I watched Papillon, Michael Noer’s usually gripping 2017 film, on Netflix the other night. It’s based on an international bestseller published in the late 1960s. The author, a petty thief from Paris named Henri Charriere, was wrongfully convicted of murder in 1931. For the next 14 years, he languished in a remote and hellish prison in tropical French Guiana, which lies on the northeast coast of South America.

Charriere spent part of his exile on Devil’s Island, which, along with Royale and Saint Joseph, form the chain of Salvation Islands in the southern Atlantic Ocean.

Originally a leper’s colony, Devil’s Island received its first batch of prisoners in 1852, and closed in 1953. Seventy five thousand men were shipped there over the course of a century and only 5,000 survived long enough to serve out their sentences.

Upon their release, they were forced to live in French Guiana — an underdeveloped country of vast unspoiled forests, treacherous swamps and high mountain ranges — for up to a period of time equal to their incarceration.

Less than one square kilometre in size and rising 40 meters above sea level, Devil’s Island is little more than a rocky islet covered by brush and palm trees. From a distance, it looks idyllic, the possible venue of a fancy resort in the tropics.

It was anything but paradisiacal. Conditions were, in fact, brutal. Prisoners were treated like animals by the authorities. They subsisted on paltry meals. They were compelled to work long hours on useless projects in the relentless humid heat. They constantly had to fend off insects and snakes.

Acts of rebellion were immediately quashed. Disobedient convicts were beaten and consigned to dark isolation cells, which could break the strongest and most resilient of men.

Prisoners convicted of murdering fellow inmates or guards were summarily executed by guillotine. On the order of the warden, prisoners had to watch the gory spectacle.

The chances of escape were next to nil. The rough waters surrounding the island were shark-infested and the cross-currents were dangerous. Which is why well-behaved prisoners were allowed to leave their cells and wander around at will.

A handful, like Charriere, escaped. Pulling off this incredible feat required ingenuity, courage, immense physical strength and an ability to swim.

Apart from hardened and incorrigible criminals, Devil’s Island held a considerable number of political prisoners.

The most famous one, Alfred Dreyfus, was a French Jewish army officer falsely accused of treason and sentenced to life imprisonment there.

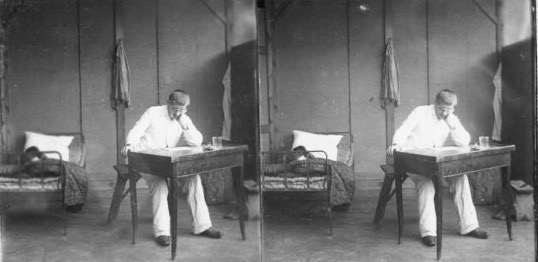

Charged with spying for Germany, he spent 1,517 days on the island from April 13, 1895 to June 9, 1899. Dreyfus was assigned to a hut near the ocean and lived in solitary confinement. He was not permitted to converse with a guard stationed nearby. At night, he was shackled to his bed.

He read a lot, kept a journal, and wrote some 1,000 letters to his wife in France. Cut off from the news of the day, he did not know that his case had spiralled into a cause celebre that split the nation into two irreconcilable camps.

Dreyfus’ supporters won his release from the dreaded island, but seven years would elapse before he was finally exonerated and restored to his rank.

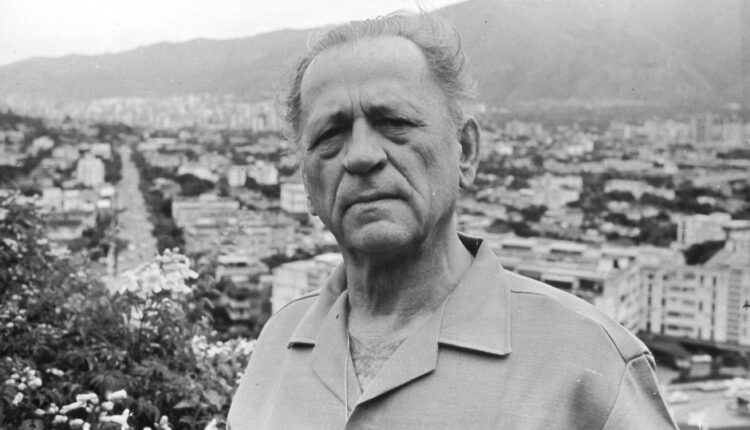

As for Charriere, he lived out his life quietly in Venezuela. His memoir made him wealthy, but questions about its authenticity arose after its publication.

The penal colony on Devil’s Island has fallen into disrepair since its closure 65 years ago and appears to be off-limits to visitors. The adjoining islands, Royale and Saint Joseph, are open to tourists.

It is probably hard to believe today that these islands were once the gateway to hell.