At the height of his 40-year career at 60 Minutes, Mike Wallace was probably the most feared interviewer in the business. Hard as nails, with a no-nonsense style, he was a “rough boy,” as one of his many interviewees, Hollywood actor Kirk Douglas, said of him with a mixture of awe and annoyance.

Wallace, a reporter on the immensely popular CBS television network, is the subject of Avi Belkin’s riveting documentary, Mike Wallace Is Here, which opens in Canadian theatres on August 9. Hired by Don Hewitt, the creator of 60 Minutes, Wallace was an old school broadcast journalist who passionately believed his viewers had the right to know the unvarnished truth.

In quest of this lofty but often attainable objective, he researched his stories thoroughly and asked tough, politically incorrect questions that competitors might have avoided out of caution, tact or kindness. As a result, he angered some of the people he had grilled.

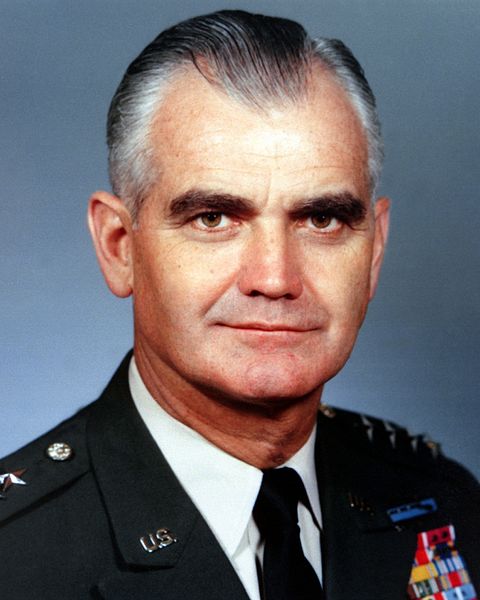

“You are a son of a bitch, the singer Barbra Streisand declared in a heated moment. “You’re a disgrace to American journalism,” fumed William Westmoreland, the four-star general who commanded U.S. troops in Vietnam and sued Wallace for libel.

Wallace even alienated colleagues. “Why are you sometimes such a prick?” Morley Safer wondered. As Belkin suggests, there was “a lot of temperament” in Wallace.

Despite his prickly personality and tendency to perform in front of the camera, Wallace was widely regarded as a talented, hard working journalist.

Belkin, an Israeli filmmaker, glosses over Wallace’s formative years, when he worked as an announcer and actor. And Belkin says precious little about his parents, Russian Jews who immigrated to the United States in the early 20th century.

