Israel’s image on the political Left has been increasingly tarnished since the 1967 Six Day War, which utterly transformed the Arab-Israeli conflict.

Once embraced by most progressives as a shining light of democracy in a dark region of despotism, Israel was repudiated by leftists as a colonialist, racist state, while its adversary, the Palestinians, were anointed as revolutionary anti-imperialist freedom fighters.

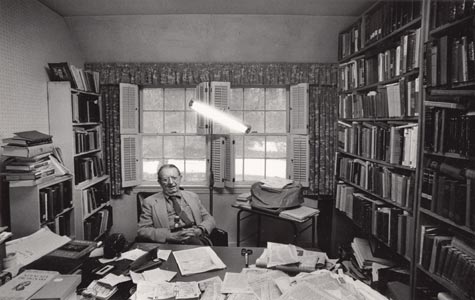

Susie Linfield, an American journalist and liberal supporter of Israel, analyzes this stunning metamorphosis in The Lion’s Den: Zionism and the Left From Hannah Arendt to Noam Chomsky, published by Yale University Press.

By examining the ideas of eight 20th century intellectuals who struggled with the philosophy of Zionism and then with Israel’s existence as a Jewish state striving to establish itself in a hostile environment, she explains how Israel is often perceived in left-wing circles. She thinks this transformation occurred as the Left moved to define itself from anti-fascist to anti-imperialist.

As she explains in the introduction, she was impelled to write this thoughtful book from a sense of double grief.

“First, I am grieved by the contemporary Left’s blanket hatred of Israel” and of its “idealization, misrepresentation and distortion of the Palestinian national movement.” Linfield is also appalled that Israel’s very existence is questioned and/or rejected by advocates of a one-state solution, which she brands as “ethnocide.”

“Second, I am grieved by the trajectory of contemporary Israel, by which I mean the decades-long occupation, the denial of Palestinian rights to land, suffrage, the rule of law, and sovereignty, and the violence that the occupation’s maintenance has inevitably dictated. I am equally grieved by the occupation’s noxious offspring within Israel itself: chauvinism, religious fundamentalism, intolerance, attacks on democratic freedoms, and sheer racism.”

Linfield draws compelling pen portraits of two European Jews, the philosopher Hannah Arendt and the journalist/novelist Arthur Koestler. She delves into the lives of four socialists, Maxime Rodinson, Isaac Deutscher, Albert Memmi and Fred Halliday, the only non-Jew in the group. And she produces biographical sketches of two Americans, I.F. Stone and Noam Chomsky.

“When we study the history of the Left and Israel, we study the twentieth century’s knottiest dilemmas,” she writes in a reference to democracy, nationalism, socialism, the morality of violence, racism, antisemitism, secularism, colonialism, self-determination, and justice. “When we talk about Israel, we talk about the very nature of modernity and the often catastrophic history of the past century, which continues to define our world.”

Arendt, forced out of Germany by the Nazis, settled in the United States. Best known for two books, The Origins of Totalitarianism and Eichmann in Jerusalem, her writings on Zionism and Israel are often cited by leftist proponents of a binational state in place of Israel.

Arendt’s attitude toward Zionism and Jewish statehood was contradictory. Introduced to politics through Zionism and to Zionism through German fascism, she was skeptical of Jewish political sovereignty and opposed the partition of Palestine. Yet she supported the Jewish right to Palestine, argued in favor of a Jewish army to defend Palestinian Jews, and rallied behind Israel in the 1967 and 1973 Arab-Israeli wars.

From 1933 to 1948, she regarded Zionism as the liberation movement of the Jewish people and hailed Zionist accomplishments in Palestine. But she derided Theodor Herzl, the founder of the modern Zionist movement, as a “crackpot” and railed against the establishment of Jewish statehood because it was supposedly impossible and unjust.

Arendt alternately called for a Palestinian-Arab-Jewish federation, a United Nations protectorate, a pan-Arab-Israel commonwealth, and a Mediterranean and British commonwealth. Arendt’s advocacy of non-sovereignty, Linfield says scornfully, was “equivalent to surrender.”

Arendt’s beliefs were based on the erroneous assumption that an anti-national world was imminent, and that Palestinian Arabs were partial to binationalism. The pre-1948 Palestinian national movement had “sold itself to German and Italian imperialism” and was “thoroughly fascist-infiltrated,” she noted.

Linfield is critical of Arendt, saying her judgments during that pre-state period were “deeply, radically perplexingly wrong.”

