The Irish and the Jews, given their vastly different religious and historical backgrounds, are not exactly two peas in a pod. But according to Aidan Beatty and Dan O’Brien, the editors of Irish Questions and Jewish Questions: Crossovers in Culture (Syracuse University Press), they are “two of the classic outliers of modern Europe.”

As they state in the introductory essay of this illuminating volume of erudite essays, the Irish and Jewish people share a number of common experiences. They both struggled for statehood in the 19th and 20th centuries. They both had a tangled and sometimes violent relationship with a colonial power, Britain. They both sought to revive their respective ancient languages, Gaelic and Hebrew. And they both relied on a far-flung diaspora for moral, political, financial and logistic support.

Or, as R.M. Douglas, a professor of history at Colgate University, writes,” the Jews and the Irish shared “a history of foreign domination, a common experience of exile, and a commitment to …. the creation of a new nation-state in their ancestral homelands.”

“Unfortunately, these similarities pointed in the direction not of coexistence, nor even of assimilation, but of physical separation — which is one of the reasons that Sinn Fein founder Arthur Griffith, like many other European antisemites of his generation, always had kind words to say for Zionism,” Douglas caustically says. “To be Jewish in Ireland during the past century has been to live in an atmosphere whose element of menace has been more overt at some times than at others, but never wholly absent,” he adds.

Whatever the case may be, the Jews and the Irish go back a long way.

The medieval chronicle, Annals of Inissfallen, claims that the first Jews to set foot in Ireland landed in 1079 bearing gifts for the Irish king Tairdelbach, who promptly sent the five travellers packing. Jews returned in very small numbers, but, like the Jews of Britain, were expelled by royal decree in 1290. With the restoration of Britain’s Jewish community in 1656, foreign Jews, especially Dutch Sephardim, began settling in Ireland. The first synagogue was built in Dublin in the early 1700s, and the first Jewish cemetery was opened in the suburb of Ballybough during the same period. Since Ireland was an impoverished country, few potential Jewish immigrants seriously considered it, and the Jewish population remained negligible in the 18th and early 19th centuries.

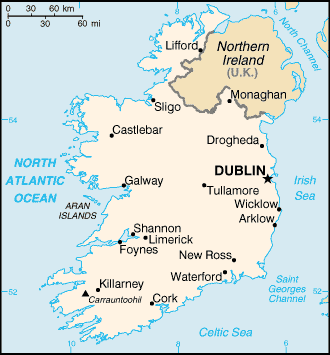

Dublin’s Jewish community of 350 in the 1880s consisted mainly of craftsmen — silversmiths, watchmakers and picture frame makers. By the 1890s, Ireland’s Jewish population reached 4,000, distributed in Dublin, Cork, Belfast and smaller centers such as Derry, Waterford, Dundalk and Limmerick.

Most of the newcomers arrived from Lithuania, and they tended to be struggling petty traders or peddlers. From the 1870s until the first decade of the 20th century, Jews were the largest foreign-born residents of Ireland. By 1946, Ireland was home to 4,000 Jews. As of a few years ago, the figure had dropped to 1,984, compared to 50,000 Muslims, 10,000 Hindus and 45,000 Orthodox Christians.

Although the majority of Jews were not closely involved in Ireland’s struggle for independence from British colonial rule, a minority actively supported it through the Judaeo-Irish Home Rule Association, which was founded in the first years of the 20th century, says Heather Miller Rubens, the executive director of the Institute for Islamic, Christian and Jewish Studies in Baltimore. Its purpose, she says, was “to put Irish Jews into closer relations with their fellow Irishmen and to correct the false conceptions about Irish Jewish insularity …”

As Beatty and O’Brien suggest, Jews have been regarded ambivalently by the Irish.

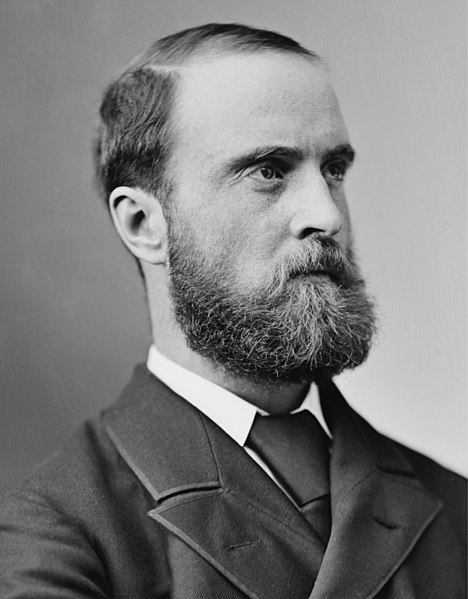

Thomas Moore, Ireland’s preeminent bard of the 19th century, sympathetically lumped Jews and Irish together, calling them “conquer’d and broken.” The historian Charles O’Connor, in Dissertations on the History of Ireland (1753), described the Irish as “a kind of ethnic Hebrews.” The philologist Charles Vallancey, co-founder of the Royal Irish Academy, linked the Irish with the Israelites. Charles Stewart Parnell, a champion of Irish home rule, compared an independent Ireland to the Promised Land.

