Jewish Canadians are integrated into the mosaic of Canadian society, but as Allan Levine reminds a reader in Seeking The Fabled City: The Canadian Jewish Experience, published by McClelland & Stewart, this was not always the case, a theme that frames his reflective and thoughtful work.

As he points out in the introduction, “the multicultural tolerance” that most Canadians today are so proud of dates only from the 1960s and 1970s. Until then, Jews faced all forms of prejudice and discrimination, and antisemitism was ingrained in the fabric of this country.

Representing only 1.2 percent of Canada’s population, Jews have flourished in the past 50 years. “There is likely no field of endeavor, no profession or pursuit in which a Jewish presence has not and does not continue to be evident,” he writes. “This exceptional achievement did not happen overnight.”

Home to approximately 400,000 Jews, Canada has the fourth largest Jewish community in the world after Israel, the United States and France. Nearly half live in the greater Toronto area, while 23 percent reside in Montreal and environs. The rest are mainly scattered in Vancouver, Calgary, Edmonton, Winnipeg and Halifax. It was not until the early 1920s that Canada’s Jewish population reached the 100,000 mark, or 1.42 percent of the total population, a figure that has yet to be surpassed.

Levine believes that the first Jews to set foot in what would be Canada were likely Portuguese navigators and fishermen off the Grand Banks of Newfoundland in the mid 16th century, when this country was inhabited by Indigenous people. Jews were forbidden to settle in what was known as New France, but Esther Brandeau, a Jew from a Sephardi family in France, arrived in Quebec in 1738, only to be deported in the following year.

The first real Jewish settlers were “Jew traders” like Samuel Jacobs and Aaron Hart, both of whom landed in British North America in the early 18th century. They were followed by a trickle of German and Polish Jews. By the 1830s, he estimates, some 150 Jewish merchants and peddlers lived in cities ranging from Montreal to Saint John, but their acquisition of civil and political rights was only gradual.

A handful of Jews entered into mixed marriages and baptized their children into the Christian faith. None of their descendants are Jewish today, says Levine. Highly assimilated Jews could advance. From 1888 to 1891, David Oppenheimer, a German Jew, was Vancouver’s second mayor.

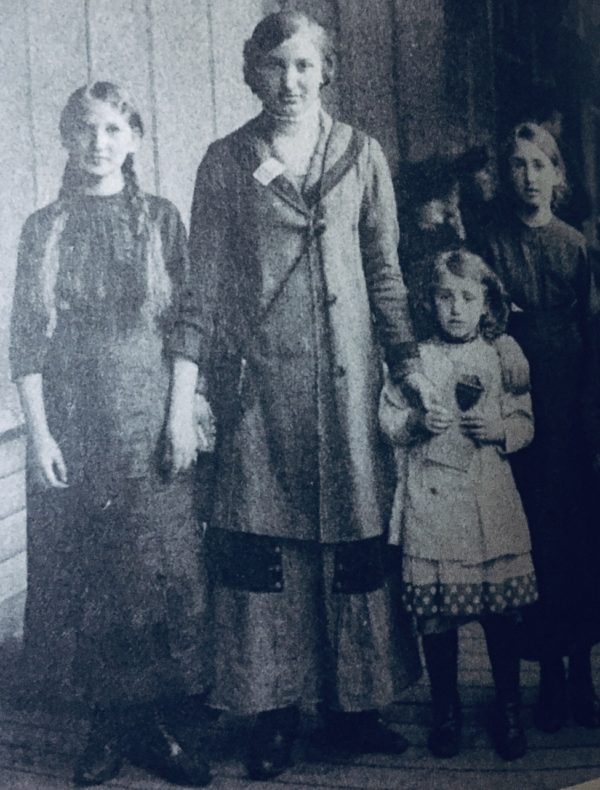

Close to 10,000 Russian and Eastern European Jews immigrated to post-Confederation Canada between 1880 and 1900, when its Jewish population reached 17,000. A tiny proportion of immigrants became farmers in Jewish colonies in the provinces of Manitoba and Saskatchewan. Eventually, most of them resettled in Winnipeg, Regina, Calgary and Edmonton.

The Jewish presence, though insignificant numerically, was opposed by nativists. One such person was Goldwin Smith, a liberal intellectual who taught modern history at Oxford University before settling in Canada in 1871.

The increasing number of Jews in Toronto in the 1920s, centered in the Spadina-Kensington Market area, prompted a daily newspaper, the Globe, to sound an alarm about “a Jewish invasion of the public schools.” The conventional wisdom was that Jews contributed to the growing poverty and congestion of the downtown core.

In Quebec, xenophobia ran deeply as well. In 1905, the Quebec City lawyer Jacques-Edouard Plamondon, influenced by the Protocols of the Elders of Zion, published a pamphlet in which he portrayed Jews as dangerous. In 1919, the principal of Queen’s University, Reverend R. Bruce Taylor, acknowledged that his policy was to keep Jewish enrollment at a low level because Jews “tended to lower the tone of Canadian universities.” The dean of McGill’s faculty of arts, Ira Mackay, claimed that “the Jewish people are of no use to us.”

During the 1920s, when antisemitism was entrenched and widely acceptable, the mainstream view was that there were too many Jews in Canada. Hotels, summer resorts, beaches and golf clubs barred Jews and their employment opportunities were limited. Le Devoir, an influential French Canadian newspaper edited by Georges Pelletier from the 193os onward, referred to Jews as “aliens, circumcised criminals, mentally ill, trash of all nations.”

