Megan Koreman’s book has an inspirational tale to tell.

The Escape Line: How the Ordinary Heroes of Dutch-Paris Resisted the Nazi Occupation of Western Europe (Oxford University Press) is about an intrepid network that saved lives during World War II. It’s the first work of its kind on the Dutch-Paris Escape Line, which smuggled Dutch Jews to neutral Switzerland via Paris and assisted political opponents of the Nazis and downed Allied airmen.

The author, an American historian, is the daughter of a Dutch couple who were involved in this little-known rescue operation.

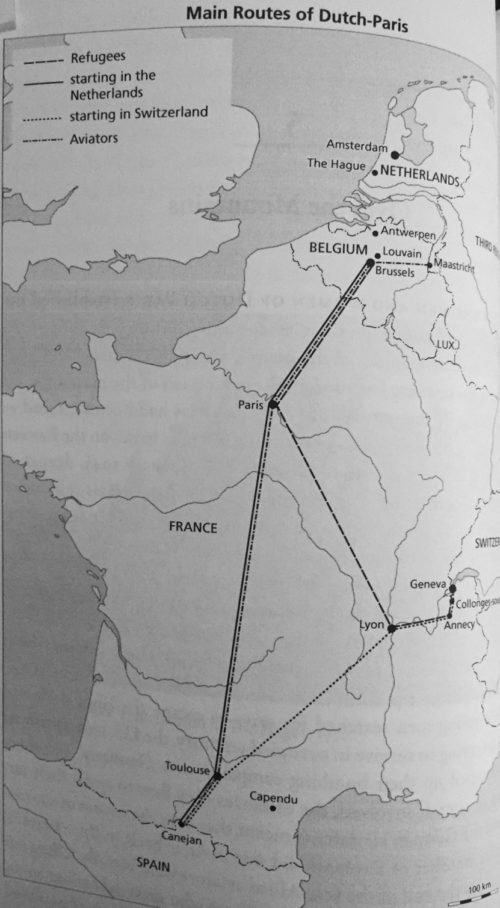

As she explains in the introduction, it functioned as a vast, clandestine welfare agency and courier service that supported 1,500 refugees in hiding and took another 1,500 to safety in Switzerland and also Spain. “The line ran through western Europe like a river of goodwill, carrying fugitives and messages out of occupied territory,” she writes, adding that it was fed by “small streams” of local resistance groups in Holland and Belgium.

Dutch-Paris, as it was colloquially known, was composed of 330 men and women primarily from Holland, Belgium, France and Switzerland. Hunted by the Nazis, they were Protestants, Catholics and Jews and spoke Dutch, French and sometimes English. A mixed group, they were students, housewives, civil servants, shopkeepers, farmers, teachers, customs officers, clergymen, businessmen, bankers and even cabinet ministers.

Apart from smuggling people in distress to safe places, they forged documents, raised money and scrounged for provisions on the black market.

“They started by helping Jews because, at that time and place, these were the people who needed help,” says Koreman. “When other people needed to escape occupied territory, they helped them to do so. It did not matter to them if the fugitive was a child of a resistance leader in danger of being taken as a hostage or an Allied airman shot down by the Luftwaffe.”

Dutch-Paris was founded by Jean Weidner, a Dutch Seventh Day Adventist businessman, in the summer of 1942 in the French city of Lyon. Weidner, whose father was a pastor, had been taught to obey the law, but he had also been raised to stand up for his principles.

He and his French wife, Elizabeth Cartier, launched Dutch-Paris by smuggling a Jewish couple into Switzerland, which in 1942 closed its border to “racial refugees.” Within weeks, they were operating an escape line between Lyon and Geneva. Having spent most of his life in France, he was very well acquainted with the French transportation system, a key component of Dutch-Paris.

As Koreman points out, every mission undertaken by Dutch-Paris incurred expenses for train tickets, black market food, false documents and passeurs, the guides who smuggled Jews and others into Switzerland. Weidner worked with reputable passeurs, but some were scoundrels who betrayed their clients and turned them over to the police.

Weidner charged affluent refugees a little extra to subsidize indigent refugees, and never turned away a refugee who could not afford to pay his or her own way. When necessary, he used his own funds to facilitate the process.

Much to his dismay, Weidner and his colleagues could not assist everyone. Koreman cites the case of Simon Eliasar, a Jew who was deported in 1943 to Drancy, a French camp near Paris, and perished in Auschwitz-Birkenau.

One of the challenges that refugees constantly faced was whether they would be permitted to remain in Switzerland. “Once over the border, refugees needed to return to strict legality in order to stay there,” she says. “The Dutch embassy supported Dutch refugees financially and diplomatically, but only those with the legal right to be in Switzerland.”

In closing, Koreman underscores the point that Dutch-Paris rescuers were essentially defenders of human rights. With every refugee and fugitive they protected, they built a “moral alternative” to Nazi Germany’s New Order.

Koreman celebrates their heroism in this workmanlike volume.