The ongoing nation-wide protests in favor of racial equality and justice in the United States, following George Floyd’s wanton murder while in police custody, underscore America’s historically dual approach to race relations.

As Martin Luther King Jr. wrote in Where Do We Go From Here?, a book published in 1967, “Ever since the birth of our nation, white America has had a schizophrenic personality on the question of race. She has been torn between selves — a self in which she proudly professed the great principles of democracy and a self in which she sadly practiced the antithesis of democracy.”

These contradictory undercurrents were never more apparent than during the short-lived Reconstruction era, which lasted from the early 1860s to 1877. One of the most pivotal periods in America, Reconstruction is also one of the most misunderstood.

Henry Louis Gates, Jr., the director of the Hutchins Center for African American Research at Harvard University, delves deeply into this momentous epoch in a masterful work, Stony The Road: Reconstruction, White Supremacy, and the Rise of Jim Crow, published by Penguin Press.

Reconstruction led to the effective disenfranchisement of black male voters in former Confederate states and the imposition of the “separate but equal” doctrine throughout the country, but it was originally intended to create a biracial democracy out of the wreckage of the U.S. Civil War.

A revolutionary moment, Reconstruction narrowed “the gap between its ideals and laws and advanced racial progress,” he writes.

Beginning with the passage of the Civil Rights Act and the ratification of the Thirteenth, Fourteenth and Fifteenth constitutional amendments, Reconstruction both granted four million formerly enslaved persons freedom, citizenship and an array of political, civil and economic rights and readmitted conquered the Southern states of the Confederacy into the United States.

During Reconstruction, African Americans were given the right to vote, and more than 2,000 served in office at the local, state and federal levels. But by the early 20th century, not a single African American politician could be found in Congress.

A counter-revolution, spearheaded by Southern Democrats and aided and abetted by the North, thwarted this monumental effort.

As the “bayonet rule” of the North’s military occupation ended, white resistance to Reconstruction intensified with the formation of reactionary Redemption governments, the creation of the Ku Klux Klan and the imposition of so-called “black codes” that rolled back the fleeting epoch of egalitarianism. These developments paved the way for Jim Crow segregationist laws and the wholesale disenfranchisement of black voters in the 1890s. This marked the nadir of American race relations.

As Gates points out, even abolitionists, who had fervently supported the abolition of slavery well before the Civil War, did not necessarily endorse equal rights for black people. “In other words, the Civil War ended slavery, but it didn’t end anti-black racism,” he says.

