Thirty years ago yesterday, Iraq invaded Kuwait, sparking an international crisis that culminated with the first Gulf War.

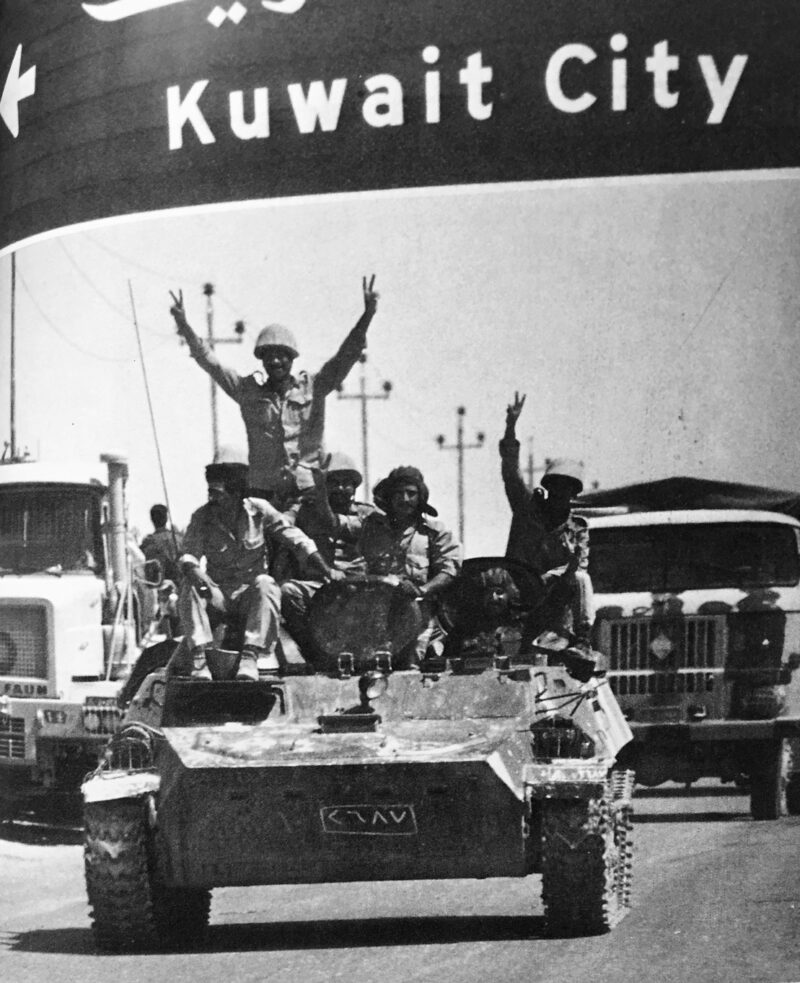

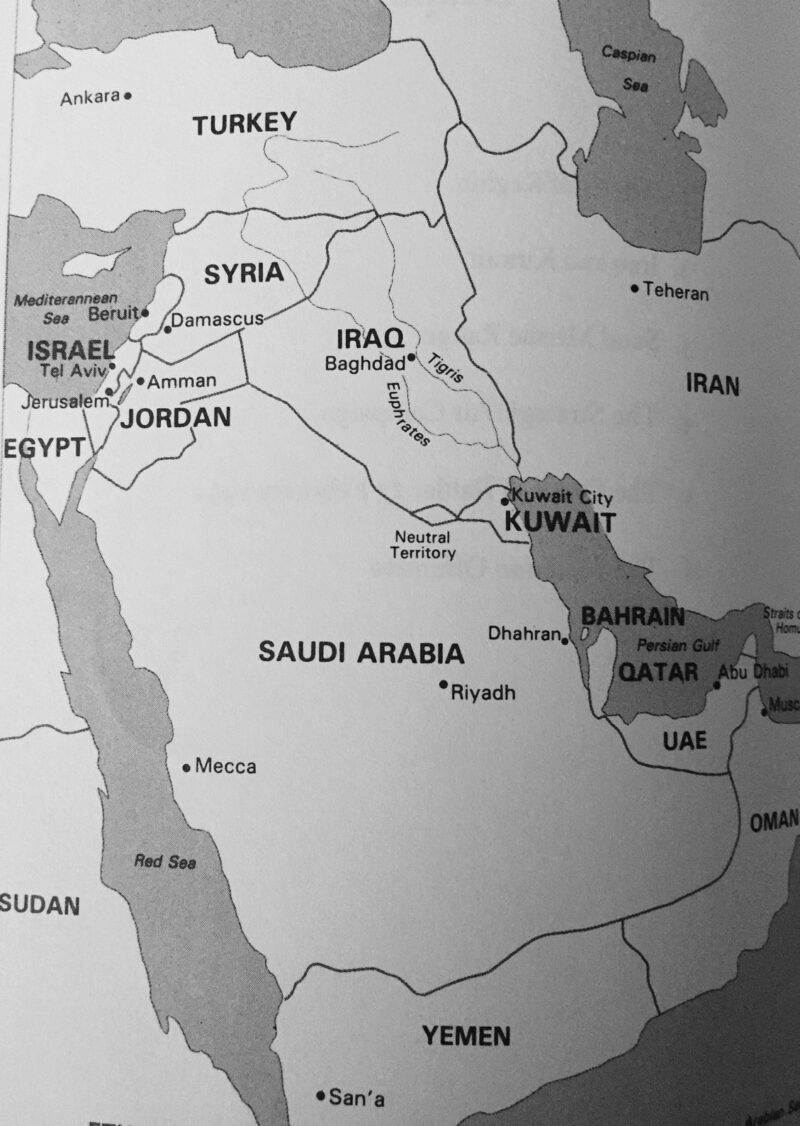

On August 2, 1990, 120,000 Iraqi troops, spearheaded by an armored force of hundreds of tanks, thundered into Kuwait in a universally condemned invasion. In one fell stroke, Iraqi President Saddam Hussein gained control of 20 percent of the world’s oil reserves and a coastline on the Persian Gulf.

He thought he could get away with it, but he erred, in what turned out to be the mother of miscalculations.

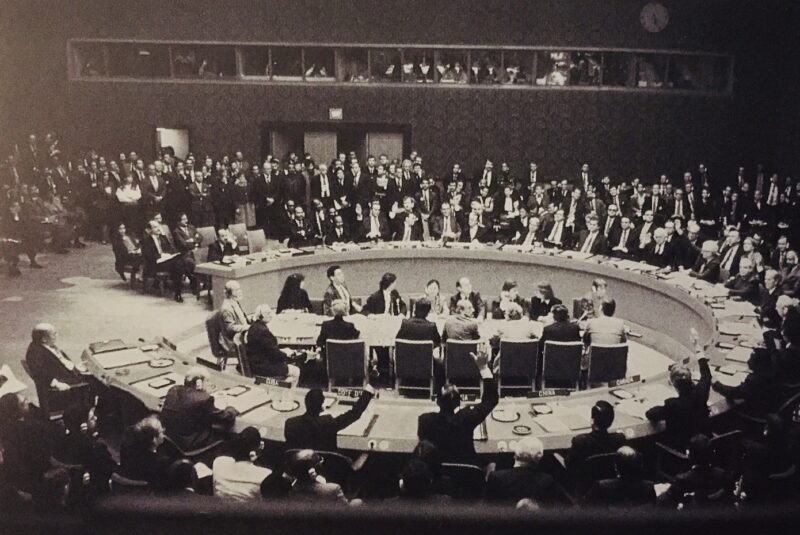

The United Nations Security Council demanded Iraq’s “immediate and unconditional” withdrawal. The United States sent troops to bolster the defences of its long-time ally, Saudi Arabia.

Brazenly ignoring the condemnations of the major powers and its regional neighbors, Iraq poured an additional 200,000 troops into Kuwait, annexed it and declared it its 19th province.

Saddam would pay a heavy price for his unbridled aggression.

UN sanctions isolated and crippled Iraq, one of the wealthiest and most powerful countries in the Arab world. And in January 1991, in Operation Desert Shield, the United States and its allies launched a barrage of air strikes against Iraq. This was followed a month later by Operation Desert Storm, a ground invasion of Kuwait and Iraq that forced Iraq to retreat and end its occupation of Kuwait.