As Jews gained a foothold in the economy, tensions with Irish traders flared. In Limerick, in 1904, a preacher initiated a boycott against Jewish businesses, forcing some Jews to leave. At the start of the 20th century, antisemitic advertisements appeared in Irish nationalist publications. During the mid-1920s, the Irish Republican Army launched a campaign against money lenders, some of whom were Jews.

As the writers in this volume suggest, antisemitism was common in Ireland before World War II.

Michael Donnellan, the head of the farmers’ party, Clann na Talmhan, referred to Jews as “aliens.” Priests in the Catholic Church, as well as Catholic intellectuals, equated Judaism with Communism. John Charles McQuaid, the archbishop of Dublin, claimed that the Depression was “the deliberate work of a few Jew financiers.”

According to Peter Hession, a lecturer at University College Dublin, Jews have been seen both as ancient and noble and as “unacceptable as individuals in modern society.” Such perceptions have led many Jews to feel they will never fully be accepted or be “Irish enough to be entirely at ease in Irish society,” says Natalie Wynn, a researcher at Trinity College specializing in Irish Jewish history.

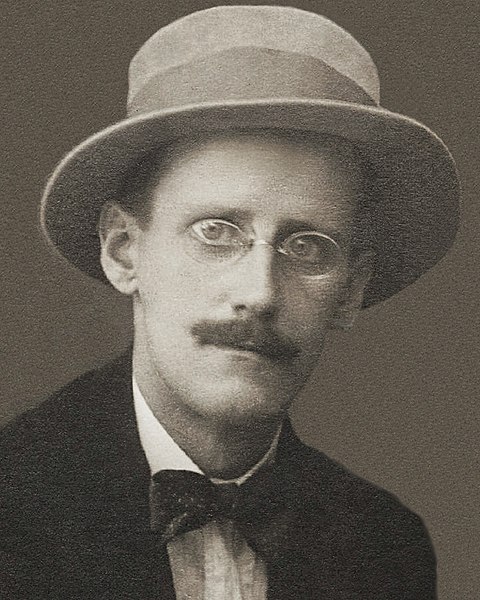

James Joyce satirized antisemitism in his novel, Ulysses, as George Bernstein, a professor of literature emeritus at the University of Michigan, points out. When the character Stephen Dedalus collected his salary from Mr. Deasy, the latter said, “Ireland, they say, has the honor of being the only country which never persecuted the jews. Do you know that? No. And do you know why? Because she never let them in.”

Not quite true. It’s a fact, however, that Ireland, in the 1930s, was reluctant to admit Jewish refugees fleeing fascism. But exceptions were made due to the efforts of Robert Briscoe, the first Jewish member of the Irish parliament and the first serving Jewish mayor of Dublin, and Isaac Herzog, the chief rabbi.

Trisha Oakley Kessler, an Irish historian, says that “a broad range of Irish voices” urged the government to block the influx of Jewish refugees into Ireland. “The arrival of Jewish refugees was not a humanitarian response to the plight of Jews in Europe,” she writes. “Decisions were determined by their use to the nation.” She points out that the policies of one of Ireland’s leader, Eamon de Valera, generally favored Jews.

The last essay in this book, by Sean William Gannon, a fellow at the Center for Contemporary Irish History at Trinity College, deals with the Irish officials who served at all levels in Mandatory Palestine. For many, their posting in Palestine was their first encounter with Jews and/or Jewish nationalism. “Occasionally friendly, but more frequently fraught, this encounter, in many cases, defined their views of Israel and Zionism for the rest of their lives,” writes Gannon.

Rejecting the principle of partition in the resolution of intercommunal conflicts, Irish members of the police force, civil service and judiciary tended to be pro-Palestinian, supporting the creation of a single Arab state in Palestine.

The thoughtful essays in Irish Questions and Jewish Questions open new avenues of inquiry into the nature of the Irish-Jewish relationship, but Wynn says that “the academic field of Irish Jewish studies remains in its infancy.”

As she elaborates, “Many areas of Irish Jewish historiography — such as Irish-Jewish relations — remain mired in the nostalgia and minority politics of a community past its prime, whose long-term future hangs in the balance. Although much has been written about the position of Jews in Irish society, rigorous, critical and objective analysis are notably absent from these assessments.”

In light of her comments, I look forward to reading more about this intriguing topic.