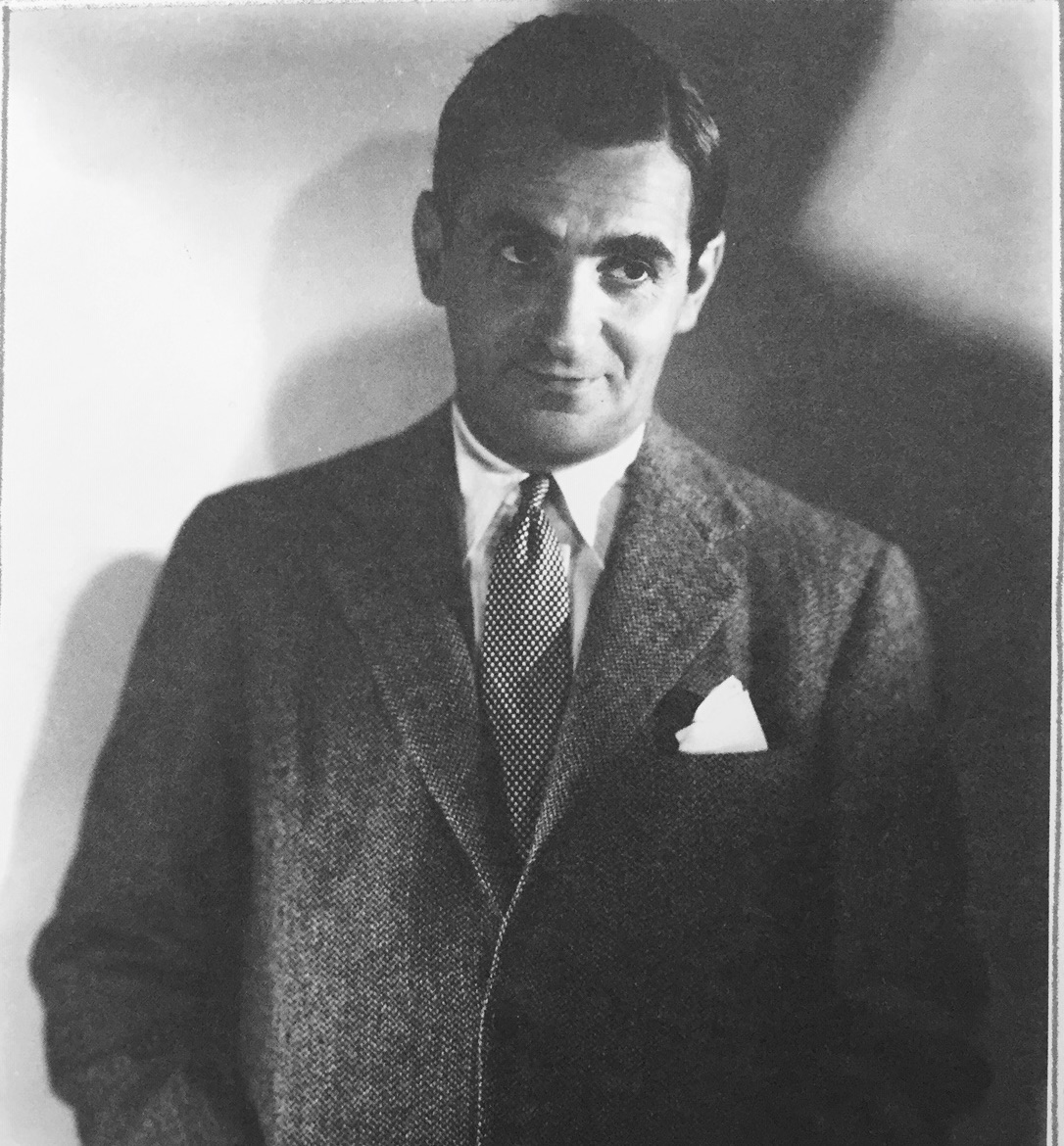

Irving Berlin, the legendary American composer and lyricist, wrote some 1,500 songs, including God Bless America and White Christmas, and two Broadway musical hits, Call Me Madame and Annie Get Your Gun, and was widely considered the greatest songwriter of the 20th century.

