Of all the crimes perpetrated by the Nazis before and during World War II, the wanton theft of Jewish-owned books is probably the least known.

Under the direction of Adolf Hitler’s fascist regime, Nazi thieves plundered millions of books in Germany and throughout Europe, in what was “the largest and most extensive book-looting campaign in history,” writes Mark Glickman in Stolen Words: The Nazi Plunder of Books, published by The Jewish Publication Society of America in conjunction with the University of Nebraska Press.

“The Nazi pillage of Jewish books was an assault on the very core of Jewish life,” says Glickman.

Of course, Nazi Germany was not the first oppressor of Jews to resort to this tactic. As he points out, the first recorded incident of Jewish book destruction dates back to the second century BCE, when the Seleucid emperor, Antiochis IV, ordered the shredding and burning of Jewish books during the Macccabean revolt in the Land of Israel.

In 681, a church synod, the Twelfth Council of Toledo, burned Talmuds in Spain, assuming they contained blasphemous anti-Christian content. In 1239, Pope Gregory IX issued an order to confiscate all copies of the Talmud. Several years later, thousands of Talmuds in France were burned. In 1553, Pope Julius III decreed that Talmuds in Italy, a center of the Jewish publishing industry, should be burned. And so it went in Germany, Poland, Russia and elsewhere.

On occasion, Jewish books were censored rather than thrown into the flames. For Jews, censorship was a far better option, enabling them to save their books.

Before assuming power, the Nazi Party denounced “un-German” authors and publishers. And on the day Hitler was sworn into office as chancellor on January 30, 1933, the SS paramilitary police raided bookshops and publishing houses to cleanse the country of undesirable books.

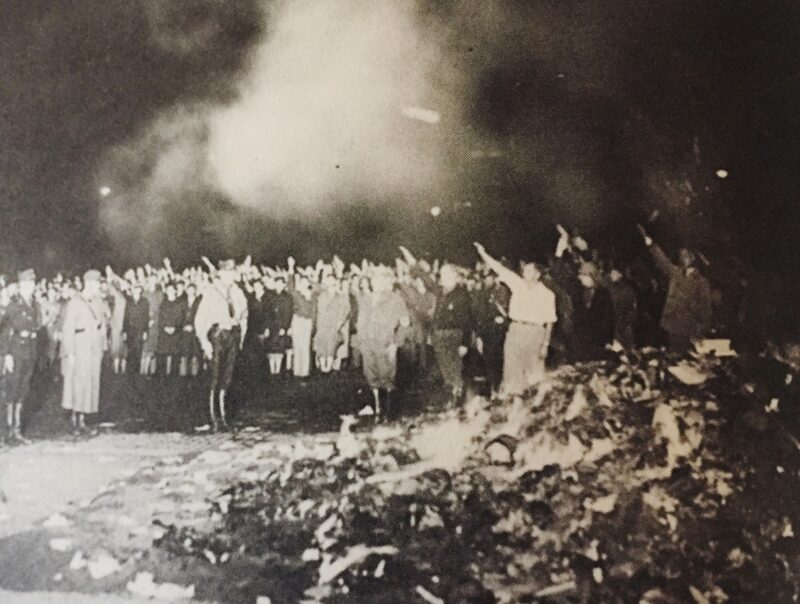

On May 10 of that fateful year, the regime organized book burnings throughout the nation. What the German Jewish poet Heinrich Heine wrote in 1882 would come to pass: “Where men burn books, they will also burn people in the end.”

These thuggish spectacles eventually petered out, and incineration was replaced by preservation.

Belatedly enough, Nazi intellectuals came to the realization that if they were to truly understand Jews, the eternal enemy, they needed to study Jewish texts.

“The Nazis devoted so much attention to Jewish books because Germans were a bookish people, and they understood the importance of the printed word to cultural identity and ethnic pride,” says Glickman.

The economic historian Peter-Heinz Seraphim was one of the first to grasp this idea. Prior to writing The Jews of Eastern Europe (1938), which posited the theory that Jews were intent on dominating the world, he visited the Yiddish Scientific Institute (YIVO) in Vilna to finish his research. Seraphim’s book, which drew heavily on the work of Jewish historians, established him as one of Germany’s foremost experts on Jews and Judaism. In 1941, he wrote articles calling for the mass deportation of Jews from Europe.

Another historian who used his knowledge of Jewish texts to defame Jews was Gerhard Kittel, the son of an Old Testament scholar. In accordance with Nazi doctrine, he believed that Jews and Christians should be separated to preserve Aryan purity.

