The Six Day War, Israel’s greatest military victory over its Arab foes, opened up a can of worms, to put it in the vernacular.

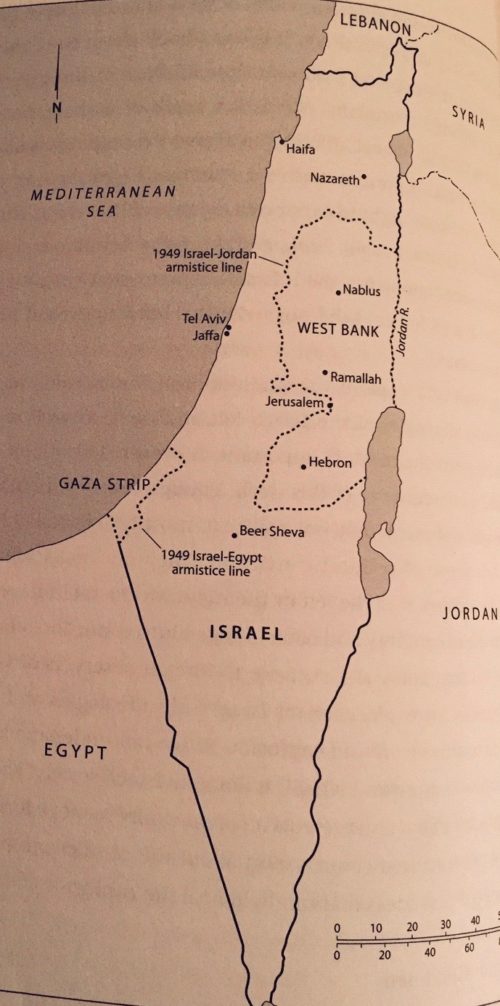

Israel’s conquest of the Golan Heights, Sinai Peninsula, Gaza Strip and West Bank in 1967 ignited a passionate debate about the future of the occupied territories. Today, with Israel having withdrawn from the Sinai and the Gaza and having annexed the Golan, this national conversation is focused on the West Bank.

Micah Goodman, in Catch-67: The Left, the Right, and the Legacy of the Six Day War (Yale University Press), cogently discusses this stormy, often poisonous debate, which essentially turns on where to draw Israel’s borders and whether Israel should acquiesce to Palestinian statehood.

The battle lines are clear.

The Israeli right claims that a withdrawal from the West Bank would leave the country shrunken, weakened, vulnerable and doomed to physical destruction, while the Israeli left contends that the occupation of the West Bank will leave Israel morally compromised, internationally isolated and facing demographic destruction.

Goodman reminds a reader that the current debate predates the Six Day War. As the 1948 War of Independence raged, David Ben-Gurion, the leader of the Yishuv, decided against conquering the West Bank. Since 1967, Israelis have been debating whether to withdraw from it.

A senior fellow at the Shalom Hartman Institute in Jerusalem, Goodman argues that this clash of ideas feeds into Israeli and Palestinian emotions. As he puts it, “The dominant emotion among Israelis is fear. Israelis fear the Palestinians. This fear is ancient, deep, and common to Israelis of all political stripes.”

By contrast, the Palestinians feel humiliated by the Israelis. “This humiliation inflames the existing feelings of hatred and anger, and creates a climate that breeds violence — violence that in turn heightens the Israelis’ sense of fear.”

In practical terms, he notes, these respective emotions block a possible diplomatic solution of Israel’s complex dispute with the Palestinians. Israelis who favor a Palestinian state generally insist that it must be demilitarized and that Israel must retain security control of the Jordan Valley. “But this demand is humiliating for the Palestinians,” says Goodman. “As a result, any agreement that would satisfy Israel’s security needs would be perceived as one that perpetuated Israel’s control over the Palestinians. Conversely, any agreement that would be acceptable to the Palestinians would be perceived as one that weakened Israel and exposed it to intolerant security threats.”

This is a prescription for political paralysis, of course. As Goodman observes, “When fear and humiliation collide, any possibility for political agreement goes out the window.”