According to Linfield, Arendt stopped writing about Israel after 1950, though she often visited relatives there. She resumed her monologue with Israel after covering the trial of Nazi war criminal Adolf Eichmann in Jerusalem.

Linfield has mixed feelings about Eichmann in Jerusalem, which was published in 1963. Astute, forceful and moving at times, it was “infuriating, wrong-headed and odious” as well, oozing with contempt for Zionism, Israel, the Israeli leadership and Holocaust survivors.

Nevertheless, she supported Israel when it was at war. “Her relationship to Israel was like that of an alienated, rebellious child to her family,” says Linfield, who argues that Arendt’s ambivalence about Israel signifies that she never really worked through her feelings about Zionism.

Koestler, a man of deep contradictions, was at times a fiercely committed right-wing Zionist and a Communist. An acolyte of Vladimir Jabotinsky, the Zionist Revisionist icon, he settled in Palestine in 1925 and lived there for the next four years. Although he was totally urban in his outlook, he joined a left-wing rural commune, which eventually asked him to leave.

A freelance journalist who contributed articles on Palestinian life and politics to European newspapers, he finagled a job as Middle East correspondent for a German daily at the tender age of 22. He moved to Berlin in 1930, and in the following year, he joined the Communist Party in Germany.

In 1937, he returned to Palestine as a reporter for a British newspaper. Koestler believed that the partition of Palestine into Jewish and Arab enclaves already had occurred in practical terms. “The two communities seem to live on different planets,” he wrote in a perceptive dispatch. “There is no common ground between them. Their national aspirations are incompatible.”

Koestler left the Communist Party in 1938 and devoted himself to Jewish and Zionist causes. By now, he viewed a Jewish state as a necessity rather than as an idealistic project. In the late 1940s, he wrote two major books about Palestine: Promise and Fulfillment, an account of Zionism under the British Mandate, and Thieves in the Night, a novel. Some years would elapse before his anti-Stalinist novel, Darkness At Noon, appeared.

He never forgave Britain for having created “a second Ireland in the Levant” by virtue of its unilateral withdrawal from Palestine.

Maxime Rodinson was born in Paris into a secular, anti-Zionist Russian Jewish working-class family. He became an Orientalist, a scholar of Islam and the Middle East whose works included Islam and Capitalism and Marxism and the Muslim World. He joined the French Communist Party in 1937.

Before Germany’s invasion of France in 1940, the government sent him to Beirut under its auxiliary military program. During the war, he was a teacher at the French Institute of Arab Studies in Damascus. His parents were murdered in Auschwitz. Returning to Paris in 1947, he carved out a career as an academic, while establishing himself as one of the leading critics of Zionism.

Rodinson set out his views comprehensively in the magazine Les Temps Modernes in the aftermath of the Six Day War. Although he indicted Israel as a colonial settler state, he conceded that the pre-1948 Zionist movement had acquired land legally and had not exploited Arab labor. He acknowledged that the Zionists’ search for support from imperialist states was no different than the Arab nationalist movements’ quest for international backing.

Nonetheless, he concluded that Israel’s creation was an “outrage” against the Arabs. Describing Israel as an “alien body” created by “foreigners” for the benefit of foreigners, he claimed that it regenerated antisemitism in the Arab world and pulled Jews away from universalist traditions. To Rodinson, the Arabs’ non-acceptance of Israel was “perfectly grounded in rationality and ethics.” Yet, like Arendt, he recognized Israel’s achievements and regarded it as “virile, modern and forward-looking.”

Consistently opposed to a one-state solution, he dismissed it as a non-starter and argued that the Palestinians’ “right of return” doctrine was a mirage. “One can only speak in terms of the coexistence of two states,” he declared.

Though he did not believe in the reality of a Jewish people, he was convinced that the Israelis had formed a “new nationality with a culture of its own. The Israelis were not “a heterogeneous collection of gangs of occupiers who could be sent back where they came from.”