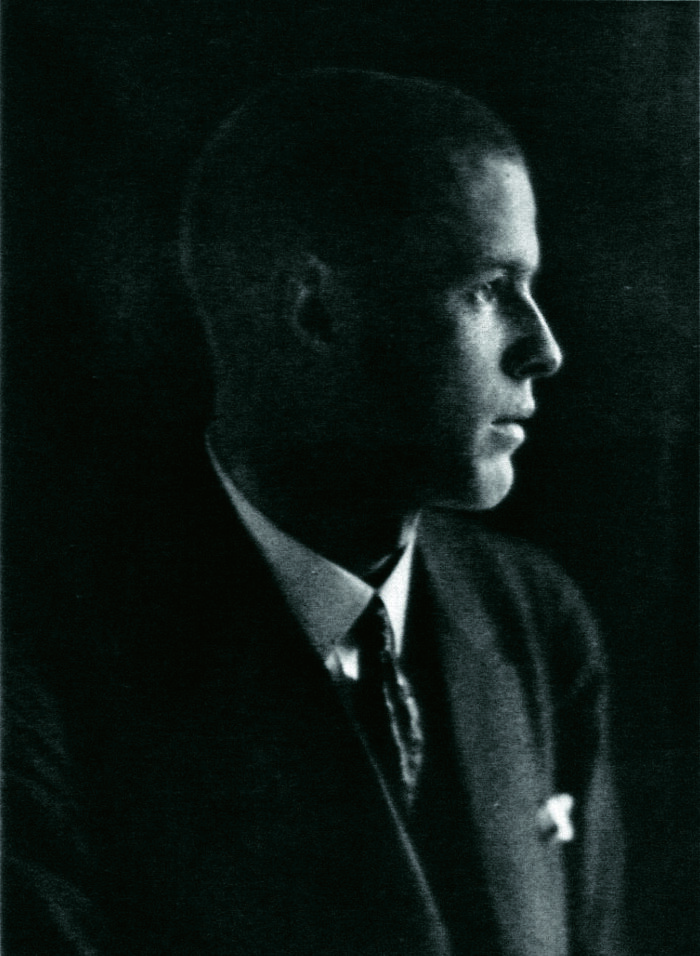

Within the regime itself, the top-ranking official who encouraged scholars like Seraphim and Kittel was Alfred Rosenberg, the head of the Nazi Party’s Office on Foreign Relations and then, following Germany’s invasion of the Soviet Union in June 1941, the minister for the occupied eastern territories.

Like Hitler, Rosenberg believed in the importance of developing a scientific justification for Nazi racism and antisemitism. It was therefore necessary to build institutes to formalize the study of Jews and Judaism. One of the first was the Reich Institute for the New Germany, whose director, Walter Frank, wrote his PhD dissertation on Adolf Stocker, an Austrian antisemitic theorist.

Another Nazi think tank was the Research Department for the Jewish Question. At its grand opening in Munich in 1936, the guest speaker was Karl Alexander von Muller, the president of the Bavarian Academy of Sciences. In the first official hint of the coming Nazi pillage of books, he outlined his vision of a grand Jewish library as a weapon to combat Jews. His concept was embraced by, among others, Walter Grundmann of the Institute for the Study of Jewish Influence on German Church Life.

By 1941, the Nazis were eying the 350,000 volumes of the Judaica collection of Frankfurt’s municipal library, the world’s largest.

Heinrich Himmler, the head of the SS, was also interested in amassing Jewish books for evil ends. He delegated his deputy, Reinhard Heydrich, to create an academic department dedicated to proving the existence of an international Jewish conspiracy. Heydrich appointed Franz Alfred Six, a graduate of Heidelberg University, as its director.

Regarding his task as a crucial element of Nazi ideological warfare, Six knew that his understanding of the “Jewish menace” would require him and his cohorts to acquire knowledge of Jewish history, culture and philosophy, all of which could be found in Jewish libraries.

Germany began its looting spree following its conquest of Poland. The books and materials Six and his accomplices gathered from libraries, schools, synagogues, museums and private collectors provided the Nazis with invaluable information about Jewish communities and helped them carry out their genocidal plan to murder Polish Jews on an industrial scale.

By Glickman’s accounting, the Nazis looted more than 100 libraries in Poland, stealing more than one million books, 600,000 from the city of Lodz alone.