“Berlin has no place in American music,” his fellow composer, Jerome Kern, wrote in 1925, long before he had composed his most memorable songs. “He is American music.”

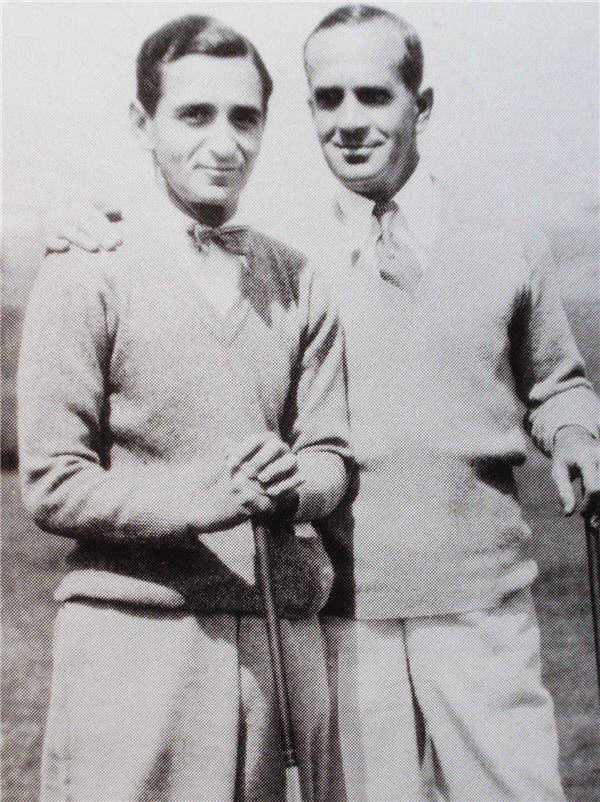

James Kaplan’s engaging biography, Irving Berlin: New York Genius (Yale University Press), takes a reader from his birth in Russia in 1888 to his death in New York City in 1989. Kaplan, a journalist who specializes in chronicling the lives of major figures in the entertainment business, shows us every side of Berlin, from his days as a singing waiter in Manhattan to his years as the reigning master of the American popular song genre.

Israel Baline, as was originally known, was the eighth and youngest child of an itinerant cantor from the western Siberian town of Tyumen. Like many late 19th century Russian Jews, the Balines headed for the United States to escape persecution and economic hardship. They arrived in New York in September 1893 and settled into a crowded Lower East Side tenement.

Often unemployed, Berlin’s father, Moses, also earned a living as a butcher, kosher chicken inspector and painter. Eager to help his struggling family, Berlin became a busker on the sidewalks of New York. “He could sing,” writes Kaplan. “He could keep a tune. He could remember the words. He could, if the spirit or the audience moved him, fill in better, spicier, words of his own.”

