The 25th anniversary of the historic peace treaty between Israel and Jordan went unnoticed in both countries in a telling admission of their increasingly frosty relations.

Implemented on October 26, 1994 in an upbeat ceremony in the Arava desert about a year after Israel and the Palestinians announced the Oslo accord, it was Israel’s second such agreement with a neighboring Arab nation.

Israel signed its first regional peace accord with Egypt on March 26, 1979 in Washington, D.C.

Instead of marking this important anniversary with celebrations, Israel was in a somber mood as it prepared to hand over two small parcels of land to the Jordanians on November 10. A year ago, King Abdullah II informed Israel that the Jordanian government would not renew clauses in the treaty allowing it to lease Naharayim (Baqura) and Tzofar (Ghumar) for 25 years.

Last month, Israeli Energy Minister Yuval Steinitz officially confirmed that Israel will return these lands to Jordan in November.

Naharayim, a strip of agricultural land 3.2 square miles in size, lies at the confluence of the Jordan and Yarmouk rivers. It was acquired by Israel in 1950. In 1997, a Jordanian soldier shot a group of Israeli schoolgirls at the site, killing seven. In the wake of the incident, King Hussein of Jordan made an extraordinary trip to the girls’ hometown of Beit Shemesh to offer his condolences.

Tzofar, in the southern Arava, is 7.2 square miles in size, and was gradually taken over by Israel between 1968 and 1970.

Speculation abounded that Israeli farmers in the Tzofar enclave would be permitted to continue leasing it for another season, but Jordan issued a sharp denial. Jordanian Foreign Ministry spokesman Sufyan Qudah said that Jordan’s decision was final and that the lease would neither be renewed nor extended.

Qudah’s declaration was in line with a blunt statement by Jordanian Foreign Minister Ayman Safadi last October that Jordan would not enter into negotiations with Israel over Naharayim and Tzofar. As he put it, “We will not negotiate over the sovereignty of these areas.”

Jordan’s refusal to extend the leases is a reflection of its bitterness with Israeli policies and its disillusionment with Israel’s right-wing prime minister, Benjamin Netanyahu.

Such is the mood in Jordan today that King Abdullah recently rejected Netanyahu’s request for a meeting. Abdullah’s rebuff came in the wake of his frank comment that the treaty has grown colder by the year.

The king’s attitude is not uncommon in Jordan. Last December, a government spokeswoman, Jumana Ghneimat, was photographed in a building in Amman walking over an Israeli flag in a gesture of contempt.

More astonishingly, the Jordanian prime minister who signed the peace treaty, Abdelsalam al-Majali, told an interviewer last year that Jordan should “take Haifa by force” should it be militarily strong enough to do so in the future.

Their animus toward Israel is shared by the vast majority of Jordanians. According to a poll conducted by the Konrad Adenauer Foundation, 70 percent of Jordanians would prefer to “limit” bilateral relations with Israel. So would professional associations, which categorically reject normalization. And a significant number of parliamentarians have gone as far as to call for the abrogation of the treaty. As well, the media is generally hostile to Israel.

Anti-Israel feeling in Jordan runs so deep that many public figures expressed opposition to a $10 billion deal under which Israel will supply the country with 45 billion cubic meters of natural gas over 15 years. Bowing to their pressure, the government has ordered a review of the agreement.

As is the case in Egypt, there is little or no grassroots support for the treaty, and Israel is widely regarded as an enemy.

The monarchy, however, upholds the treaty, but keeps Israel at arms length.

“The (Jordanian) government is playing a double game,” writes Israeli scholar Edy Cohen in a recent paper for the Begin-Sadat Center for Strategic Studies. “Its public hostility toward Israel enables it to preserve its popularity, while behind the scenes, it maintains good relations with Israel.”

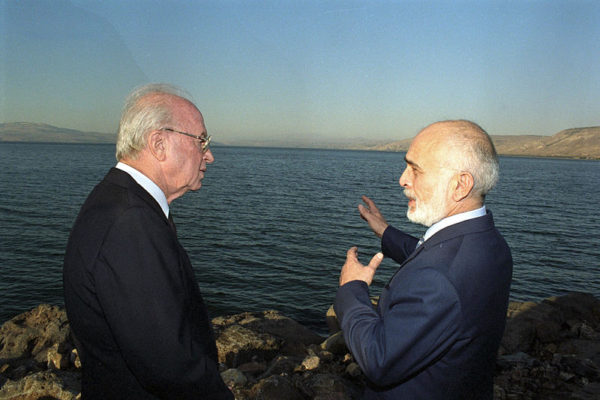

Cohen argues that Jordan’s “covert relations” with Israel are intended to please U.S. President Donald Trump and to ensure that Israel continues supplying Jordan with 50 million cubic meters of water annually from the Jordan River, the Yarmouk River and the Sea of Galilee, as stipulated in the treaty.