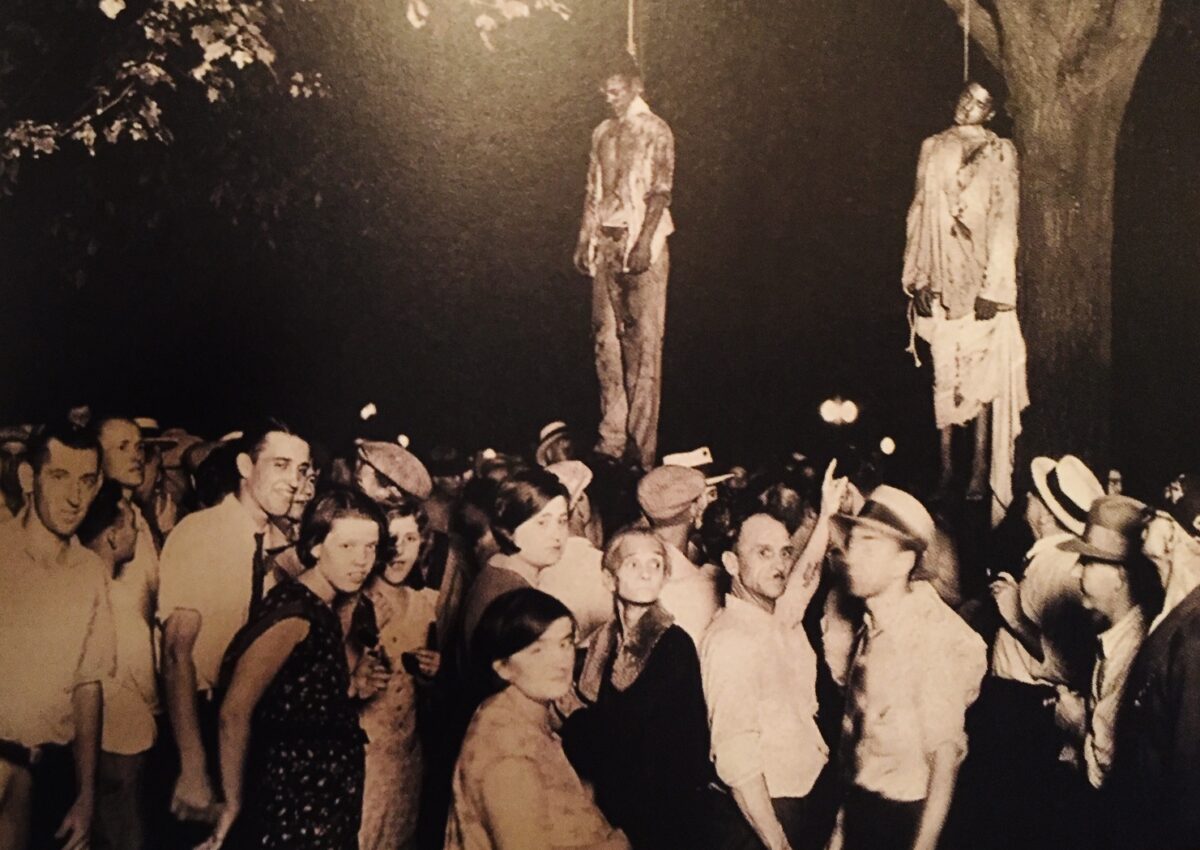

With the crumbling of Reconstruction, white supremacism triumphed. African Americans were subjected to violence, lynchings and verbal and visual debasement to deflate their popular image in American culture. In the meantime, white landowners replaced slavery with sharecropping, an oppressive system which also affected poor whites.

Southern intellectuals who laid the groundwork for Redemption included Edward A. Pollard, a journalist and the author of the highly influential polemic, The Lost Cause: A New Southern History of the War of the Confederates. Pollard argued that the withdrawal of the South from the Union had not been an act of treason but rather a revolt against an unjust Northern federal government, and that slavery had not caused the Civil War. While many Lost Cause advocates grudgingly accepted the demise of slavery, they rejected the notion of racial equality.

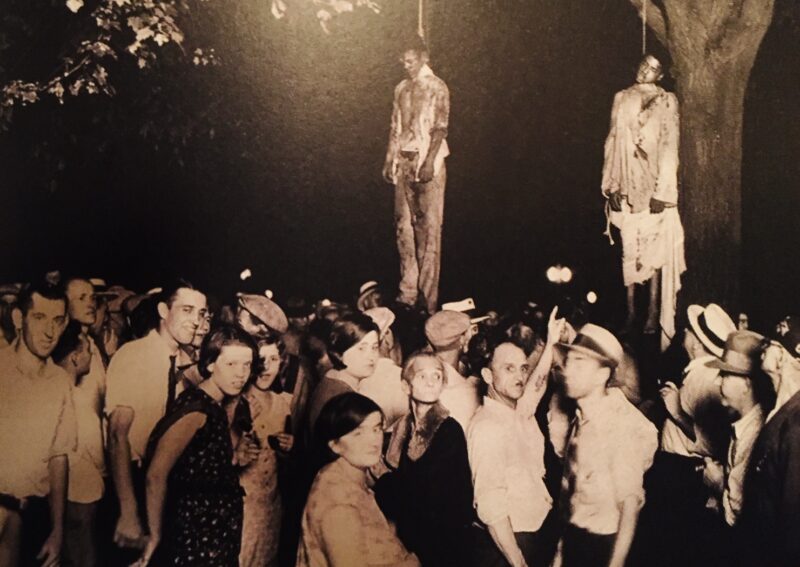

Nevertheless, some African American leaders, notably Frederick Douglass, hailed Reconstruction as the dawn of a new era. Little did he know that Abraham Lincoln’s successor in the White House, Andrew Johnson, was a white supremacist opposed to granting black people suffrage or property under land redistribution programs. After meeting Douglass, Johnson snidely said, “He’s just like any nigger and would sooner cut a white man’s throat than not.”

Constitutions in Southern states guaranteeing black men civil rights were accordingly struck down. Commenting on Mississippi’s decision to disenfranchise its black population, James Kimble Vardaman, a future governor and U.S. senator, acknowledged it had been done for no other reason than “to eliminate the nigger from politics.”

In quick succession, the U.S. Supreme Court dismantled black voting rights and dismissed laws banning African Americans’ access to all manner of services and public accommodation. And in the landmark Plessy vs. Fergusson case of 1896, the separate but equal ruling was passed, consigning black people to full-blown segregation.

Segregationists deployed science to justify their position.

In 1866, the provisional governor of South Carolina, Benjamin Franklin Perry, opined that “the African has been in all ages a savage or a slave. God created him inferior to the white man in form, color and intellect, and no legislation can make him his equal.”

