Havana, Cuba’s capital, has seen better days.

A gleaming, modern, hip city more than 60 years ago, Havana fell on hard times following the 1959 revolution, when the new left-wing government, headed by Fidel Castro, deposed the corrupt pro-American Batista regime.

Subjected to a U.S. economic embargo after the Cuban government nationalized private property, Cuba was thrown into a state of austerity, if not outright poverty. During this revolutionary period, Havana lost a lot of its lustre as its vast ensemble of historic buildings began showing signs of wear and tear, peeling, decaying and crumbling under the weight of neglect and a new set of national priorities.

After all these years, much of Havana, population 2.1 million, is sadly faded and decidedly dilapidated. But Havana, a UNESCO World Heritage site founded in the early 16th century by a Spanish conquistador, is not without its intrinsic charms.

Usually baking under a warm or hot tropical sun, depending on the season, Havana grew prosperous in the 16th and 17th centuries, when the wealth of Latin America passed through it en route to Spain. In what is now old Havana, rich merchants constructed stately homes, while the municipality built beautiful cobble-stoned plazas adorned with monumental statues and imposing churches.

By the mid-1930s, Havana had morphed into a playground, a venue of conspicuous consumption and rampant vice, with locals and foreigners alike frequenting hotels, casinos and clubs owned, in large part, by a faction of the U.S. mafia under the control of Meyer Lansky.

Castro and his cohorts changed all that, turning back the clock in an effort to eradicate all forms of American mercantile domination.

As a result, Havana is hardly as lively, freewheeling and entrepreneurial as it was during the halcyon republican era, which lasted from 1902 to 1959. Nonetheless, it`s still well worth visiting, if only to catch a glimpse of the capital of the only communist regime in the Americas.

Start your tour in Revolutionary Square, in central Havana, where brutalist concrete-cast buildings reminiscent of the Soviet Union remind visitors of the bitter ideological struggles of the 20th century. Castro, in his heyday as Cuba`s heroic leader, would deliver long-winded speeches here to adoring masses.

Look around the gigantic square and you`ll see a statue of Jose Marti, a Cuban nationalist icon; a likeness of Che Guevara, a revolutionary martyr, on the facade of a non-descript building; Cuba`s toothless parliament and the national library.

You`ll also see what passes for a common sight in Havana — a cavalcade of shiny, candy-colored vintage American cars, lovingly preserved by their proprietors.

Like most tourists, you`ll be taken to a factory or shop selling Cuban cigars and rum. The Romero & Julieta store, redolent of tobacco, was jammed with loud, curious foreigners.

The private crafts market, near the shabby port area, was disappointing. The paintings, trinkets, wooden boxes and jersies, representing the first stirrings of capitalism since Castro`s coup, were crude, banal and forgettable, not in the same league as handicrafts from, say, India and China.

Bored by it all, I wandered off into a decaying working-class neighborhood adjacent to the market, hoping to stumble upon the real Cuba.

On one narrow street, I stopped to admire an exquisitely intricate Moorish-style green door on an otherwise drab building. Walking down a deserted lane, I read graffiti scrawled on a wall: Socialism is irrevocable.

As I returned to the market, I watched an elderly caucasian man, clad in a blinding white cotton outfit, bend slightly forward to kiss a young black woman, who was wearing a tight short skirt. I wondered whether their relationship was of a commercial nature.

Dropped off in old Havana, which the Cuban government has partially refurbished in the past decade, I visited its most famous plazas.

San Francisco Square, filled with graceful buildings of bygone epochs, was brightly sunlit. Old Square was dotted with pastel buildings affixed with before and after renovation photographs. Arms Square, the seat of power in Cuba for four centuries, was pleasantly tree-lined, with majestic colonial buildings on its western side. Cathedral Square, just as elegant, was frequented by women in frilly colorful dresses hawking trinkets and posing for photographs.

As I walked around, I passed numerous restaurants and cafes whose outdoor patios were packed with people, mostly tourists, enjoying meals, drinks and conversation.

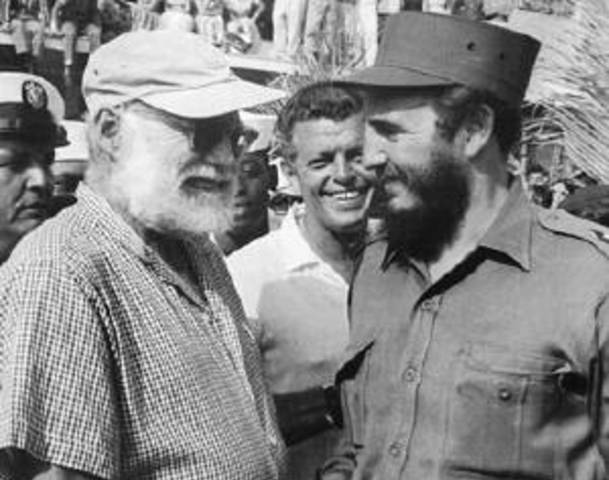

I paused at the five-storey Hotel Ambos Mundos, where the American novelist Ernest Hemingway began writing one of his classics, For Whom the Bell Tolls. Fading photographs of Hemingway hang on the walls of the lobby. In one photograph, the bearded novelist is shaking hands with a slim, youthful, smiling Castro.

Hemingway lived on a farm near Havana from 1939 until 1960. After leaving Cuba, he moved to Idaho, where he committed suicide in 1961.

Two of the most handsome buildings in Havana are in the business district, a 10-minute ride from the Hotel Ambos Mundos.

The pre-1959 parliament, known as El Capitolio Nacional, looks remarkably like the U.S. Congress in Washington, D.C. Built in 1929, it houses the Cuban Academy of Sciences and the National Museum of Natural History, which is open to the public. Down the street a bit is the grandest building in Havana, the Grand National Theater, a masterpiece of 19th century architecture.

The sea wall, or Malecon, is still one of Havana`s greatest sights. Hugging the Atlantic Ocean, it attracts young men and women as well as couples, and is ideal for strolling and breathing in the pungent salt air. Havana`s modest skyline can be seen from the Malecon, as can the U.S. diplomatic office, a fenced-in gray building with no distinguishing characteristics.

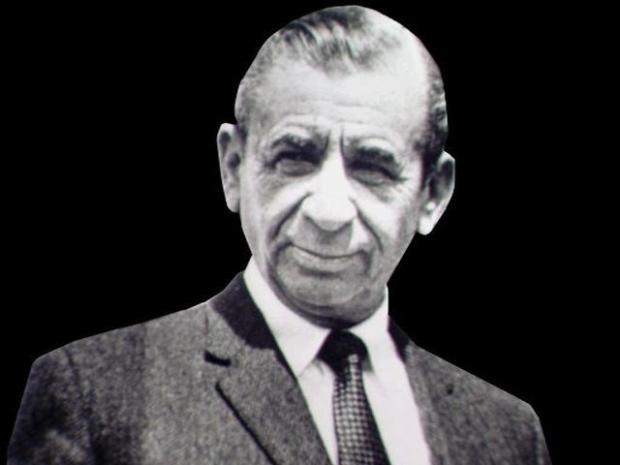

On a whim, I visited one of the last Jewish community buildings in Havana, the Centro Hebreo Sefaradi de Cuba, which also serves as a Conservative synagogue. One of three shuls in Havana, it caters to the needs of Havana`s 600 remaining Jews. Throughout the rest of Cuba, I was informed, there are another 1,000 Jews.

Prior to the revolution, Cuba was home to about 15,000 Jews, but many left in the 1960s, settling in Miami, Florida, only 90 miles from Havana, but an eternity away in all other respects.