Frederick Blair, the director of the government’s immigration department from 1936 to 1943, expressed opposition to allowing Jewish refugees into Canada. “The line must be drawn somewhere,” he said. The justice minister, Ernest Lapointe, Prime Minister William Lyon McKenzie King’s French Canadian lieutenant, agreed. A 1946 Gallup poll found that the two least desirable immigrants were the Japanese and Jews.

At the height of World War II, the residents’ association on Center and Ward’s islands in Toronto were accused by J.B. Salsberg, a Labor-Progressive member of the Ontario legislature, of banding together to ensure that cottages were not rented to Jews. When the province passed anti-discrimination legislation in the same year, the Globe and Mail, Canada’s self-styled national daily, protested that the bill was an affront to free speech and that “toleration” could not be advanced by “intolerant laws.”

To Levine, the passage of the Racial Discrimination Act in 1944 “marked the beginning of a decade of landmark human rights legislation which ultimately altered the way Jews and other minorities were treated in Canada, but it hardly eliminated discrimination and it certainly did not eradicate prejudice.”

As he observes, Jews still faced high hurdles. In 1948, MacLean’s magazine published a piece by the journalist Pierre Berton outlining the problems. “All the major professions … were closed closed to Jews,” he wrote. He also learned that the magazine’s parent company, MacLean Hunter, did not hire Jews either.

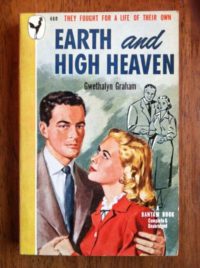

By then, antisemitism, having received critical attention from a novel which had won the Governor General’s Award for fiction four years earlier, was no longer an issue that could be swept under the carpet. Earth and High Heaven, by Montreal writer Gwethalyn Graham, was about the love affair and complicated relationship between a Protestant journalist and a Jewish lawyer. Translated into 18 languages, it was the first novel published in Canada to attain the number one position on the New York Times bestseller list.

As Canada opened its doors to Jewish immigrants after World War II, 35,000 Holocaust survivors arrived between 1947 and 1955. Among them were 2,136 tailors and their families. My late parents — David and Genia — and I were in this group.

Levine argues that Pierre Elliott Trudeau’s rise to power as Liberal Party leader and prime minister in 1968 contributed to the gradual elimination of antisemitic discrimination. “Trudeau soon became the most ‘Jew-friendly’ leader in Canadian history,” he writes. Trudeau appointed the first Jewish federal cabinet minister (Herb Gray), the first chief justice of the Supreme Court (Bora Laskin, who in the mid-1950s advised his Jewish law students not to waste their time applying for articling positions in non-Jewish law firms in Toronto), and the first Jewish ambassador to the United States (Allan Gotlieb). In the wake of these developments, Dave Barrett became the first Jewish premier of a province (British Columbia).

By this juncture, Louis Rasminsky had been appointed the first Jewish governor of the Bank of Canada and Nathan Phillips had been elected Toronto’s first Jewish mayor.

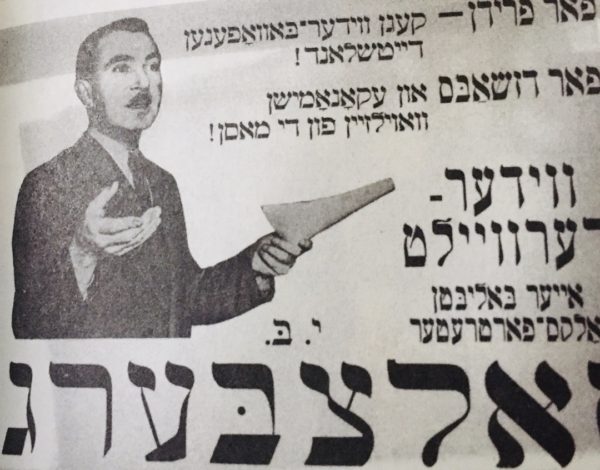

These signposts of progress did not mean that anti-Jewish animus had disappeared. Far from it. In the 1980s, Canadian Jews were transfixed by the trials of two Holocaust deniers, the German national Ernst Zundel and the Alberta high school teacher Jim Keegstra.

Now, nearly two decades into the 21st century, antisemitism, the oldest hatred, still rears its ugly head. According to a 2016 Statistics Canada document, Jews are the most targeted victims of hate crimes.

But while Jews are mindful of antisemitism, “they do not see themselves as the most significant target of persecution in this country,” says a report written by Robert Brym, Keith Neuman and Rhonda Lenton in 2018. “They are more likely to believe that Indigenous peoples, Muslims and Black people in Canada are frequent targets of discrimination, and are more likely to hold this view than Canadians as a whole.”

To some Jews, however, the steadily rising intermarriage rate is what really threatens the cohesion and integrity of Canada’s Jewish community. In the first half of the last century, the rate never rose above 10 percent. Of late, it has risen beyond 25 percent on a national level. “The wide acceptance of Jews in Canada (means) that intermarriages are no longer taboo,” says Levine.

The community, in the meantime, is growing, fed by an influx of Russians and Israelis, and Levine is confident that it will continue to grow in the future.