White supremacist John Timothy Earnest attacked a synagogue in Poway, California, on the last day of Passover in 2019, killing a 60-year-old congregant and wounding its founding rabbi. In a manifesto posted online, Earnest, 19, invoked an incident that occurred on Easter Sunday in 1475 in the town of Trent. As he wrote, “You are not forgotten Simon of Trent, the horror that you and countless children have endured at the hands of the Jews will never be forgotten.”

The event to which he referred, which took place in that Italian town in the foothills of the Alps, still resonates in the minds of Christians who dislike Jews.

On that fateful day in March, as Trent’s tiny Jewish community ushered in Passover, rumors began circulating that a toddler named Simon has been murdered by Jews. His corpse was soon discovered in a canal running under a house owned by a Jewish family.

Simon’s death had immediate repercussions. In short order, the Jewish males of Trent were arrested, tortured and executed, and subsequently their wives and children were forced to convert to Christianity.

The vile accusation levelled against the Jewish inhabitants of Trent turned on the allegation that they killed killed Christian children for ritual purposes. A pernicious myth linked to Jesus’ suffering and crucifixion, it originally emerged in England in 1144 following the mysterious death of a 12-year-old boy, William of Norwich.

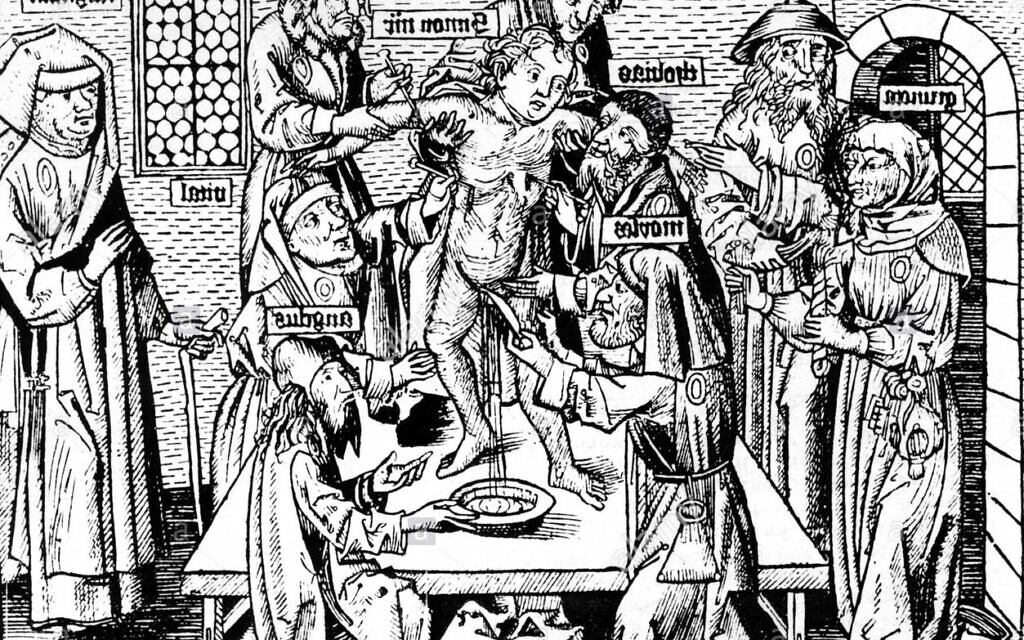

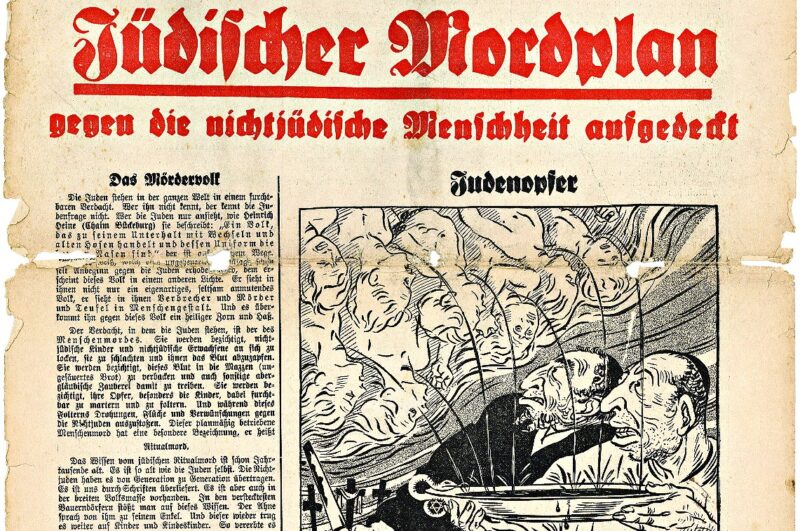

By the 13th century, a new and chilling motif was added: Jews killed Christian children to obtain their blood, turning ritual murder into blood libel and setting the stage for further popular anti-Jewish animosity throughout Europe.

