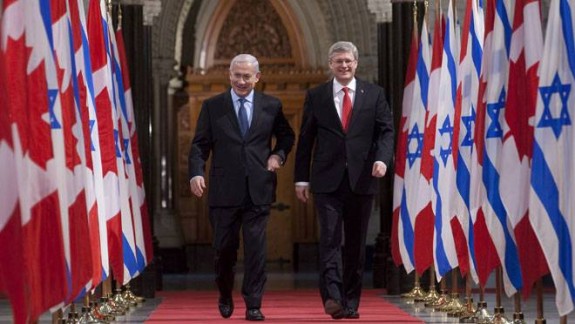

On Jan. 19, Prime Minister Stephen Harper will begin a four-day visit to Israel. He will be greeted like a rock star when he addresses the Knesset, Israel’s parliament, and becomes the first Canadian leader to do so.

“I (will be) pleased and proud to host the prime minister of Canada, a brave and true friend of Israel, at the Knesset,” Knesset Speaker Yuli Edelstein said last month.

Harper announced the decision when honored at a lavish “Negev Dinner” in Toronto in early December, sponsored by the Jewish National Fund and attended by 4,000 people.

Calling Israel “the light of freedom and democracy in what is otherwise a region of darkness,” Harper vowed that Canada would always be a friend. “We understand that the future of our country and of our shared civilization depends on the survival and thriving of that free and democratic homeland of the Jewish people in the Middle East.”

Rafael Barak, Israel’s ambassador to Canada, told Harper, “We are truly touched by your friendship and we admire your integrity.” And Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, in a videotaped greeting, told the guests that Harper “has stood up for Israel and he has stood up for the truth time and time again.”

Harper also paid tribute to the former Israeli prime minister, Ariel Sharon, who died this past Saturday. “A renowned military leader, Mr. Sharon pursued the security of Israel with unyielding determination that was recognized by friends and foes alike.”

Harper is unabashedly pro-Israel and makes no secret of it. In the United Nations and other international bodies, where Israel routinely comes under attack, Canada is arguably its most consistent defender. No country, not even the United States, has been as steadfast a supporter of the Jewish state as Canada has been since 2006, when Harper’s Conservative Party replaced the Liberals in office.

Harper cut off aid to the Palestinian Authority after Hamas won the 2006 Palestinian elections. That same year, he supported Israel in its war with Hezbollah in Lebanon. And Canada boycotted the UN’s 2009 Durban II anti-racism conference in South Africa because of its history of antisemitism and Israel-bashing.

In 2012, Ottawa cut off diplomatic ties with Iran, and it remains “deeply skeptical” of the recently-signed nuclear deal between Iran and the five members of the UN Security Council, plus Germany.

“Simply put, Iran has not earned the right to have the benefit of the doubt,” stated Foreign Minister John Baird, who recently announced that Toronto lawyer Vivian Bercovici will be Canada’s new ambassador to Israel. Baird added that Canada will continue to implement tough economic sanctions on the country.

In turn, Harper has earned the gratitude of a large sector of the Canadian Jewish community, in terms of electoral, financial and ideological support. He now has the almost unquestioning backing of most of the Orthodox Jewish community, the fraternal organization B’nai B’rith and other groups.

This is a remarkable achievement, for a number of reasons.

For most of the 20th century, Canada’s Jewish community was solidly Liberal — indeed, at various times even the New Democrats and their predecessor, the CCF, had more support among Jews than did the old Progressive Conservative Party. A Jewish Tory was an oddity.

As well, Harper’s political career began in the early 1990s within the Reform Party, the grassroots populist right-wing movement founded in Alberta, a province geographically and politically alien to most Canadian Jews, the vast majority of whom live in Montreal and Toronto.

Most Jews considered Reform as being, at the very least, antipathetic to Jewish concerns and values, if not (in the views of some) actually anti-Jewish. Its own political antecedent was the Social Credit Party, which had been led by evangelical Protestants who were at various times indeed openly antisemitic.

