Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu recently voiced optimism that his proposal to annex the Jordan Valley and Jewish settlements and outposts in the West Bank was virtually a fait accompli.

Expressing confidence that the United States would recognize his plan, which would give Israel a permanent eastern border for the first time in its history, Netanyahu declared, “We have an opportunity that hasn’t existed since 1948 to apply sovereignty (to the West Bank), and we will not let this opportunity pass.”

Saying he would start this momentous process in July, he assured his right-wing base that the 60,000 Palestinians living under Israeli rule in the Jordan Valley would not be eligible for Israeli citizenship.

Netanyahu has been advocating annexation since his attempt to shore up right-wing support in advance of the April 2019 election.

He is under pressure to act swiftly because Joe Biden, the former U.S. vice-president, may defeat President Donald Trump, a supporter of Netanyahu’s agenda, in November’s presidential election.

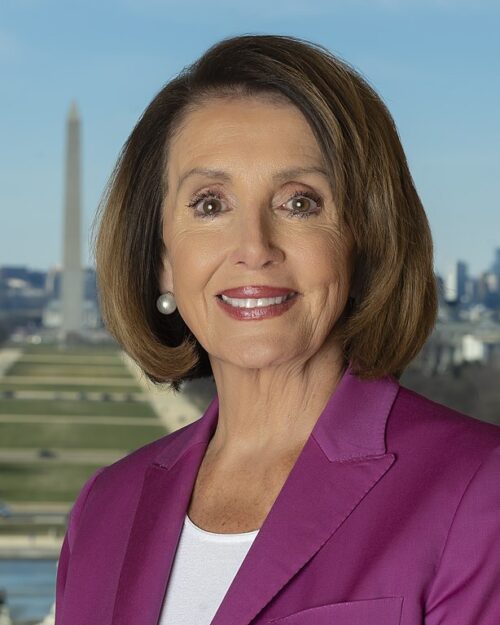

Biden, a champion of a two-state solution, has come out against annexation, as has the Speaker of Congress, Nancy Pelosi, who said it will undermine American national security interests.

Much to his frustration, Netanyahu may have to delay implementation of annexation. The Trump administration wants to slow it down, and some of his supporters in the West Bank settlement movement will oppose it unless Washington’s peace plan is overhauled to their satisfaction. In their view, it is detrimental to Israel’s national interests.

The truth of the matter is that the U.S. plan is largely tilted in Israel’s favor.

Unveiled in January, and diverging from traditional U.S. policy on the Arab-Israeli conflict, it endorses Israel’s annexation of roughly 30 percent of the West Bank and calls for a non-contiguous Palestinian state, with limited sovereignty, in 70 percent of the West Bank.

The Palestinians, however, would not achieve statehood unless they comply with a series of onerous U.S. demands.

The Palestinian Authority would have to recognize Israel as a Jewish state, accept Israeli security control of the Palestinian entity, abandon the dream of the right of return of Palestinian refugees, disarm its Hamas rival in the Gaza Strip, and settle for the Jerusalem suburb of Abu Dis as its capital.

Israel accepted the plan without reservation, but the Palestinian Authority denounced it as completely one-sided and unacceptable.

By the terms of an agreement reached between Netanyahu and his chief coalition partner, Blue and White Party leader Benny Gantz, annexation can be brought to the Knesset for a vote as early as July 1.

It is also understood that Israel cannot annex territory in the West Bank unless it is done in coordination with the United States.

Shortly after the American plan was released, the U.S. ambassador to Israel, David Friedman, a staunch supporter of settlements, said the Israeli government could proceed to annexation immediately.

Within hours of his brash announcement, Trump’s senior advisor and son-in-law, Jared Kushner, slammed the brakes on Friedman’s suggestion. He said that annexation should be postponed until a joint U.S.-Israeli team has completed the task of mapping every nook and cranny of the West Bank. This project has nearly ground to a halt due to the coronavirus pandemic.

More recently, Kushner reportedly told Netanyahu in a conference call that the United States would prefer to “downplay enthusiasm” for immediate annexation and “greatly slow” it down.

Kushner’s comments appeared to mark a change in tone in U.S. policy.