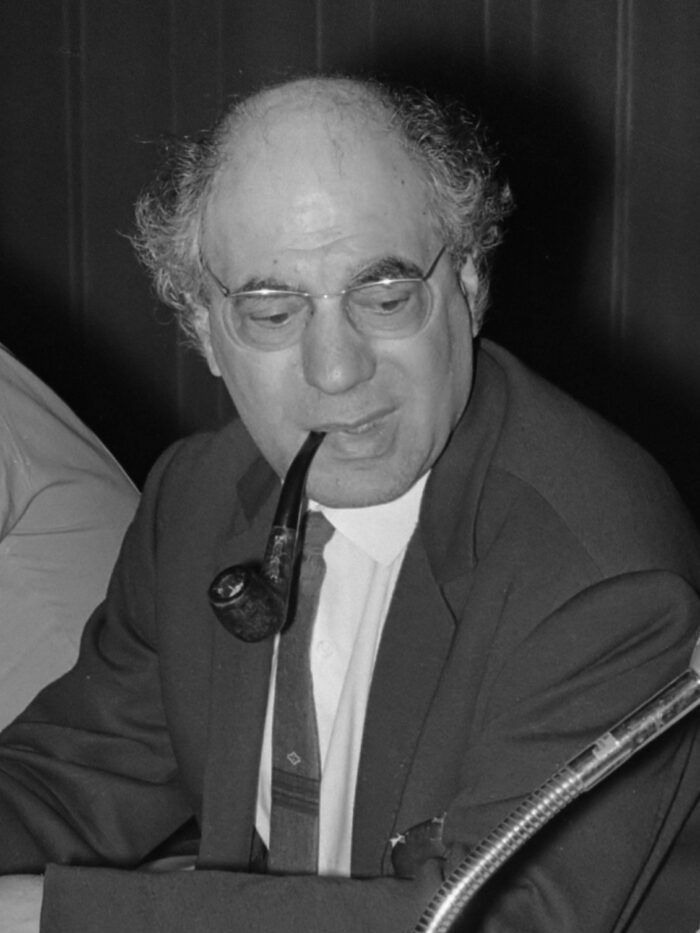

Deutscher, a Polish Jew whose father was a printer of Hebrew religious literature, sympathized with and even admired Israel, despite his ideological aversion to it. Nor did he equate atheism and socialism with a rejection of Jewish culture.

He joined the outlawed Polish Communist Party in 1925, and settled in Britain in 1939. Like Rodinson, he avoided the Holocaust by leaving his birthplace. He learned English well enough to write for the Economist and the Observer

He coined the now common phrase “non-Jewish Jew” in a speech to the World Jewish Congress in 1958. A non-Jewish Jew was a renegade who was spiritually Jewish.

Visiting Israel in 1954, Deutscher was impressed by its egalitarian spirit and network of kibbutzim. He returned four years later and documented its “record of great achievement.” He believed that Jews needed a territorial refuge, but denounced Zionism and contended that Israel could not exist indefinitely in a sea of Arab hostility. He maintained that Israel had done far too little to pursue peace with the Arabs, though he defended the Arabs’ refusal to recognize Israel.

He admonished Israel for resting on the glib assumption that lasting security could be attained by military victories. He rejected the Arab strategy of destroying Israel as impractical and immoral, and was disappointed by their failure to launch a progressive revolution.

In short, as Linfield points out, Deutscher “did not believe that Israel was the answer to the Jewish Question, but he knew that the destruction of Israel would be a staggering Jewish calamity. He did not necessarily believe in the Jewish state, but he definitely believed in the Jews.”

Memmi, a Tunisian Jew who studied philosophy at the Sorbonne and was a founding editor of the magazine Jeune Afrique, was a devoted leftist and anti-colonialist who reproached the Left for its inability to understand the nature of Jewish oppression and Zionism.

As Linfield writes, “Memmi turned Rodinson’s anti-Zionism on its head. Whereas Rodinson believed that socialist solidarity negated Zionism, Memmi argued that Zionism, as the national liberation movement of an oppressed people, demanded the Left’s support.

She adds, “Memmi’s adherence to socialism was entwined with his identity as a Jew. In fact, he believed that every Jew … had to be on the Left. As a persecuted people, Jews required a radically transformed world … But there was a problem, and it was large: The Left had betrayed the Jewish people time and time again …”

Leftists, especially New Leftists, were enthralled by Cuban, Vietnamese, Chinese, Algerian and Palestinian nationalism. Yet they loathed Jewish nationalists, or Zionism, as something apart. “This approach would come to fruition in the 1967 Arab-Israeli war,” Linfield says.

Till the end of his days, Memmi defended two overarching principles: the Arab people’s right to independence and national development, and the Jewish people’s right to the same. Memmi was unequivocally pro-Israel, but disappointed by its drift away from secularism and socialism.

Fred Halliday, born in Ireland, graduated from Oxford, studied at the School of Oriental and African Studies, worked as an editor at the New Left Review, and taught at the London School of Economics.

By any measure, he was remarkably balanced in his opinions.