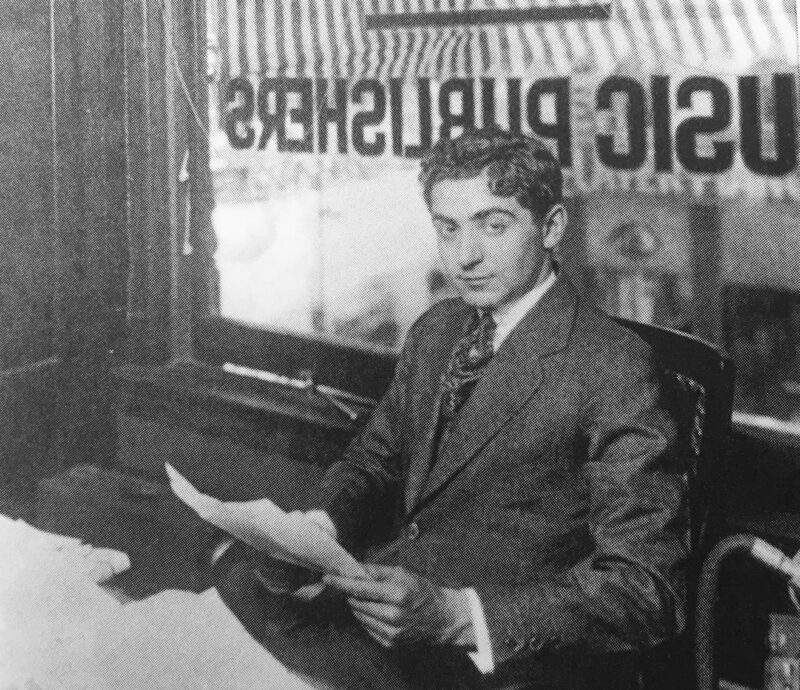

At 14, he won a spot on the chorus line of a musical. And then he was hired as a song plugger at a salary of $5 a week. He landed his first steady job, as a singing waiter, in a saloon and dance hall that doubled as a bordello. He wrote his first published song, Marie From Sunny Italy, in 1907, earning 75 cents in royalties that year.

In 1910, he wrote his first hit song, Alexander’s Ragtime Band, which Variety declared “the musical sensation of the decade.” Berlin earned $40,000 in royalties in the first year, the equivalent of almost a million dollars today. Berlin’s songs, characterized by the resonance of repeated words, were Jewish in spirit, says Kaplan.

Not every song he churned out was worth the effort. “I wrote more lousy songs than almost anyone else,” he acknowledged years later.

But Berlin had a knack for getting it right. One of his classics, A Pretty Girl Is Like a Melody, was heard at the premiere of the Ziegfeld Follies Of 1919. Another one, Blue Skies, brightened a lackluster Broadway show that closed after only 39 performances.

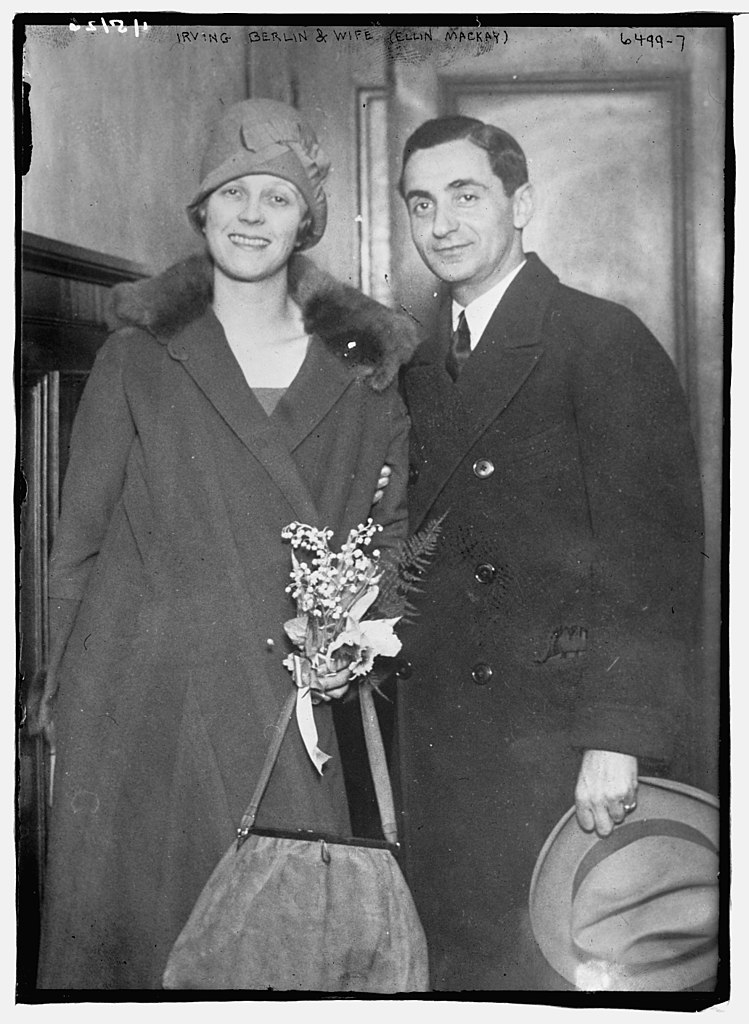

Berlin met the love of his life, the Irish Catholic Ellin Mackay, when she was 21 and he was 36. Clarence Mackay, her father, a multimillionaire, objected to their marriage and was furious when he found out about it two hours after the fact. In retaliation, he cut her out of her share of his $30 million estate.

