During the first week of July, Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan announced that Hagia Sophia, a popular museum in Istanbul that was originally a cathedral and then a mosque, would be repurposed as a mosque again. In a rhetorical flourish, he added that Hagia Sophia’s reconversion was a precursor to “the liberation” of the Al-Aqsa mosque in East Jerusalem, which was conquered by Israel in the 1967 Six Day War.

His provocative comment was not a mere slip of the tongue, but a veiled threat intended to curry favor with his Islamic and nationalist base and to solidify his position as a champion of the Palestinian cause and a critic of Israel.

In May, Erdogan lashed out at the Israeli government over its plan to annex parts of the West Bank, condemning it as a violation of international law.

And in January, he blasted U.S. President Donald Trump’s newly-unveiled Middle East peace proposal. Erdogan was annoyed that it assigned all of Jerusalem to Israel and deprived the Palestinians of the possibility of establishing the capital of their future state in Jerusalem’s eastern neighborhoods. “Jerusalem cannot be left to the bloody claws of Israel,” he declared.

Before the Trump administration recognized Jerusalem as Israel’s capital, Erdogan threatened to sever relations with Israel if the United States went through with this move.

Taken together, Erdogan’s comments indicate that Turkey — which voted against the United Nations’ 1947 Palestine partition plan but which was the first Muslim country to recognize Israel — has no intention of significantly improving its currently tense and mercurial relationship with Israel.

Erdogan’s hostile attitude was surely a source of disappointment to Israel’s highest-ranking diplomat in Turkey at the moment, Roey Gilad, the charge d’affaires in Ankara. Three months ago, in an essay for the Turkish online publication Halimiz, he called for a resumption of normal bilateral ties between Israel and Turkey.

Turkey expelled Israel’s ambassador, Eitan Naeh, in May 2018 after Israeli troops killed dozens of Palestinians in the Gaza Strip trying to cross the internationally recognized border into Israel. Israel retaliated by ordering Turkey’s consul in East Jerusalem to leave.

These developments occurred just two years after Israel and Turkey — the only Muslim member of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization — finally patched up their relations following a violent 2010 incident in the Mediterranean Sea. In May of that year, Israeli commandos boarded the Mavi Marmara, a vessel in a flotilla of Turkish ships attempting to break Israel’s siege of Gaza, and killed nine Turks following a scuffle that injured several Israeli soldiers.

Turkey — which upgraded its diplomatic mission in Israel to a full-fledged embassy in 1980 — angrily recalled its ambassador in Tel Aviv and downgraded relations with Israel across the board. It was the third time since 1981 that Turkey had taken such a drastic step to demonstrate its displeasure with Israel’s policies.

In the aftermath of the Mavi Marmara affair, Turkey and Israel launched what would be a lengthy and arduous process of negotiations to repair the damage. The United States lent its assistance to facilitate these reconciliation talks.

The two sides eventually reached an agreement that enabled the Israeli and Turkish ambassadors to return to their respective posts in Ankara and Tel Aviv. Israel issued an apology and offered compensation to the families of the victims. But Israel did not bow to Turkey’s demand to end its blockade of Gaza, which was seized by Israel’s arch enemy, Hamas, in 2007. As a goodwill gesture, Turkey — which has good relations with the Hamas regime in Gaza — promised to expel Hamas operatives in Ankara.

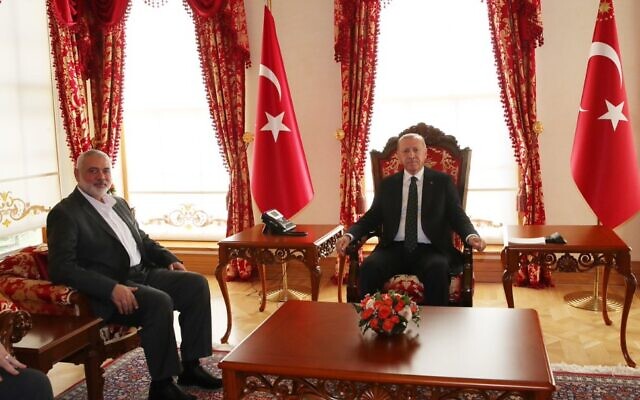

Within months of their rapprochement, Erdogan broke his silence and began launching verbal attacks against Israel. This came as no surprise to observers. Like all Islamist political parties in the Middle East, Erdogan’s Justice and Development Party (AKP) is pro-Palestinian and is partial to Hamas, the Islamic Resistance Movement.