From Israel’s point of view, it has been beneficial. Most importantly, Jordan — which shares the longest border of all its neighbors with Israel and has fought three wars with the Jewish state (1948, 1967 and 1973) — has been neutralized as a military adversary. Since Israel regards Jordan’s stability as a key national interest, security and intelligence cooperation with the kingdom is of the utmost importance.

Israel, though, is disappointed by the anemic volume of bilateral trade. In recent years, Israeli exports to Jordan have ranged from $50 million to $100 million per annum. The Jordanian figure is almost identical. Much to its chagrin, Israel has not been able to turn Jordan into an export gateway to the rest of the Arab world.

And two-way tourism is hardly what it could be. Approximately 100,000 Israelis visited Jordan last year, primarily on excursions to Petra and Wadi Rum. Israel received only 12,ooo Jordanians, most of whom were of Palestinian origin.

Viewed in perspective, Israel’s relations with Jordan have gone through two major phases.

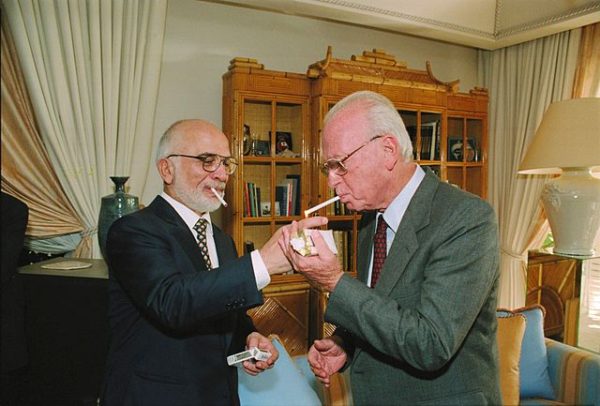

King Hussein, who crafted the treaty in league with the late Israeli Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin, forged a solid and mutually trustworthy relationship with him. Hussein’s successor, his son Abdullah, who has ruled the country since his death in 1999, has distanced himself from Israel.

It should be noted, however, that even during Hussein’s reign, Israel and Jordan were sometimes at loggerheads. In September 1997, an attempt by Mossad agents to assassinate Hamas leader Khaled Meshaal in Amman triggered a crisis, upending Israel’s diplomatic ties with Jordan.

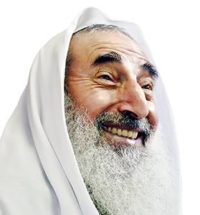

The assassins were caught but were not released until Israel provided an antidote to save Meshaal’s life and released from prison Sheikh Ahmed Yassin, Hamas’ spiritual leader.

Like his father, Abdullah supports a two-state solution, calls for Israel’s withdrawal from the West Bank, and rejects the construction of Israeli settlements there. Abdullah’s perception that Netanyahu prefers conflict management to conflict resolution has strained his relations with Netanyahu and has had an adverse effect on Israel-Jordan relations.

After Netanyahu promised to annex the Jordan Valley, Abdullah warned that the annexation would have a “major impact” on the treaty. Abdullah reportedly considered downgrading relations with Israel or recalling Jordan’s ambassador, Ghasssan Majali.

Jordan has also criticized the United States’ decision to recognize Jerusalem as Israel’s capital and to transfer its embassy from Tel Aviv to Jerusalem.

Israel, in the treaty, recognized Jordan’s special role as the custodian of Muslim holy places in Jerusalem. But in the past few years, Jordan has accused Israel of tolerating incursions by Jewish extremists into the Temple Mount compound. Two months ago, after clashes between Israeli police and Muslim worshipers, the Jordanian Foreign Ministry sharply condemned Israel.

These are not the only issues that have engendered animosity in Jordan toward Israel.

Jordan recalled its ambassador in Tel Aviv in 2000 following the outbreak of the second Palestinian uprising. Jordan was angered after an Israeli soldier accidentally killed a Jordanian judge at a border crossing in 2014. In 2017, Jordan withdrew its ambassador after a security guard killed two Jordanians in self-defence at the Israeli Embassy in Amman.

Still another source of tension is Israel’s hesitancy to build a joint water canal from the Red Sea to the Dead Sea.

Israel’s relationship with Jordan is mercurial, to say the least. But barring a disaster, Israel and Jordan will likely honor and preserve their peace treaty.