Andrzej Krakowski was one of the victims of the antisemitic campaign that drove multitudes of Jews out of Poland in 1967 and 1968. Crudely disguised as an anti-Zionist reaction to Israel’s military victory in the Six Day War, it was primarily rooted in an ideological struggle within Poland’s ruling Communist Party that pitted Western-leaning progressives against Soviet-backed conservatives.

Krakowski, then a university student and the son of a senior government official, was hounded out of Poland, like thousands of culturally assimilated Polish Jews who considered it their beloved homeland. By some estimates, upwards of 30,000 Jews emigrated, bound for destinations ranging from the United States and Israel to Sweden and Denmark.

Krakowski’s one hour and 35-minute documentary, Farewell To My Country, was released in 2002, but it has stood the test of time and is now available on Amazon Prime.

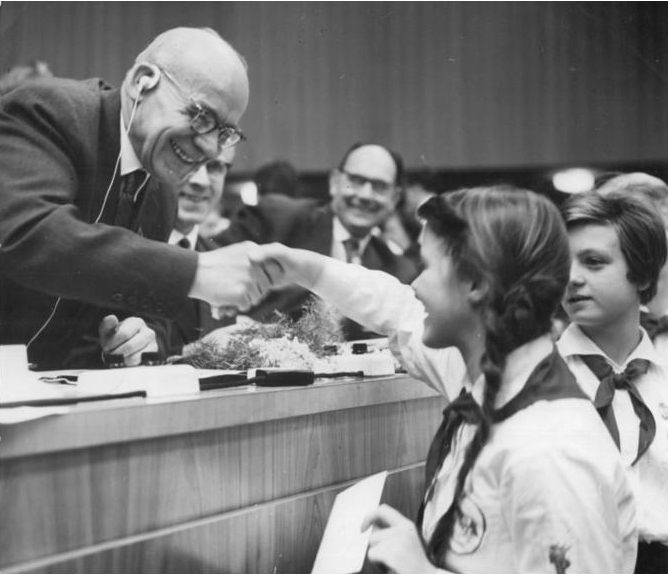

Consisting of brief interviews with Polish Jews, and interspersed with file footage of Communist Party leader Wladyslaw Gomulka fulminating against “Fifth Columnists” and Zionists, the film leaves the unmistakable impression that the explicit antisemitism that surfaced in 1967 was little more than a replay of the deeply-ingrained and widespread antisemitism that plagued the 3.3 million Jews of Poland before World War II.

In Krakowski’s view, antisemitism was “unwritten state policy” during much of the postwar Communist era, with purges uprooting Jews from government positions periodically. Krakowski’s father was the director of the state tourism bureau and his mother was a journalist, but strangely enough, he neglects to mention them. He mostly focuses on the children of Jews who were driven out of Poland under duress.