Having invaded France, Holland and Greece, the Germans raided private homes and museums in search of books, paintings and other cultural treasures, a methodical process Glickman describes at length.

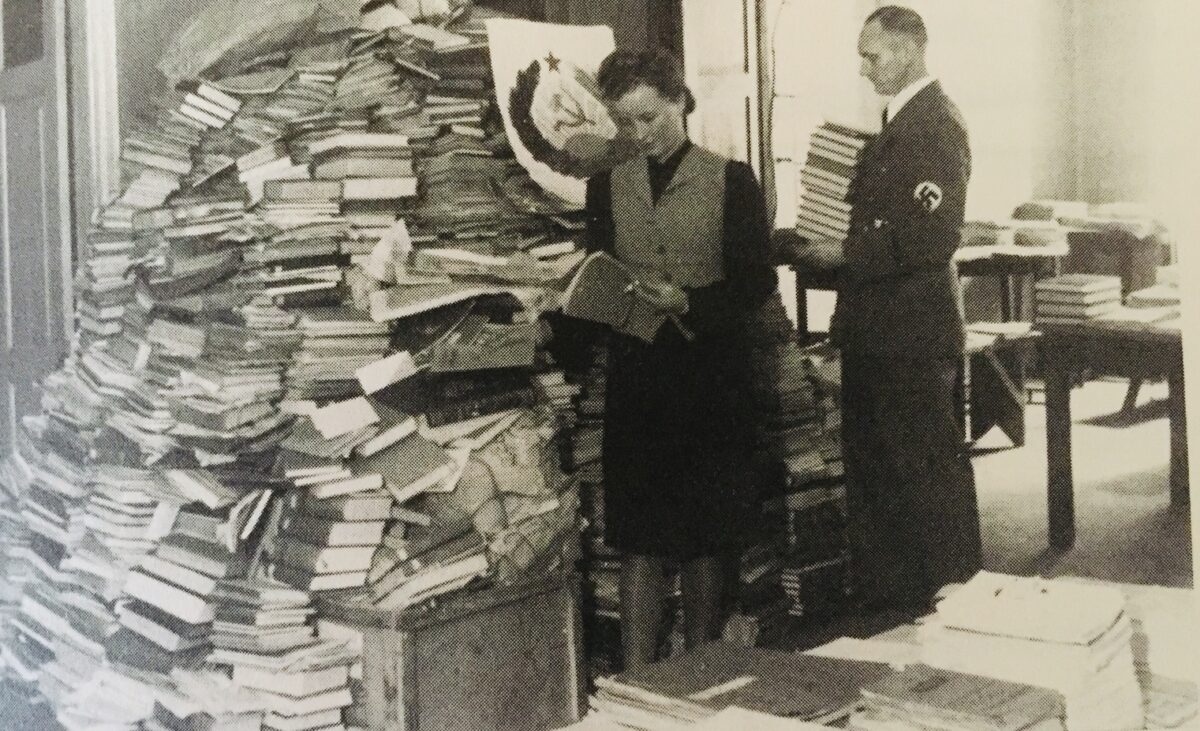

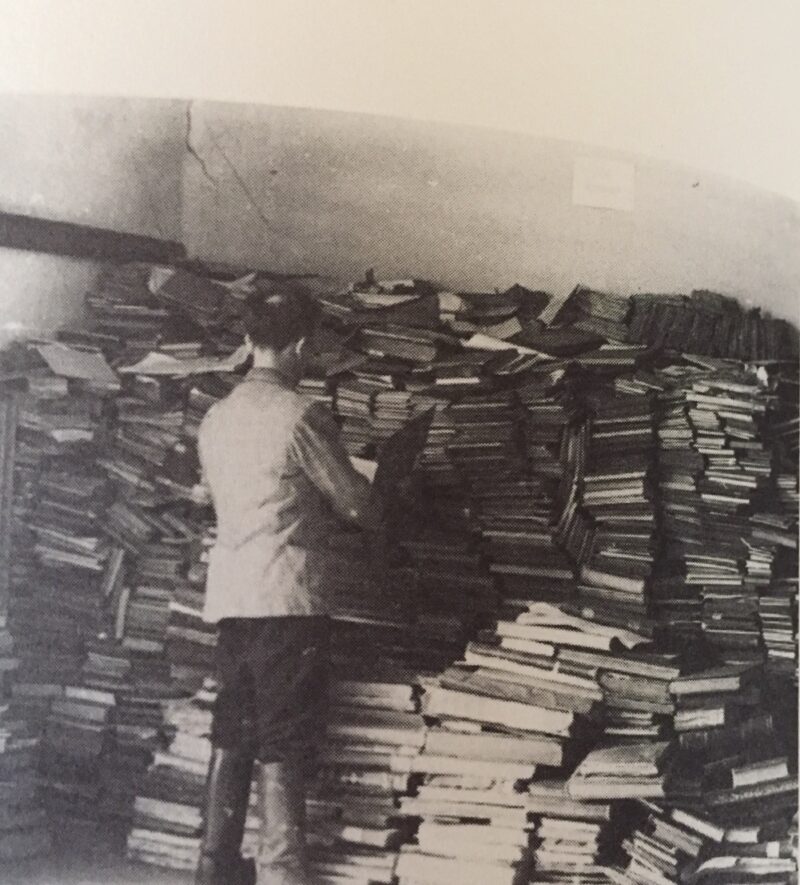

“Teams of looters would go into newly conquered towns t0o collect all the Jewish books they could find,” he says. “Often with the help of Jewish conscripts, they would sort through material to select what was most valuable and destroy the rest.”

In at least two instances, the looters were thwarted. Jewish workers in Vilna managed to save some books. And in Sarajevo, a Muslim librarian named Dervis Korkut managed to conceal a priceless illuminated 12th century haggadah on bleached calfskin that the Bosnian National Museum had purchased from a Jewish man in 1894.

After Germany’s defeat, the United States made immense efforts to find the cultural treasures the Nazis had looted and placed in storage in castles, salt mines and special depots. The