Zalman Shoval was Israel’s two-time ambassador to the United States during the presidencies of George H.W. Bush and Bill Clinton. Shoval, posted to Washington from 1990 to 1993 and again from 1998 to 2000, served four Israeli prime ministers. His term of office coincided with Iraq’s invasion of Kuwait, the outbreak of the first Gulf War, the convening of the Madrid peace conference, and the emergence of sharp differences with the Bush administration over the construction of Israeli settlements in the occupied areas. Israel’s bilateral relations with the United States were directly affected by these events, and Shoval’s task was to manage them.

In his thoughtful and vivid memoirs, Jerusalem and Washington: A Life in Politics and Diplomacy (Rowman & Littlefield), Shoval, now 89, ranges over this tumultuous period in exacting detail, while recalling his childhood in Danzig, his immigration to Mandatory Palestine in 1938, and his career in Israeli politics, which started in 1970 when he was elected to the Knesset to replace David Ben-Gurion, the first prime minister of Israel.

Shoval’s parents, Saul Finkelstein and Olga Rabinowitz, were East European Jews whose relatives were murdered by the Nazis. “My father foresaw what was about to happen and got us out a short time before the great conflagration,” he writes in reference to the Holocaust.

Expecting a catastrophe to envelop European Jews, Shoval’s father bought a house in Tel Aviv in 1934 and hired a Hebrew tutor for him and his sister. In 1936, he set sail for Palestine aboard an Italian ship. “I fell in love with Tel Aviv at first sight, and my love affair with the city has never ended.” He adds, “My integration into the surrounding society was extremely easy and rapid.”

Describing his idyllic youth in cosmopolitan Tel Aviv, Shoval, a right-wing Zionist, readily admits he was blind to the approaching disaster in Europe and unaware of the “problematic nature of the Arab question.”

The 1948 War of Independence broke out while he was a student at the University of California, Berkeley. He studied journalism but was soon drawn to diplomacy. Returning to Israel in 1952 after receiving an advanced degree in international relations in Geneva, he joined the army’s Intelligence Corps. Discharged with the rank of lieutenant, he joined the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. In 1956, he married Kena Mayer, his “secret weapon,” and then began working for the Export Bank, her father’s private company.

Politically, Shoval found his place in Rafi, a breakaway faction of the ruling Mapai Party formed by Ben-Gurion and his protege, Shimon Peres, a future prime minister and president. A self-styled “dovish hawk,” Shoval did not subscribe to the doctrine of Greater Israel but supported Israel’s retention of the territories it had captured in the 1967 Six Day War. One of the founders of the Likud Party, he opposed “foreign sovereignty” over “parts” of the Land of Israel. In plain language, he did not believe the Palestinians were entitled to statehood in the West Bank and the Gaza Strip.

After Likud’s victory in the 1977 general election, Shoval rejected a position as deputy minister of industry and trade, but was willing to accept an appointment as one of Foreign Minister Moshe Dayan’s deputies. Dayan eventually appointed him as his advisor on public diplomacy, and Shoval focused on Israel’s peace negotiations with Egypt.

During the 1982 war in Lebanon, Shoval was an army spokesman. “The situation in Lebanon at that time can only be described as surreal,” he says. “In various parts of the country, including Beirut itself, fighting raged, but on the beach at Jounieh, young men and women in scanty bathing attire continued sunning themselves undisturbed.” To Shoval, the outcome of the war was less than ideal. By his reading, Israel missed an “opportunity of historic proportions” to resolve the Palestinian problem, and Hezbollah replaced the PLO as the dominant military force in southern Lebanon.

Yitzhak Shamir, the Israeli prime minister, proposed Shoval as ambassador to the United States. It was regarded as a “political” appointment, but Shoval believes that a political appointee can better represent the incumbent prime minister.

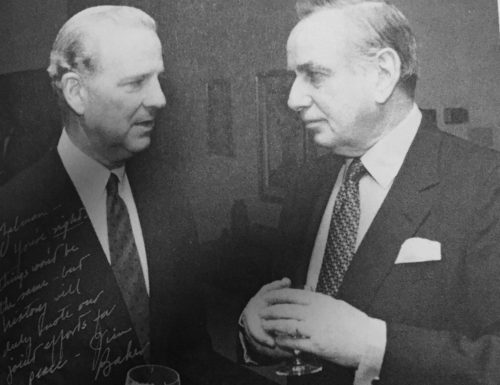

Shoval’s relationship with U.S. Secretary of State Jim Baker grew tense after Baker refused to accept an assurance from the Israeli government that American loan guarantees for the absorption of new Russian immigrants would not be used for settlements beyond the old Green Line. It was an issue that would not be resolved until the Clinton presidency.

In an aside, Shoval writes, “On one of my stays at the Plaza Hotel (in Washington), a tall gentleman approached my table and introduced himself as its owner: Donald Trump. He told me straight away that he thought that the way the (Bush) administration dealt with us on the loan guarantees was very unjust. He wished me good luck and left. That was my only meeting with the future president.”

The Israeli government fully supported Bush’s decision to wage war against Iraq in 1991, but Israel had to be very careful not to be seen as a warmonger, he notes. The United States strongly cautioned Israel not to react militarily to an Iraqi attack. Baker vigorously rejected Iraq’s attempt to create a link between the crisis in the Middle East and the Arab-Israeli conflict, but he implied that the United States would try to resolve Israel’s dispute with the Palestinians.

