Thousands of young Jewish men and women from all walks of life and countries visit Israel every year free of charge thanks to the Birthright program. Inbar Horesh’s Israeli short film, Birth Right, explores it from a singularly Russian angle.

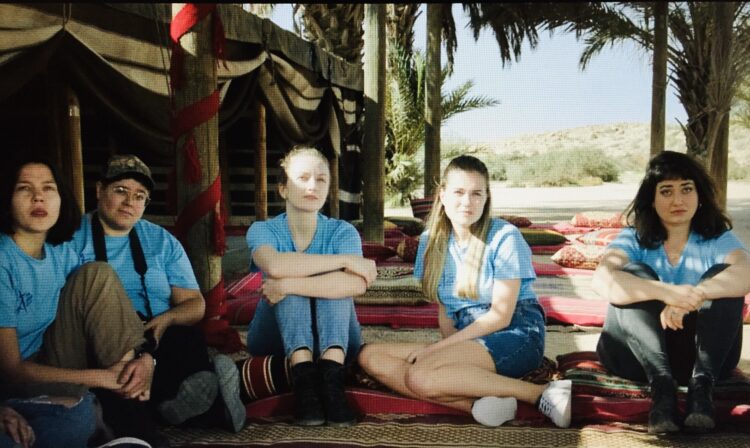

Currently being screened online at the Toronto Jewish Film Festival, it unfolds over the course of a few days as a busload of Russian-speaking visitors tour southern Israel.

The camera pans on several women, but on one, Natasha (Nataliya Olshanskaya), in particular. Twenty one years old, she’s from Moldova, a former republic of the now defunct Soviet Union. Like her companions, she’s in Israel to explore its geography, history and culture and to decide, perhaps, whether she should set down roots and become an Israeli citizen.

Pushing for that outcome, the tour guide exults, “Welcome to your historic homeland” as their bus passes a stretch of arid landscape.

They’re deposited in a camp site in the desert where they will spend the night. Two soldiers in uniform, Ilya and Shlomi, greet them. Ilya, originally from the Russian city of Rostov, is reserved and taciturn. When the guide asks him if he feels a “historical connection” to Israel, he’s at a loss for words. Ilya is not exactly an ambassador for Israel.

Shlomi, a native of the former Soviet republic of Uzbekistan, is far more outgoing, thanking the visitors for having come to Israel.

Unlike the other girls, Natasha plans to remain in Israel after her Birthright trip ends. Speaking to her mother on the phone, Natasha learns that she is not missed at home and that she should stay in Israel.

Having discovered that Natasha’s mother is a Christian, one of her companions informs Natasha that she’s not recognized as a Jew in Israel. This comes as news to Natasha, who’s not as informed about Israel as she should be, considering her intention to be an Israeli.

The scene shifts as Ilya and Shlomi engage in a conversation about the opposite sex. By Shlomi’s estimate, Russian women are easy to seduce.

Before settling in for the evening, the visitors are treated to a camel ride at dusk and a dance party, where Shlomi exhibits his skill as a Don Juan.

In what is the most jarring episode of the film, one of Natasha’s bus acquaintances leaves her uncomfortable and isolated. Taking a walk in the dark to recuperate, she runs into Ilya. As they chat, they both admit they do not like Israel. “I don’t know why I came here,” she says ruefully. “I’m not even Jewish.”

Buoyed by her candor, Ilya opens up and talks about himself and confides in Natasha. His confession draws her close to him.

I don’t know whether the performers are professional actors, but they certainly acquit themselves with aplomb, never striking a false or pretentious note.

Birth Right, which has been making the rounds of Jewish film festivals around the world, is a spare, unsentimental and affecting movie that speaks to the themes of identity and nationalism. It does not wave Israeli flags in your face, but subtletly imparts the Zionist message that Jews belong in Israel.