Fifteen years later, the Atlantic Monthly carried a piece claiming that the “uncouth, strangely shaped animal-looking Negro or mulatto … belongs to a race entirely distinct from that of the white race.”

Henry Grady, the editor of the Atlanta Constitution, delivered a speech in 1886 in which he brazenly romanticized the unequal and often abusive relationship between “the Southern people (and) the Negro.” In his opinion, they were “close and cordial.”

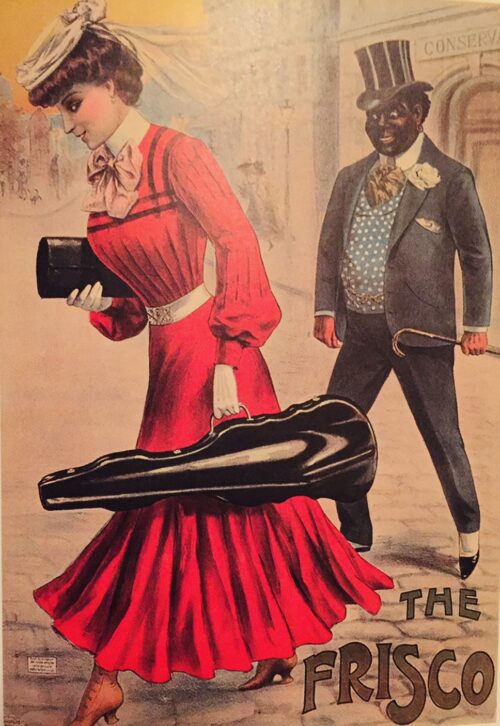

Southerners like Grady promoted the new genre of “plantation literature” and “Sambo” art, writes Gates.

Joel Chandler Harris, who worked for Grady before transitioning into fiction writing, created one of the most infamous characters in American literature, Uncle Remus, the archetype of the contented and avuncular black man.

“Uncle Remus embodies the popular postbellum idea that plantation life and work were more preferable for black southerners than the alternative, namely city life in an industrializing ‘New South’…” says Gates. “He suggests furthermore that Reconstruction had achieved very little and that efforts to advance black southerners’ civil rights and material well-being had only interfered with a social system whose adherents knew best how to accommodate each other.”

F. Hopkinson Smith was yet another novelist who patronized African Americans. His book, Colonel Carter of Cartersville, was rife with racist dialect. Before turning to the printed word, he worked as an engineer, building the foundation of Liberty Island, the home of the Statue of Liberty, the symbol of American freedom. Gates revels in this irony.