He condemned Israel’s post-1967 occupation of the West Bank and the Gaza trip and criticized its denial of Palestinian statehood as short-sighted and arrogant. But he criticized the Left for ignoring, excusing or supporting Palestinian terrorism and Arab religious fanaticism. He regarded “triumphalist, intransigent nationalism” in Israel with distaste, but was appalled by the often chauvinistic nationalism in Arab societies. He told the leader of the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine that Israelis constitute a legitimate nation and informed a high-ranking Hezbollah official that its use of Koranic verses to denounce Jews was racist.

Halliday chided the Left’s cherished notion of replacing Israel with a secular, democratic Palestine as nothing less than a fantasy, and promoted the two-state solution as eminently realistic.

Isidor Feinstein, otherwise known as I.F. Stone, changed his surname in 1937 due to his fear that antisemitism in the United States was on the upswing. As a journalist, he worked for, among other publications, the New York Post and the New Republic. Finding himself unemployed in 1952, he founded I.F. Stone’s Weekly, which battled McCarthyism, U.S. involvement in the Vietnam war and government corruption.

Stone was a supporter of the United Nations’ 1947 Palestine partition plan, but switched sides when he temporarily endorsed the formation of a binational state, where, he believed, Holocaust survivors should be resettled. His advocacy of Jewish immigration led to his 1946 classic work, Underground to Palestine. Linfield calls his second book, This is Israel, “one of the most pro-Zionist books ever written.”

His commitment to Zionism was a logical extension of his leftist principles, but his relationship with Israel was stormy. “Stone was devoted to a thriving Israel and to the Jewish people’s survival, but he was also genuinely tormented by the suffering of the Palestinian refugees,” says Linfield.

While Stone believed that their resettlement in Israel was out of the question, he held Israel and the Diaspora responsible for the well-being of the refugees.

Stone backed Israel’s 1956 invasion of the Sinai Peninsula, but quickly withdrew his support on the grounds that preemptive aggression was unacceptable. Analyzing Stone’s wildly-changing positions, Linfield writes, “He was torn between defending Israel’s security against unrelenting hostility, upholding the international rule of law, and respecting Arab self-determination.”

Although he was relieved by Israel’s victory in the Six Day War, he believed that the key to its survival was amity with its Arab neighbors. Incredibly enough, he advised Israel to return to the 1947 partition plan. In a harsh essay in the New York Review of Books, he assailed the very idea of Jewish sovereignty, which he had fervently championed. He referred to Israel henceforth as a “racial and exclusionist” state.

In Linfield’s judgment, Stone never stopped loving Israel, but he failed “to comprehend the Israelis’ sense of vulnerability, grief, distrust and fear, all of which flourished alongside their military power.”

Chomsky, a renowned linguist, began addressing the Arab-Israeli dispute publicly in 1969, but his connection with Israel was far deeper. Despite his view that the establishment of Israel had been a “tragedy,” he went to live on a left-wing kibbutz in 1953. He planned to return after earning a PhD, but decided not to do so for professional reasons.

For decades, he believed that a majority-Jewish state was by definition undemocratic, claiming that Israel’s existence was based on “the principle of discrimination.” Yet he endorsed the Zionist credo that Jews are entitled to a national home.

Dismissive of a one-state solution, he contended that a secular, democratic state would be neither. “What (the Palestinians) have in mind is an Arab state,” he asserted.

Chomsky argued that Israel’s occupation, combined with Palestinian terrorism, might destroy Israeli democracy. And he warned that American Jews who supported settlements and rejected Palestinian statehood were, in fact, Israel’s enemies. “All these warnings were … prescient,” writes Linfield. “They have been Chomsky’s main contributions to the debate. It is more than too bad that they were not heeded.”

Linfield, however, is hardly one of his admirers.

“Chomsky has always insisted that he cares about Israel’s continued existence. I think this is genuine, though it is a kind of care that, buried under a mountain of animus, is difficult to detect.”

As far as she is concerned, his work on the Arab-Israeli dispute is neither “political analysis nor research-based history,” but rather “an expression of wishful thinking about might-have-beens.”

She elaborates: “To mistake one’s fantasies for facts, or one’s hopes for truths, is a dangerous and narcissistic game. Chomsky plays it often. The remarkable ability to see only what he wants makes Chomsky the most unreliable of narrators.”

In the pages to follow, Linfield cites a litany of examples of his tendency to distort facts. And in a scathing dismissal of his analyses, she says,”He cannot see that the Middle East is not Chomskyland.”

Linfield is apologetic for her denunciation: “It is precisely as a left-wing Zionist who hopes that Israel ends the occupation and rejuvenates its humane principles that I say this.”