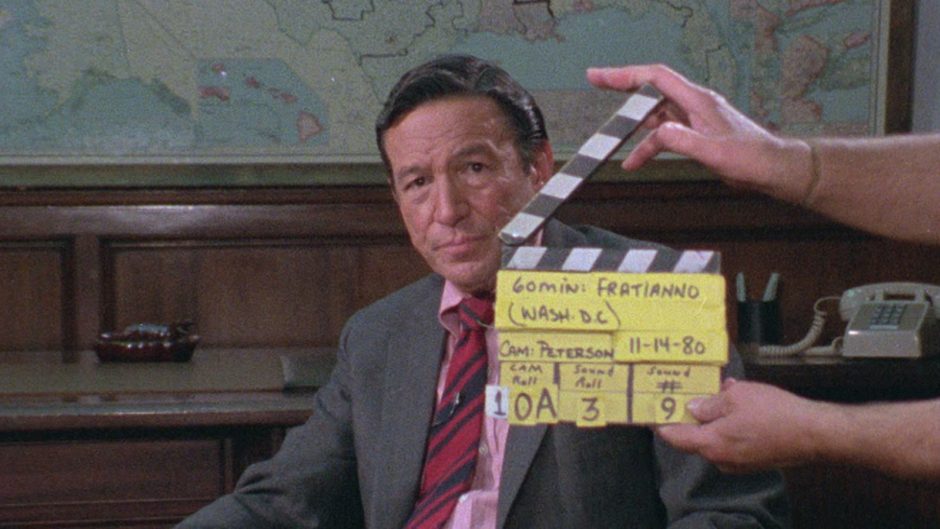

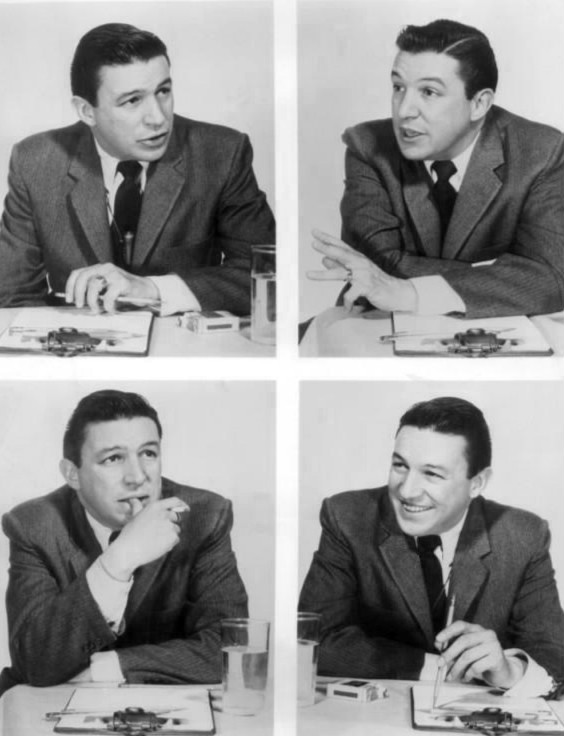

Wallace, who always had “something to prove,” developed his interrogative interview style on two hard-hitting TV shows, Nightbeat and The Mike Wallace Interview, in the mid 1950s. During this period, he branched into pitching cigarettes, cleaning products and cosmetics. “I hated it after a while,” he says.

A workaholic, he was married to his job, neglecting his wives and children.

A mountain climbing accident in Greece in 1962 claimed his 19-year-old son, Peter. Peter’s death, he muses, changed his life, encouraging him to become a “serious” reporter. After Wallace joined CBS, Hewitt poached him for 60 Minutes, which debuted in 1968 and which, Wallace admits, no one expected to last. Wallace covered Richard Nixon’s 1968 presidential campaign, the war in Vietnam and the Watergate scandal.

Nosy and insistent, Wallace brazenly asked Manuel Noriega, the deeply corrupt president of Panama whom the United States would eventually overthrow and imprison, how much he earned. Noriega smiled and shook his head in embarrassment or bewilderment.

Wallace also interviewed Ayatollah Khomenei, the first supreme leader of post-revolutionary Iran. Squatted on a carpet, like his interviewee, Wallace was instructed to submit his questions in advance. Being fiercely independent, he didn’t necessarily abide by these rules, visibly upsetting the glowering cleric. Khomenei accused Egyptian President Anwar Sadat of being a “traitor” after his historic rapprochement with Israel in 1979. Just two years later, Sadat was assassinated by Islamic fundamentalists.

In an interview with Russian President Vladimir Putin, Wallace expressed surprise by his fluency in English. But he displayed skepticism of Putin’s insistence that Russia is a democracy. In another clip from the archives, a real estate mogul named Donald Trump told Wallace he was not interested in entering politics.

Wallace got into hot water when Westmoreland, having accused him of a “scurrilous” attack on his character, sued CBS for $120 million. The case was settled out of court, but Westmoreland claims he won and was thereby vindicated.

Much to Wallace’s disappointment, CBS management was not prepared to protect him after he interviewed tobacco industry whistleblower Jeffrey Wigand, triggering a financially damaging lawsuit.

The most revealing moments in Belkin’s film occur when he confesses that he was plagued by depression and that he seriously contemplated suicide. Wallace looks vulnerable and frail in this segment.

In closing, an interviewer asks Wallace, who died in 2012 at the age of 93, how he would like to be remembered. The question rattles him momentarily, but he provides a reasonably plausible answer. He was tough but fair, a dogged muckraker who sought to expose the truth, warts and all.

That pretty well sums up Wallace.