The AKP assumed power in 2002, at the close of an unprecedented period of excellent Israeli-Turkish relations. This short-lived phase began after Israel and the Palestine Liberation Organization signed the 1993 Oslo accord, which raised hopes that the Arab-Israeli dispute could be resolved by diplomatic means. In the wake of Oslo, Tansu Ciller became the first Turkish prime minister to pay a visit to Israel.

Turkey, whose relations with Israel have always been directly affected by this conflict, was encouraged by the Oslo breakthrough and by Israel’s peace treaty with Jordan in the following year. But with the eruption of the second Palestinian uprising in 2000, which lasted until Israel’s unilateral withdrawal from Gaza in 2005, the glow of Oslo gradually faded, chilling Israel’s ties with Turkey.

Erdogan, the then prime minister, denounced Israel’s 2004 assassination of Sheikh Ahmed Yassin, Hamas’ spiritual leader, as a “terrorist act.” Nevertheless, Erdogan visited Jerusalem in 2005, in his first and only trip to Israel. And in 2007, Turkey mediated indirect talks between Israel and Syria and invited Shimon Peres, Israel’s president, on a state visit, during which time he addressed the Turkish parliament.

The first Gaza war, which broke out in late 2008 and ended in the first month of 2009, was a turning point in Israeli-Turkish relations. Erdogan regularly denounced Israel as a “terrorist” state after that. During the next two wars in Gaza, in 2012 and 2014, Erdogan denounced Israel with equal vehemence.

In the past year or so, Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu has abandoned the niceties of diplomacy and responded in kind to Erdogan’s harangues. These bitter exchanges underscore the fact that Netanyahu and Erdogan do not like or trust each other. The consensus in both countries is that real normalization cannot be achieved unless they retire from the political scene.

Today, Turkey and Israel still bicker over the perennial Palestinian question and remain at odds over the issue of Kurdish independence in Iraq. A few years ago, Israel endorsed Kurdish statehood in Iraqi territory, but Turkey, with a large Kurdish population, came out vigorously against it.

Israel and Turkey have also clashed over the natural resources of the eastern Mediterranean Sea.

Early in 2020, Israel, Greece and Cyprus signed an agreement to build a $7 billion, 1,180-mile EastMed pipeline to carry natural gas to Europe. Israel, which discovered immensely lucrative gas fields beneath its territorial waters, is also a member of the Eastern Mediterranean Gas Forum, whose members include Egypt and Jordan.

Regarding these agreements as detrimental to its interests, Turkey has warned Israel that the EastMed pipeline cannot be built without its approval. Last November, the Turkish Navy forced an Israeli survey ship to leave disputed waters in the Mediterranean.

Meanwhile, Israel and Greece — Turkey’s old nemesis — have consolidated their relationship. Last month, Netanyahu conferred with Greek Prime Minister Kyriakos Mitsotakis in Jerusalem to discuss tourism and cooperation in various fields.

In an interview with the Israeli media, Mitsotakis chided Turkey. “Turkey is undermining stability in the region,” he said in a sharp critique of Turkey’s policy. “It aims to control politically and militarily the entire area of the eastern Mediterranean. Turkey is welcome to give up its imperial pipe dreams and become part of our area of cooperation. But only as an equal, lawful partner, not as the neighborhood bully.”

Israel and Turkey, however, share common interests.

Despite their political differences, two-way trade is booming. Turkish exports to Israel include cars, concrete, minerals, textiles, ceramics and machinery. Turkey imports chemicals, electrical equipment and plastic and rubber products from Israel. Prior to 2009, Turkey bought Israeli military equipment.

Recently, Israel’s national carrier, El Al, resumed cargo flights to Turkey after a pause of a decade.

Israel and Turkey both seek to limit Iran’s influence in the region, especially in Syria, which has been embroiled in a civil war since 2011. Nonetheless, Turkey and Iran have good relations. On June 15, Iranian Foreign Minister Mohammed Javad Zarif visited Turkey.

To some extent, Israel shares vital intelligence information with Turkey, which has been enhancing its status as a regional power by virtue of military interventions in Syria’s and Libya’s civil wars. With these conflicts roiling the region, the director of the Mossad, Yossi Cohen, and his Turkish counterpart, Hakan Fidan, have met on at least two occasions in the past year.

In addition, Israel and Turkey have a mutual interest in averting a humanitarian crisis in Gaza, whose anemic economy can barely support its population.

It’s clear that Israel and Turkey have good reasons to be on friendly terms. But as the last few decades amply illustrate, this is easier said than done.