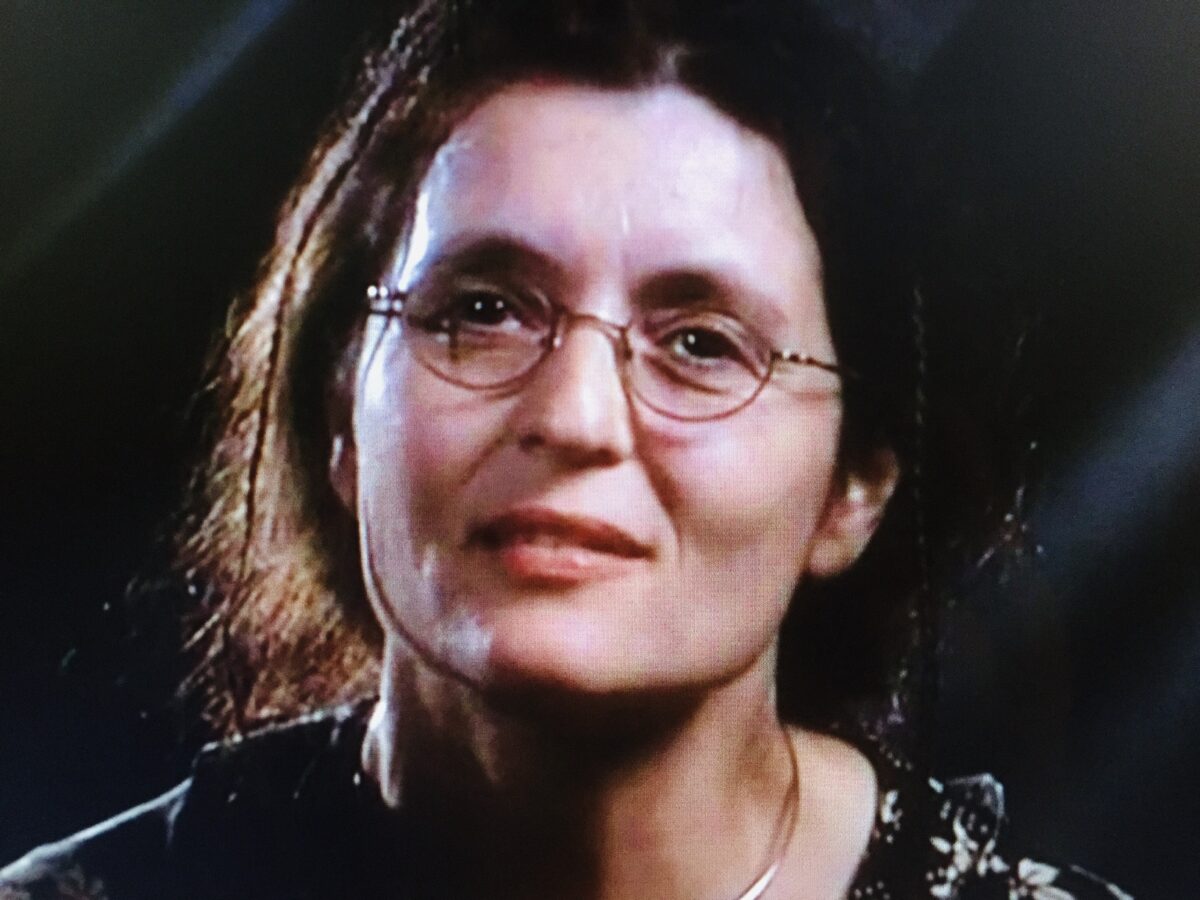

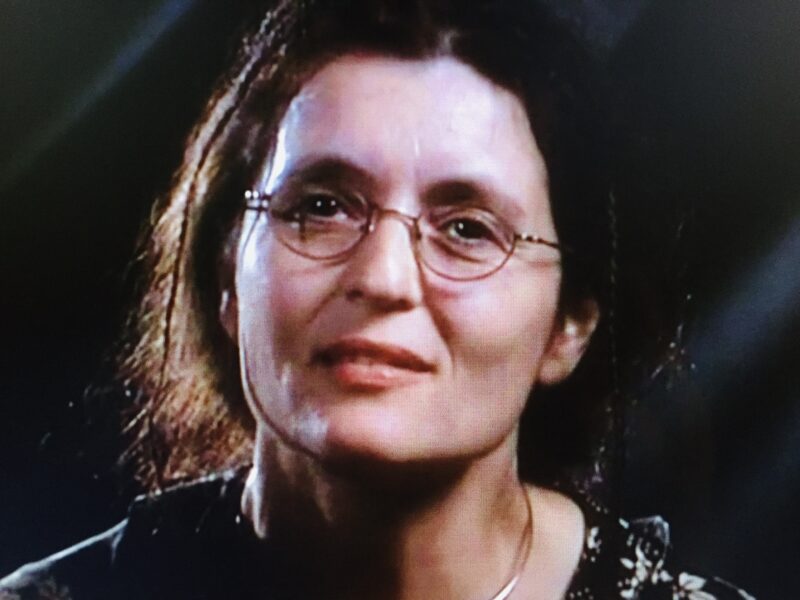

Some Jews were not even aware of their Jewish background until the moment they were denounced as Jews. Anna H of Montclair, New Jersey, falls into this category. At a school playground, she was taunted as a “dirty Jew,” a common enough epithet in Poland. Until then, Anna had no idea she was Jewish. Her mother belatedly set her straight. The discovery jolted Anna. “You couldn’t have given me worse news,” she recalls. “I was really disappointed. As far as I was concerned, being Jewish was a curse.”

As Krakowski suggests, self-hatred among some Jews who desperately sought to blend into Catholic Poland after the catastrophe of the Holocaust was not exactly an uncommon phenomenon. Anka K’s father severed ties with his Jewish family and married a Christian woman. Still other Jews regarded themselves as Poles of Jewish descent rather than as Jews per se. As one man says, “We felt we were Polish.”

To their collective dismay, these class of Jews could not escape the long arm of ethnocentrism. Antisemitism was woven into the fabric of Polish society.

Julian I, now living in Uppsala, Sweden, remembers being beaten by neighborhood bullies en route to school. Teresea K of Bethesda, Maryland, speaks of the chill she experienced after her boyfriend’s grandmother applauded the Nazi mass murder of Jews in the Warsaw ghetto.

Janusz W of Warsaw, whose parents remained in Poland after 1968, says his father, a colonel in the army, was forced into retirement.

Jozef, an elderly man who wrote impassioned letters to his son abroad, describes the “humiliation and misery” thrust upon him by Poland’s decision to ostracize Jews.

“We realized Poland wasn’t our country anymore,” laments Szymon F of Copenhagen, Denmark.

Bronek D of Fogelsville, Pennsylvania, looks back with anger as he remembers the hostile phone calls his Jewish friends received prior to their departure from Poland.

The antisemitic campaign launched by the Communist regime more than 50 years ago was a watershed in modern Polish history, an event that nearly stripped Poland of its venerable Jewish community.

Farewell To My Country distills the shock, pain and sorrow of that momentous upheaval.