Seven hundred thousand Jewish immigrants poured into Israel during its first years statehood, straining its relatively limited absorption capacity. Yet immigration was one of the key priorities of Israel’s first prime minister, David Ben-Gurion, after the 1948 War of Liberation.

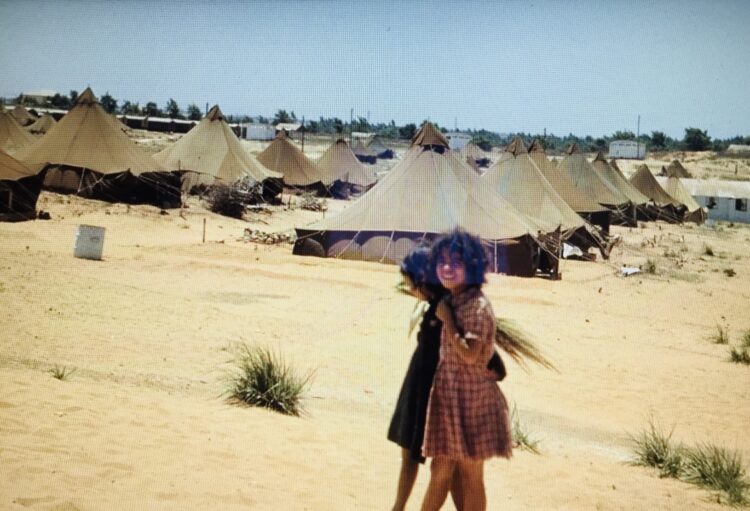

Approximately one-third of the newcomers were sent to abandoned British army bases. These rudimentary transit camps, or ma’abarot, were scattered around the country. By the early 1950s, 90 such camps housed more than 200,000 people, 80 percent of whom were Jews from Arab lands.

The immigrants were accommodated in tents and were provided with food, water and health care. The crowded camps were sealed off by barbed wire, their residents forbidden to leave without permission. More permanent housing was later built to house them. Perceived from the outset as a stop-gap measure, the camps were gradually torn down.

Dina Zvi Riklis paints a vivid picture of this period in Ma’abarot: The Israeli Transit Camps, which will be screened at the online edition of the Toronto Jewish Film Festival, which runs from October 22 to November 1.

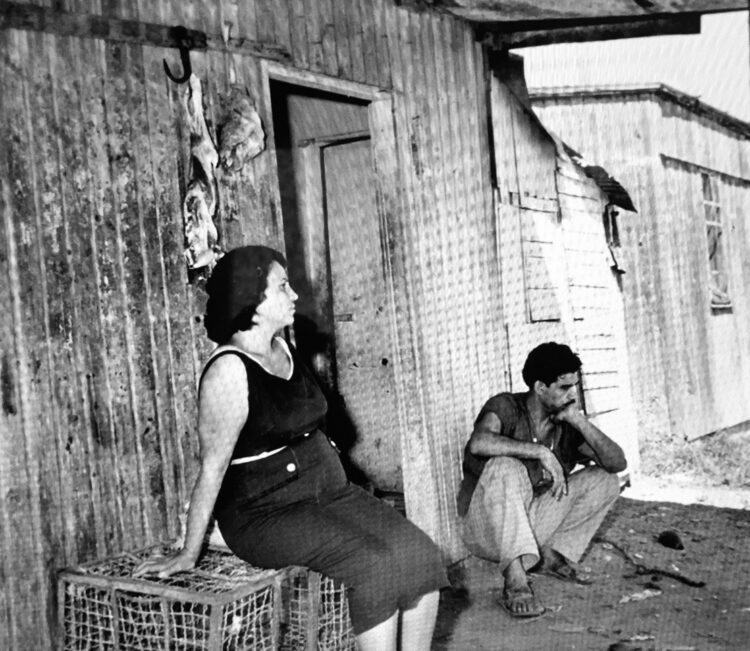

In her documentary, former residents describe their experiences. The spare comments of one man sum up this era. “It was a wretched, poor life, but we survived,” he says.

Some of the new immigrants stayed with relatives until they could manage on their own. Still others, like the Jews of Bulgaria, moved into buildings in Jaffa where Palestinian Arabs had previously lived.

The remainder were placed in transit camps where conditions were difficult. Given their diverse population of European and Middle Eastern Jews, they were Towers of Babel. Since their inhabitants spoke and observed different languages and customs, they hardly mingled and tended to regard each other as strangers. Some Ashkenazi Jews even considered their Sephardi counterparts as backward and primitive.

Although Israel was hard-pressed to absorb these immigrants, Ben-Gurion welcomed still more — 50,000 Yemenite Jews in 1949 and 100,000 Iraqi Jews in 1951.

The influx created fresh problems. In an attempt to defuse growing tensions, the government created public works programs that offered the immigrants a modicum of employment. Iraqi, Polish and Romanian Jews who had been professionals back home became field hands and road builders.

Often, their children had to be bused to schools in distant towns.

The harsh winter of 1950, during which tents were blown away or water-logged, forced Israel to phase out tent encampments and replace them with tin huts. During this interregnum, the government stopped coddling the immigrants and allowed them to look for jobs and stand up on their own feet.

Yet even these advances could not head off the protests that erupted in the camps over high unemployment levels and an assortment of other issues. The protesters were supported by Mapam, the left-wing political party, and the Communist Party.

Throughout these years, Jews from Arab lands often felt they did not receive equal treatment with Ashkenazi Jews. This may well have been true. Top-ranking officials from Ben-Gurion on down believed that Arab Jews were not on the same educational and cultural level as Ashkenazim and needed uplifting.

Objectively, Ashkenazi Jews had several advantages over the Sephardim. They had fewer children, making it easier to purchase affordable flats once they left the camps. And as Holocaust survivors, they were eligible to receive German reparation payments, giving them an extra financial head start.

Israel announced its intention to liquidate the camps in 1952, but about nine years elapsed before the last one was finally closed. This important and usually forgotten footnote of Israeli history is told with authority and empathy by Riklis.