Berlin and his wife agreed that their children would be brought up as Jews until the age of 14 or 15, after which they could decide for themselves whether they would practice Judaism or Catholicism. Kaplan neglects to tell us which path they took.

The 1929 stock market crash, ushering in the Great Depression, ruined Berlin. He lost his savings of $5 million, which in current terms would be valued at $70 million. His wife’s trust fund came in handy, but Berlin didn’t really need it. Throughout the bleak 1930s, he was a goldmine of highly profitable songs.

One of his favorites, Cheek to Cheek, lost out to Lullaby of Broadway for the best original song at the 1936 Academy awards ceremony in Hollywood. Kaplan believes he should have won. “Was he robbed? From the vantage point of eight decades on it’s clear that he was. Eighty years on, Lullaby of Broadway is merely a period piece, albeit an irresistible one, while Cheek to Cheek has the snap, crackle and pop of …. immortality.”

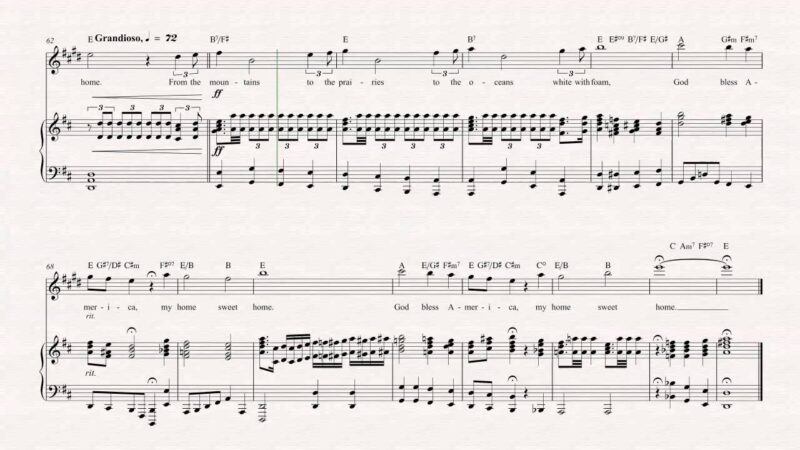

Berlin crafted what is perhaps his most enduring song, God Bless America, in 1938 after the chanteuse Kate Smith asked him to compose a patriotic tune for her weekly radio broadcast. “The reaction was swift and powerful,” says Kaplan. “America loved God Bless America.”

White Christmas, a song he produced for the 1954 movie Holiday Inn, is virtually as peerless. As Kaplan puts it, “What could be stranger than a Jew out of the shtetl and the Lower East Side creating what is arguably the most influential Christmas song of all time?”

Oddly enough, as he points out, the response of film critics to White Christmas was perfunctory. The New York Times mentioned it only in passing in its review and Variety ignored it altogether.

Berlin did not always strike gold. Irving Berlin’s There’s No Show Business Like Show Business was a box-office bomb, as was Mr. President.

From his mid-60s onward, Berlin suffered from severe bouts of depression which required hospitalization. In his 70th year, he did not publish a single song, the first time this had happened since 1907.

During his retirement, he was still busy, tending to his unrivalled portfolio of songs and his real estate holdings. As he became older, he faded from view and grew grump. While on walks, he refused to reciprocate the greetings of neighbors.

He died about five months after the passing of his beloved wife. When an Associated Press reporter asked a family member whether he had been ill, she replied, “No. He was 101 years old. He just fell asleep.”