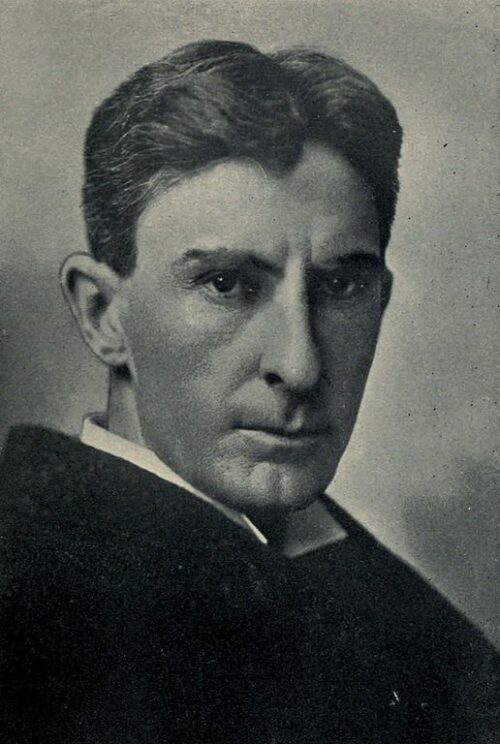

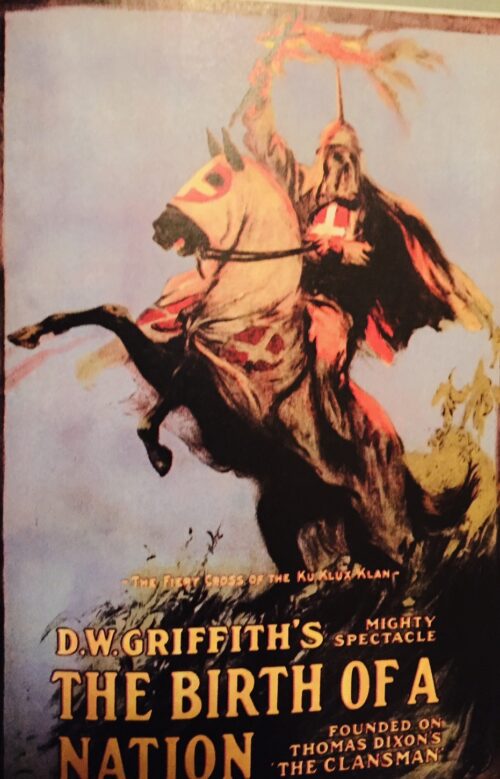

According to Gates, no Southern writer had a more lasting impact on arousing enmity toward free blacks than Thomas Dixon, a staunch white supremacist. His most important book, The Clansman: An Historical Romance of the Ku Klux Klan, was published in 1905, at the height of Jim Crow, and was turned into a silent film, The Birth of a Nation, by D. W. Griffith in 1915. Gates describes it as “one of the most blatantly racist motion pictures ever produced.”

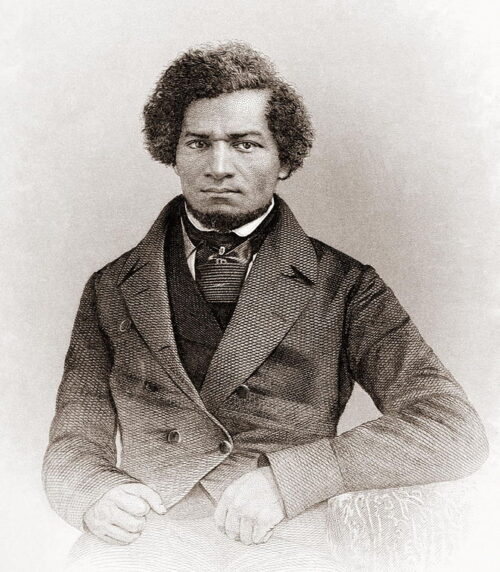

Sambo art, which became immensely popular, portrayed African Americans as infantile and easily led, yet dangerously brutal.

The perils of interracial dating and miscegenation loomed large as a recurring theme in Southern politics, with black males being seen as sexual predators and rapists. For a white Southerner, there was nothing worse than the defilement of a white woman by an African American male.

Gates devotes a chapter to the “New Negro,” the class of educated, middle-class African Americans who were expected to combat the mounting injustices faced by black Americans after Reconstruction. Embodying the same social and moral values as whites, they dressed like their white counterparts and spoke in standard English rather than in a black dialect.

One of its leading representatives, Booker T. Washington, was an accommodationist who was prepared to accept segregation on condition that African Americans were allowed to achieve economic progress through manual labor and the trades.

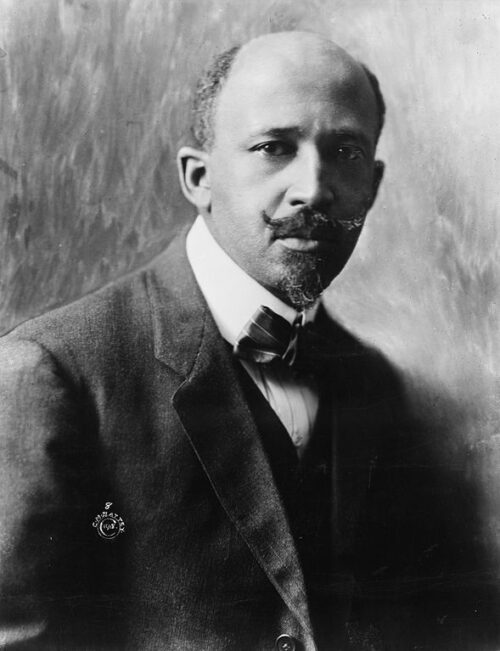

Washington’s policy was rebuffed by W. E. B. DuBois, the first black man to earn a PhD at Harvard. He fought back as the gains of Reconstruction vanished and segregation took hold. But he warned that the “first and greatest step toward the settlement of the present friction between the races lies in the correction of the immorality, crime and laziness among the Negroes themselves, which still remains as a heritage of slavery.”

Despite his efforts, anti-black racism in the South increased, prompting a major demographic shift, the migration of millions of poor sharecroppers to Northern cities.

In closing, Gates focuses on the New Negro Renaissance, or the Harlem Renaissance, a consequential movement of art and literature that became a vital component of the African American quest for civil rights. It did not produce the desired results, and decades would elapse before African Americans would achieve a measure of racial equality.

But as the tragic George Floyd affair amply illustrates, the Promised Land of a genuine egalitarian America still lies far off in the distance.