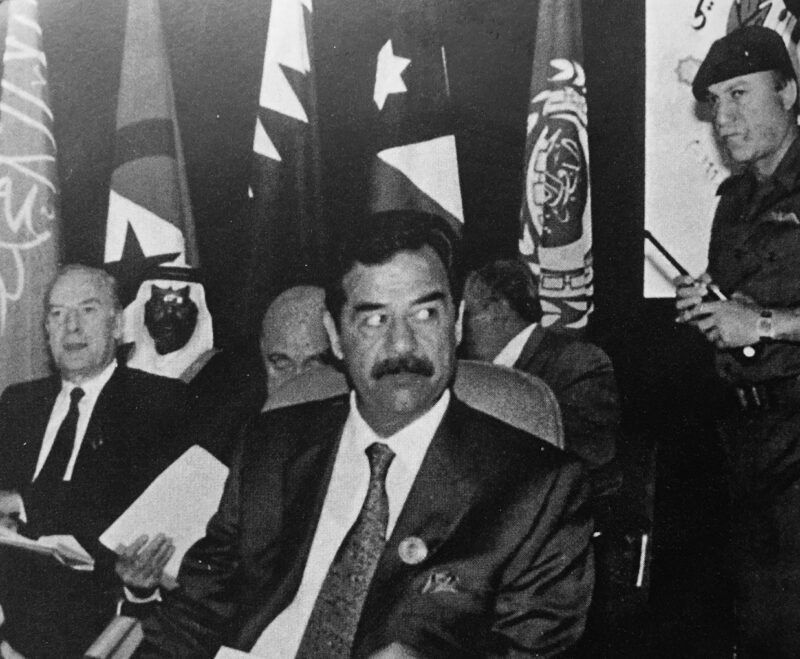

Saddam’s decision to invade Kuwait was surprising.

Iraq, having fought an eight-year war with Iran that basically ended in a draw in 1988, was expected to focus on rebuilding itself in the postwar period. But Saddam overreached, much to Iraq’s detriment.

Tensions between Iraq and Kuwait began simmering in the summer of 1990, when Saddam demanded the cancellation of a $14 billion loan it had acquired from the Kuwaiti government to finance the war with Iran. Saddam claimed that Iraq had shed blood and treasure on behalf of Sunni Arabs to keep Iran, a Shi’a power, in check. But his argument had no effect and Kuwait refused to cancel Iraq’s debt.

A border dispute, a bone of contention since Kuwait’s independence from Britain in 1961, caused problems as well. Saddam claimed the British had expropriated land from Iraq to carve out Kuwait.

Saddam accused Kuwait of stealing oil from its Rumalia oil field and demanded compensation. Kuwait, a U.S. ally, denied this accusation and claimed that Iraq had illegally drilled for oil on its soil. Arab League mediators, to no avail, tried to defuse the conflict. Iraq’s talks with Kuwait were suspended on August 1.

A few days before the collapse of these negotiations, the U.S. ambassador to Iraq, April Glaspie, met Saddam in Baghdad. Until that point, the United States had fairly cordial relations with the Iraqi regime, having tilted toward Iraq during its protracted war with Iran.

By all accounts, Glaspie told Saddam that the United States had no opinion about Iraq’s border dispute with Kuwait. Saddam reportedly regarded her comment as a green light to invade Kuwait. But in an appearance before the U.S. Senate Foreign Relations Committee in Washington in March of 1991, Glaspie insisted she had warned Saddam to stay clear of Kuwait.

Iraq required only two days to occupy Kuwait. The small Kuwaiti army had no realistic chance of repelling the Iraqis. Kuwait’s ruler, Prince Jaber al-Ahmed al-Sabbah, fled to Saudi Arabia. His brother was killed by Iraqi troops.