He points out that Israel’s very existence is problematic to many Palestinians, who regard Israelis as Western invaders who implanted themselves on Palestinian soil. “The success of Zionism is a painful and living reminder to Muslims of their ongoing humiliation at the hands of Western civilization,” he says.

At this point, Goodman digresses, providing readers with what he describes as “a tale of two shifts.”

Religious right-wing Israelis tend to oppose partition, but as Goodman points out, the religious Zionist movement did not historically treat sovereignty over the whole Land of Israel as sacrosanct. Only since the Six Day War have religious, as well as secular, Zionists moved farther to the right.

The messianic philosophy of Rabbi Abraham Isaac Kook and his son, Rabbi Zvi Yehuda Kook, transformed the face of religious Zionism. However, some former rightists, such as Ehud Olmert and Tzipi Livni, renounced their vision of extending Israeli sovereignty over the entire Land of Israel, fearing that demography — the higher Arab birth rate — would turn Israel into a binational state.

Likewise, the leaders of the Israeli left, from Ben-Gurion on down, were for years very skeptical of reaching a lasting peace with the Arabs. But since the Six Day War, peace has become the object of their desire. “Leftists began to move away from the dream of a model socialist society, replacing it with the dream of peace,” says Goodman.

“These parallel processes occurred almost simultaneously,” he notes. “The new left and the new right collided with tremendous force, sparking the ideological conflict that unfolded after the Six Day War.”

In Goodman’s estimation, the first and second Palestinian uprisings had a marked impact on both sides.

The first intifada, which broke out in 1987, shattered the myth of the secular right that Israel’s occupation of the West Bank and Gaza could be sustained without fierce Palestinian resistance. The second intifada, which erupted in 2000, seven years after the Oslo peace accord was signed, “pulverized” the left.

Playing devil’s advocate, Goodman says, “From a security perspective, Israel must not withdraw from the territories, but from a demographic perspective, Israel must not remain there. If Israel withdraws, its area shrinks to indefensible proportions, but if it remains, its Jewish majority is in danger.”

Drawing a penetrating conclusion from this paradox, he writes, “The right is correct that a withdrawal from Judea and Samaria would endanger Israel. The left is correct that a continued (Israeli) presence in the territories would endanger Israel. The problem is that since everyone is correct, everyone is also incorrect — and the State of Israel is trapped in an impossible double bind.”

This, in effect, is Israel’s Catch-67.

There is a solution, he claims. Israelis must forge a “new reality” in which Israel would make peace by withdrawing from much of the West Bank, while the Palestinians would make peace by ceding the land beyond the 1948 lines.

In a tacit reference to Ben-Gurion and his associates, Goodman writes, “Israel’s founders had to sacrifice some of their dreams so that the country could come into being. Now, Israelis too must sacrifice some of their dreams so that Israel may continue to exist.”

Calling for a pragmatic approach, Goodman says, “If the Jordan Valley and the settlement blocs remained in Israel’s hands, then the Palestinian state that would arise on the remainder of the West Bank would have territorial contiguity without shrinking Israel to indefensible proportions. A partial withdrawal, then, would extract Israel from its present trap. It would abolish Israel’s direct military rule over Palestinian civilians, while keeping Israel militarily defended.”

Such a solution, he believes, would require the Palestinians “to relinquish the right of return and Israel to relinquish land.”

Goodman is not advocating a full-blown peace treaty, but separation: “In exchange for a long-term ceasefire agreement with Israel, the Palestinians would receive a sovereign state with territorial contiguity, without having to recognize Israel and without renouncing the right of return.”

Under this arrangement, certain neighborhoods in East Jerusalem without Jewish residents or a Jewish history would form the capital of a Palestinian state, while Jewish settlements outside the main settlement blocs would be constrained from expanding beyond their boundaries.

In conclusion, Goodman writes, “The modern world calls on Israelis to lower their expectations … and to move from a politics that attempts to change reality toward a politics that finds a way to live with it instead.”

Goodman’s case for pragmatism and compromise seems reasonable and is certainly worth exploring in depth. But it’s doubtful whether the right in Israel and the mainstream Palestinian leadership would accept it.

It would appear that Israel and the Palestinians are locked into a vortex of eternal struggle.