“Simon’s death led to one of the most notorious and best-documented trials against Jews, to the proliferation of visual representations of the imagined deed, and, ultimately, to the undermining of the medieval protection of Jews against similar accusations,” Magda Teter writes in her illuminating book, Blood Libel: On The Trail Of An Antisemitic Myth, published by Harvard University Press.

Church and secular authorities initially condemned blood libels, as she points out. “Yet they persisted, despite evidence to the contrary, remaining deeply ingrained in European culture and imagination,” says Teter, a Fordham University history professor.

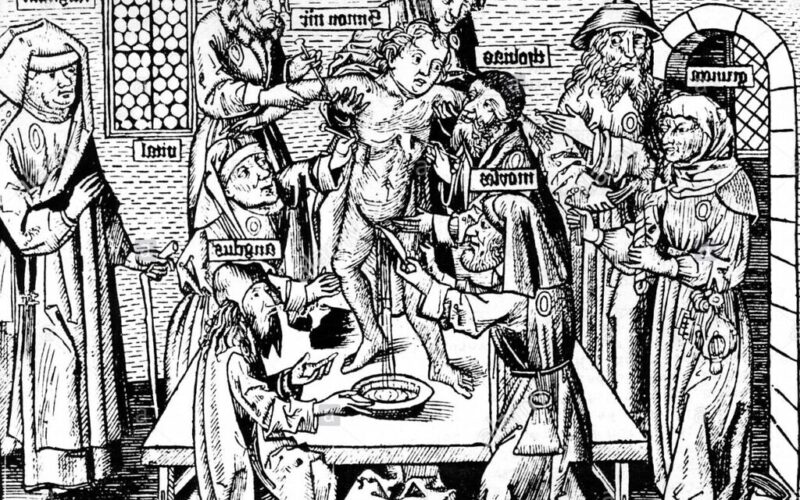

Emperor Frederick II of the Holy Roman Empire denounced blood libel in 1236, the first monarch to do so. Nine years later, Pope Innocent IV weighed in with the first papal denunciation. But after Pope Paul III’s condemnation of blood libel in 1540, his successors dodged the issue, forcing imperilled Jews to invoke earlier papal decrees.

As the centuries wore on, the myth revolving around the cult of “little Simon” gained traction and credence, disseminated far and wide by the invention of the printing press in the 15th century. In addition to printed works, it was spread by means of murals, woodcuts and engravings.

The Jewish convert to Christianity, Johannes Pfefferkorn, promoted this calumny. Jacob Frank, another convert whose acolytes adopted Christianity, claimed that the Talmud affirmed the need for Christian blood in Jewish rituals. Surprisingly, perhaps, this theme was even embraced by one of the most renowned Hebraists of the day, Sebastian Munster.

It was, of course, a profoundly moronic and ridiculous canard. As defenders of Jews tirelessly reiterated, the consumption of human blood was absolutely prohibited by Judaism.

Amid anti-Jewish disturbances in Poland in the mid-18th century, a Roman Catholic luminary, Cardinal Lorenzo Ganganelli, the future Pope Clement XIV, compiled a report methodically refuting blood libel.

Yet it was never published by the church. “The report remained a secret document unknown beyond the small circles of Vatican officials until the nineteenth century, when a new wave of charges hit Jews across Europe and the Middle East,” says Teter.

Among other blood libel incidents, she cites the Damascus affair of 1840 and the Beilis case in Russia in 1911. Interestingly enough, Ganganelli’s report was partly instrumental in Menachem Mendel Beilis’ acquittal following a lengthy and sensational trial.

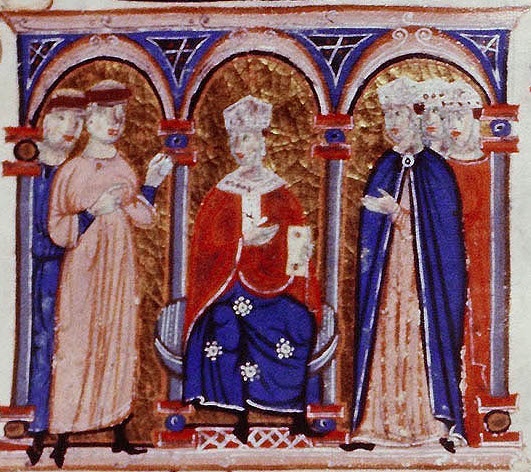

In 1927, the canard turned up in, of all places, Massena, New York. And during the Nazi era in Germany, Julius Streicher’s ferociously antisemitic newspaper, Der Sturmer, published a special edition on May 1, 1934 devoted to ritual murder. The lurid headline in big red letters read, A Jewish Plan to Murder Non-Jews Uncovered.

The blood libel myth triggered a pogrom in the Polish city of Kielce in 1946 that claimed the lives of more than 40 Jewish Holocaust survivors. And in 2014, the Anti-Defamation League issued an appeal to Facebook to delete a page titled Jewish Ritual Murder.

That such a vicious myth has endured for so long is a telling commentary on the intractable nature of antisemitism, as Teter suggests in Blood Libel.