads of the global economy.

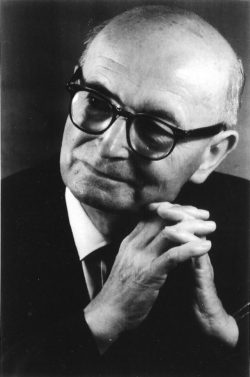

In 1896, Solomon Schechter, a Romanian-born scholar from Cambridge University in Britain, had the unique fortune of systematically examining this rare treasure trove. Amid clouds of ancient dust, flying insects and suffocating heat, he discovered one of the great finds of the 19th century.

Scholars and travellers since the 18th century had ventured into the Geniza, but Schechter was the first person to fully grasp its historic importance.

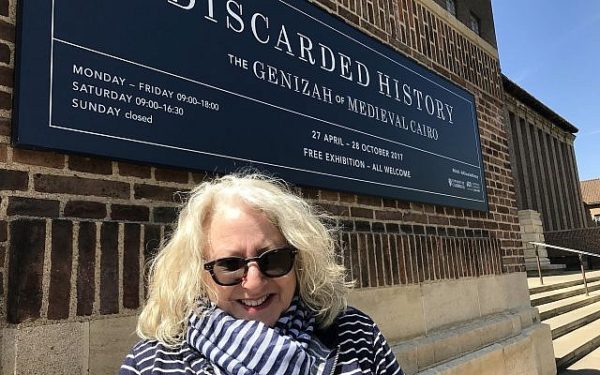

Michelle Paymar, a Canadian filmmaker, delves into Schechter’s odyssey in her erudite and entertaining documentary, From Cairo to the Cloud: The World of the Cairo Geniza, which is currently making the rounds of movie festivals in the United States and Canada.

Paymar tells her story in straight-forward journalistic fashion and supplements her fast-moving narrative with helpful comments from a panoply of Israeli, American, European and Arab specialists in the Geniza.

Schechter, of course, is at the center of it all.

An observant Jew and Cambridge’s only Jewish faculty member, he was a lecturer in talmudics and rabbinics. Two of his friends, the Scottish Presbyterian sisters Agnes Lewis and Margaret Gibson, showed him ancient Hebrew manuscripts they had bought from a dealer during a trip to Cairo. They told him the manuscripts had been retrieved from the Geniza.

Transfixed by their purchases, he decided it would be worth his while to visit the Geniza. Schechter’s friend, the Cambridge Hebrew scholar Charles Taylor, provided him with sufficient funds to travel to Cairo, which had once been called Fustat.

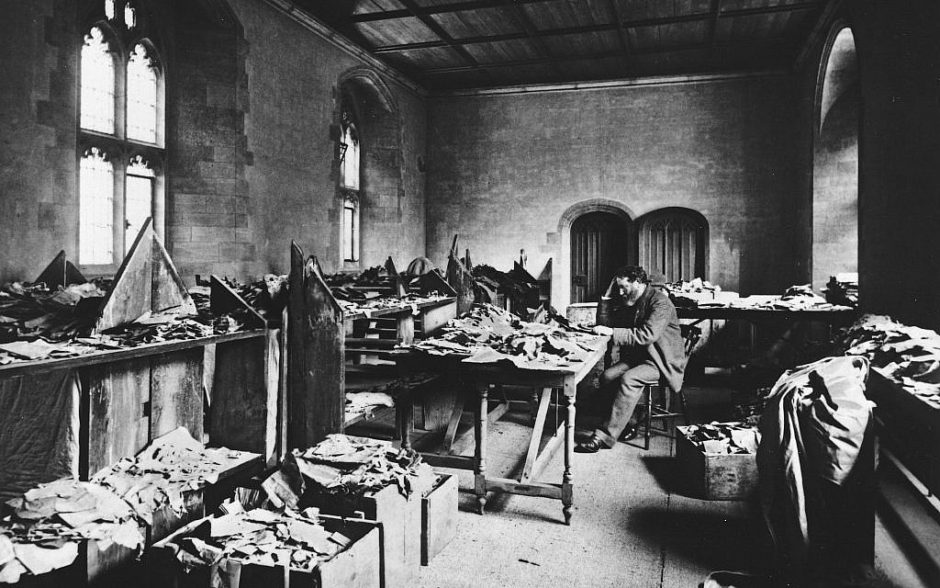

Schechter, having developed a good relationship with the chief rabbi of Cairo, was given permission to enter the Geniza and take what he wanted. Working under difficult conditions, he selected about 100,000 items. Paymar speculates that Schechter may have paid for them.

By all accounts, Cambridge is now in possession of about three-quarters of the Geniza documents, with the rest held by, among others, Oxford University, the Hebrew University, the Jewish Theological and the University of Pennsylvania.

Back in Cambridge, Schechter sifted through the material again, but it was left to an Israeli-American scholar, S.D. Goitein, to make use of it academically. He wrote A Mediterranean Society, a six-volume history of Egypt’s Jewish community that is still considered the standard work.

As for Schechter, he immigrated to the United States and became a founding father of the Conservative Judaic movement. He died in 1915.

In recent years, the documents Schechter found in the Geniza have been digitized and transferred to the Internet, making them accessible to an international audience.

One imagines that Schechter would have been pleased.