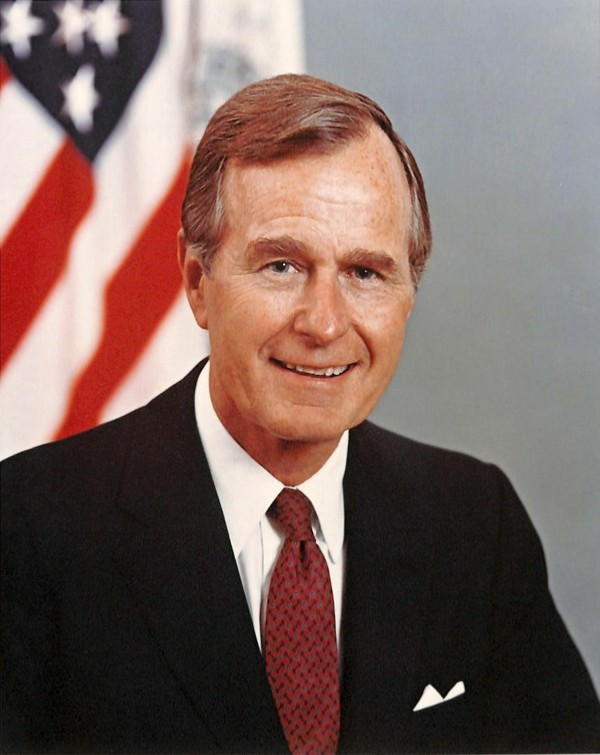

On August 6, the UN Security Council imposed a financial, trade and military embargo on Iraq. Forty eight hours later, following Iraqi threats to invade Saudi Arabia, U.S. President George H.W. Bush announced that American troops under the command of General Norman Schwarzkopf would be dispatched to the kingdom.

Some Saudis, like Osama bin Laden, the future leader of Al-Qaida, vehemently opposed the presence of an “infidel” army in the heartland of Islam.

Iraq, on August 8, announced that its annexation of Kuwait was “complete and irreversible.”

The United States, in the meantime, was in the process of assembling a coalition of 32 European, Arab and Asian nations to eject Iraq from Kuwait.

As the crisis deepened, the UN Security Council on November 29 passed a landmark resolution authorizing member states to use “all necessary means” against Iraq if it failed to withdraw from Kuwait by January 15, 1991.

Several days before the deadline, U.S. Secretary of State James Baker and Iraqi Foreign Minister Tariq Aziz met in Geneva in a last-ditch, but vain, attempt to break the impasse.

On January 17, the first Gulf War broke out after the United States and its allies bombed Iraq in what would be an intense air campaign. Iraq responded by firing Scud missiles at Israel and Saudi Arabia. Iraq launched 39 Scuds at Israel, causing some property damage and killing a handful of Israelis.

Israel wanted to retaliate, but Bush prevailed upon Israeli Prime Minister Yitzhak Shamir to exercise restraint, knowing full well that Israel’s involvement in the hostilities could impel Arab states like Syria and Egypt to leave the coalition and thereby tear it asunder.

The Israeli government reluctantly complied with the American request. The United States deployed Patriot missile batteries and their crews in Israel to intercept incoming Scuds. Their effectiveness was at best questionable.

Throughout the war, Saddam offered to withdraw from Kuwait in exchange for Israel’s withdrawal from the occupied territories. It was an ill-disguised attempt to curry favor with Arab states and the Palestinians and to destroy the coalition.

The U.S. ground attack in Iraq started on February 24 and ended 100 hours later with the defeat of the Iraqi armed forces and the liberation of Kuwait.

Toward the close of the war, Bush urged the Shi’a population of Iraq to stage a rebellion against Saddam, but he did not provide logistical support and the Iraqi regime mercilessly crushed the uprising. Bush, however, helped Kurds in northern Iraq to establish a semi-autonomous enclave by means of a no-fly zone.

Iraq left Kuwait in a parlous state, having plundered it and caused an ecological disaster after setting 750 oil wells on fire.

One hundred and forty eight American soldiers died in Operation Desert Storm and a further 100 troops from allied nations were killed in Iraq and Kuwait.

UN sanctions against the Iraqi government remained in place after the war, leaving Iraq greatly weakened and its people is great distress. By one estimate, 100,000 Iraqi civilians died in the crossfire or succumbed to malnutrition and disease.

In the wake of the war, the Bush administration pushed for a resolution of Israel’s conflict with the Palestinians, pressuring Israel to withdraw from the West Bank and the Gaza Strip and to end its settlement project there.

Washington’s signature achievement was the convening of the Madrid peace conference, but it was little more than a glorified photo op.

Saddam continued to rule Iraq with an iron fist for the next 12 years, but the regional dominance he had once enjoyed was a thing of the past. His tyrannical regime would survive for only the first three years of the 21st century.

The second Gulf War erupted in 2003, flushing Saddam and his Baathist Party apparatus into the bowels of history for once and for all.