With the eruption of the Gulf War, Iraq fired the first of 39 Scud missiles at Israel. Shoval says he advised Shamir not to respond so as to preserve the U.S.-led Arab coalition ranged against Iraq and to keep Israel’s relations with the United States on an even keel. Israeli Defence Minister Moshe Arens, however, argued that the absence of a response would fatally damage the credibility of Israel’s deterrent capability. “No one belittled this reasoning, certainly not Shamir or me,” says Shoval. “But Shamir was predisposed against responding militarily to anything but a non-conventional weapons attack.”

When Arens met Bush in Washington during the course of the war, he claimed that the Patriot missile batteries that Israel had received from the United States to shoot down Iraqi Scuds had proved to be “useless.” Shoval’s assessment is more balanced: “In retrospect, both sides were right. The Patriot did indeed intercept some of the incoming missiles, but the combined damage caused by the Patriot and Scud debris was greater than that of the Scud on its own.”

In the aftermath of the war, Baker, in a meeting with Shamir, told him that Israeli settlements had caused damage to the prospects of peace. “Shamir, who usually listened in silence and allowed his guests to finish what he was saying, stopped him and said emphatically, ‘But this is our land!'”

Shoval suggests that Shamir intrinsically understood that the Palestinian delegation at the Madrid peace conference identified with and answered to the PLO, which Israel did not recognize. And he acknowledges that neither Israel nor Syria were prepared for compromises at that particular juncture. Later on in his book, Shoval discloses that he and Benjamin Netanyahu, then a candidate for the Likud Party’s leadership, both rejected a U.S. proposal for an Israeli withdrawal from the Golan Heights, even if Israel’s security needs were met and Syria agreed to normalize relations with Israel.

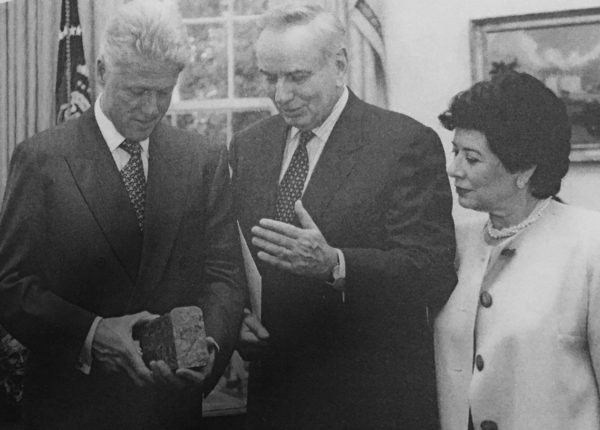

Yitzhak Rabin, Shamir’s successor, asked Shoval to stay on at his post. “In both character and worldview, Rabin was much closer to the Republicans than the Democrats,” he says. Rabin agreed to deduct the sums that Israel would allocate to settlements from the $10 billion loan guarantees — “a formula that Shamir had refused to accept.” Shoval was pleased with the compromise: “I viewed it as one of the most important achievements of my diplomatic career.”

Shoval’s personal relations with Israel’s new foreign minister, Shimon Peres, was complex. As he puts it, “In Rafi’s initial period, I was considered one of his confidants, but I refused to return to the Labor Party with him and later joined the Likud. Moreover, it seems to me, he developed a grudge toward me after the Yom Kippur War, when I disagreed with his claim that Dayan’s standing had been irreparably damaged.”

Shoval gave up his ambassadorship in 1993 and was replaced by the Middle East scholar Itamar Rabinovich. As an advisor to Netanyahu after his 1996 election victory over Peres, Shoval advised him to honor the 1993 Oslo agreement. But Shoval was anything but a dove, calling for a “permanent arrangement with the Palestinians in which Israel would establish security zones in Judea and Samaria with a Jewish majority and include most of the Jewish settlements in them.” He adds, “My colleagues and I all perceived Jews’ right to the Land of Israel as a basic given, but reality dictated the need to take other considerations into account: security, demography (and) diplomacy.” This all boiled down to “defensible borders” for Israel, he says.

Shoval admits he aspired to be foreign minister, but the job already had been promised to David Levy, a Likud apparatchik. Netanyahu reappointed Shoval as ambassador, and he returned to Washington with instructions that Israel’s policy was not “land for peace” but “land for security.”

In the spring of 2000, Shoval went back to Israel. And in September of that fateful year, he accepted an offer from Ariel Sharon, the Likud leader, to join him on a walk to the Temple Mount in East Jerusalem. He accepted the invitation out of curiosity and a spirit of adventure. Sharon’s stroll ignited the second Palestinian uprising, but he disagrees with that thesis. Shoval, though, concedes that the Temple Mount visit was “unnecessary” and “in some respects harmful.”

Shoval supported in principle Sharon’s plan for a unilateral Israeli withdrawal from Gaza. But he soured on it because it was not part of a comprehensive strategy and therefore lacked legitimacy.

In closing, he sets out his views of Israel’s dispute with the Palestinians.

Historically, they have not ideologically come to terms with the notion that the Jews are entitled to statehood in an Arab and Muslim region. “For propagandist and diplomatic reasons, the Palestinians were occasionally prepared to recognize Israel as a ‘fact’ (preferably a temporary one), but not the legitimacy of Israel’s existence. Therefore, the various ideas raised as comprehensive solutions are, in the main, irrelevant and unrealistic.”

Proceeding from that assumption, Shoval rejects Palestinian statehood, claiming the concept is “replete with drawbacks and threats.” But Israel should not necessarily settle for the status quo or sit on its hands politically and diplomatically, he warns.

With chaos spreading in the Middle East, he recommends interim arrangements whereby the Palestinians would obtain “increasing management of their affairs in those spheres that do not harm, in the broadest sense, Israel’s security needs.”

Shoval’s solution, local autonomy, does not even meet minimum Palestinian demands. But that’s as far as he’s prepared to go.