Last month, in a comment welcomed by Netanyahu, U.S. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo said the status of the West Bank would be determined by Israel. “As for the annexation of the West Bank, the Israelis will ultimately make those decisions,” he told told reporters. “That’s an Israeli decision.”

Not exactly.

Shortly after Pompeo issued this statement, Friedman issued a clarification, saying the United States would recognize annexation only if Israel abides by two conditions: freezing settlement construction in areas of the West Bank assigned to a Palestinian state and resuming direct negotiations with the Palestinians on the basis of the U.S. plan.

The last time Israel and the Palestinian Authority were engaged in direct talks was in 2014.

The 450,000 settlers in the West Bank are also proving to be something of an obstacle in Netanyahu’s quest for annexation.

First, they vehemently oppose any form of Palestinian statehood. Second, they are concerned that the U.S. plan will consign 15 settlements to disconnected enclaves in Palestinian territory, thereby isolating them from Israel, stifling their growth, and ending the religious Zionist dream of gaining control over the entire West Bank.

Netanyahu has tried to assure them that Trump’s plan is in their fundamental interest.

As he put it the other day, “President Trump’s vision for peace includes a requirement of the Palestinians to recognize Israel as a Jewish state, Israeli security control throughout the territory west of Jordan, a unified Jerusalem, the disarming of Hamas, ending the right of return for Palestinian refugees to enter Israel, and more.”

A minority of settlers living close to Israel’s pre-1967 Green Line have grudgingly come to terms with the U.S. plan and thus have endorsed Netanyahu’s proposal to annex the Jordan Valley.

But a substantial number of leaders in the settlement movement, notably David Elhayani — the chairman of the Jordan Valley Regional Council — have rejected the American plan.

According to Elhayani, it is not in Israel’s security and settlement interests and only serves the needs of the United States. Incredibly enough, Elhayani also said that Trump and Kushner “are not friends of the State of Israel.”

Elhayani and his colleagues have demanded a copy of the map delineating Israel’s future border, but Netanyahu has refused to provide one.

Netanyahu has condemned Elhayani’s remarks, saying that Israel cannot go ahead with annexation unless it is fully supported by the United States. Netanyahu’s confidant, Yarviv Levin, the Speaker of the Knesset, has branded these settlers as unparalleled ingrates who not do appreciate the value of Israel’s alliance with the United States.

Having reminded them that Trump is Israel’s “great friend,” Netanyahu listed the valuable “gifts” he has bestowed on Israel: recognition of the legality of the settlements, recognition of West and East Jerusalem as Israel’s capital, the transfer of the U.S. embassy from Tel Aviv to Jerusalem, and recognition of Israel’s sovereignty over the Golan Heights.

Netanyahu has offered to pass the settlers’ concerns to the U.S./Israeli mapping committee, but they remain adamant and threaten to “blow up” his plan to annex the Jordan Valley.

As a sop to the settlers, Energy Minister Yuval Steinitz has said that Israel will only accept portions of the American plan that meet its requirements. “We didn’t announce that we’re adopting the Trump plan, but rather parts of it, including the part that lets us extend Israeli law to settlements and the Jordan Valley,” he said.

Despite the resistance Netanyahu is encountering from super hardline settlers like Elhayani, 52 percent of Israeli Jews back the annexation of parts of the West Bank, according to the Israel Democracy Institute.

Outside of Israel, opposition to annexation has been steadily building.

The United Nations Middle East envoy, Nickolay Mladenov, has condemned it, saying it would “destroy any hope of peace.” In April, he told the Security Council, “It would constitute a serious violation of international law, deal a devastating blow to the two-state solution, close the door to a renewal of negotiations and threaten efforts to advance regional peace.”

On April 30, 11 European ambassadors to Israel warned Israel of severe consequences if it annexes the Jordan Valley and the settlements.

Yesterday, the foreign ministers of Russia and Egypt, plus Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau, rejected annexation.

Netanyahu has disregarded their justifiable warnings, but he cannot push annexation through the Knesset unless the United States and the majority of settlers are fully on board.

This issue is likely to come to a head in the next few weeks, if not sooner.