I lived in Calgary in 1990-1993, 1999-2001, 2003-2005, and 2007, as well as in most summers in between. Also, as an academic, I wrote articles about Reform. So I had a number of occasions to speak to and to interview Harper, who in 1993 had been elected the Reform MP for Calgary Southwest. I gained a very different impression of him from that of the Montreal and Toronto communities — I recall one of my cousins in Toronto at the time insisting that Harper was a “redneck antisemite.”

But the Reform Party eventually morphed into the Canadian Alliance and then the Conservative Party of Canada, with Harper at the helm. And a most remarkable thing happened: he gained the confidence of Canada’s Jewish community, thanks mainly to his loyalty to Israel during difficult times.

In the May 2011 federal election, an Ipsos Reid exit poll found that among Jewish voters, 52 percent voted Conservative, compared to 24 percent who voted Liberal and 16 percent who voted NDP.

This is an astounding turnaround, given the deep historic ties between the Jewish community and the Liberal Party. (Among those Canadian voters who identified as Muslims, only 12 percent voted Conservative.)

In the greater Toronto area riding of Thornhill, where 36.6 percent of the population is Jewish, the highest in Canada, Conservative Peter Kent beat the Liberal candidate, Karen Mock, by 61.3 percent to 23.6 percent. This had been a very safe Liberal seat between 1997 and 2008.

The Montreal riding of Mount Royal, with an electorate that is 36.3 percent Jewish, has arguably for decades been the most solid Liberal seat in the country. The Liberals have held the riding continuously since 1940. This was former Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau’s own seat between 1965 and 1984. He was a man Montreal’s Jews adored.

Yet former Liberal attorney-general and justice minister Irwin Cotler barely hung on to Mount Royal in the last election, beating Conservative challenger Saulie Zajdel with 41.4 percent of the vote to Zajdel’s 35.6 percent. Polling there demonstrated that a majority of Jews in the constituency voted Conservative. Cotler himself acknowledged that he didn’t get the support of most Jewish electors and only kept his seat thanks to the non-Jewish vote.

When Cotler had won the riding in a by-election in 1999, he received 91.9 percent of the votes cast; the Progressive Conservative candidate obtained less than four percent.

Harper’s political opponents, not wishing to step on Jewish toes, criticize his pro-Israel stance indirectly, bemoaning his abandonment of Canada’s “traditional” role of “even handedness” in its Middle East policy. Typical is an article, “ Canada’s Bitter, Small-minded Foreign Policy,” by Peter Jones of the University of Ottawa, in the Jan. 3, 2014 Toronto Globe and Mail.

“With issues such as Israel, Iran, religious freedom and more, Prime Minister Stephen Harper’s government is not interested in what Canada can actually do to help in any modest way,” he writes. “It is interested in what bluster and noise it can make to impress a key domestic constituency that it hopes to attract or retain as part of its ‘base.’ ”

Most Jews can read the subtext behind these words — the “domestic constituency” is, of course, the Jewish community. A lot of Canadians would prefer a tilt towards the Arab states, and particularly towards the Palestinian Authority.

Of course the Liberal “brand” is not dead yet. The new Liberal leader, Justin Trudeau, recently acquired the support of Stephen Bronfman as the party’s chief fundraiser.

Bronfman is a scion of the “first family” of Canadian Jewry — he is a grandson of Sam Bronfman, who built the Seagram liquor empire, making the family billionaires. Montreal’s Jews, with their fear of Quebec separatism, remain more loyal to the party of Pierre Trudeau than do their counterparts elsewhere.

But now it will be the Liberals, not the Conservatives, who will have to fight all the harder if they wish to regain the Jewish vote.

Henry Srebrnik is a professor of political science at the University of Prince Edward Island.

http://youtu.be/89L6A-n7SAM