mission was spearheaded by the Monuments, Fine Arts and Archives program, which was staffed by American soldiers who had been trained as historians, artists, archivists, conservators and curators.

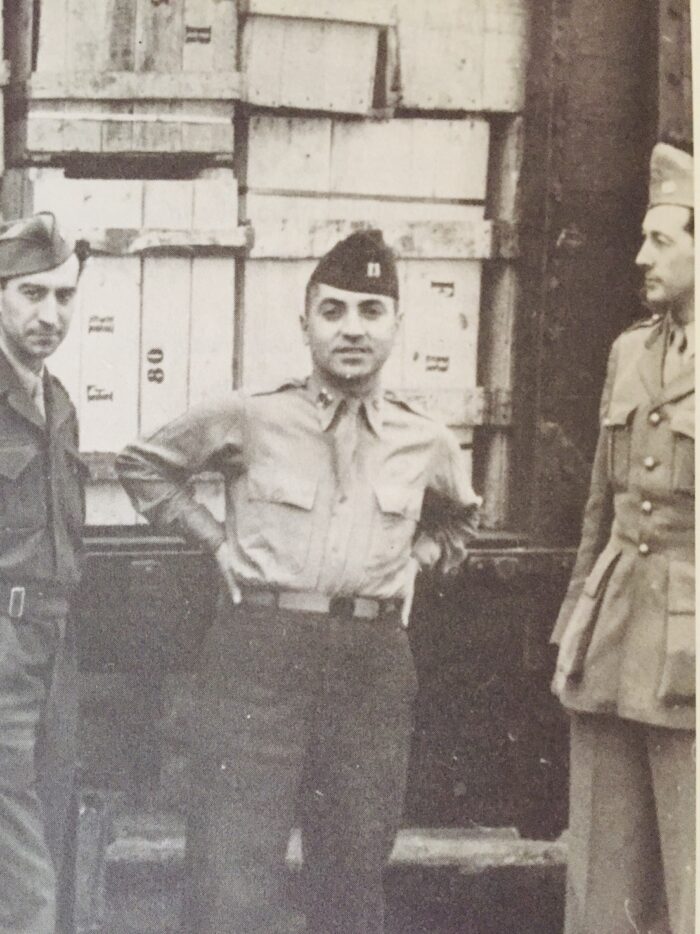

Although the unit was mostly interested in salvaging great works of art, it allocated personnel to finding and returning books to their rightful owners. Captain Seymour Pomrenze, who was born in Kiev, led the effort to sort out the books, which were stacked in piles at a special depot in Offenbach, Germany.

He and his staff estimated that there were more than one million books and other items in the depot, according to Glickman. By the end of 1946, they had been returned to more than a dozen countries, including Russia, Italy and Belgium.

Another organization, Jewish Cultural Reconstruction, focused on sending unclaimed books to libraries in Israel, the United States, Britain and an assortment of other nations.

Glickman, an American rabbi, tells this story with skill and authority.