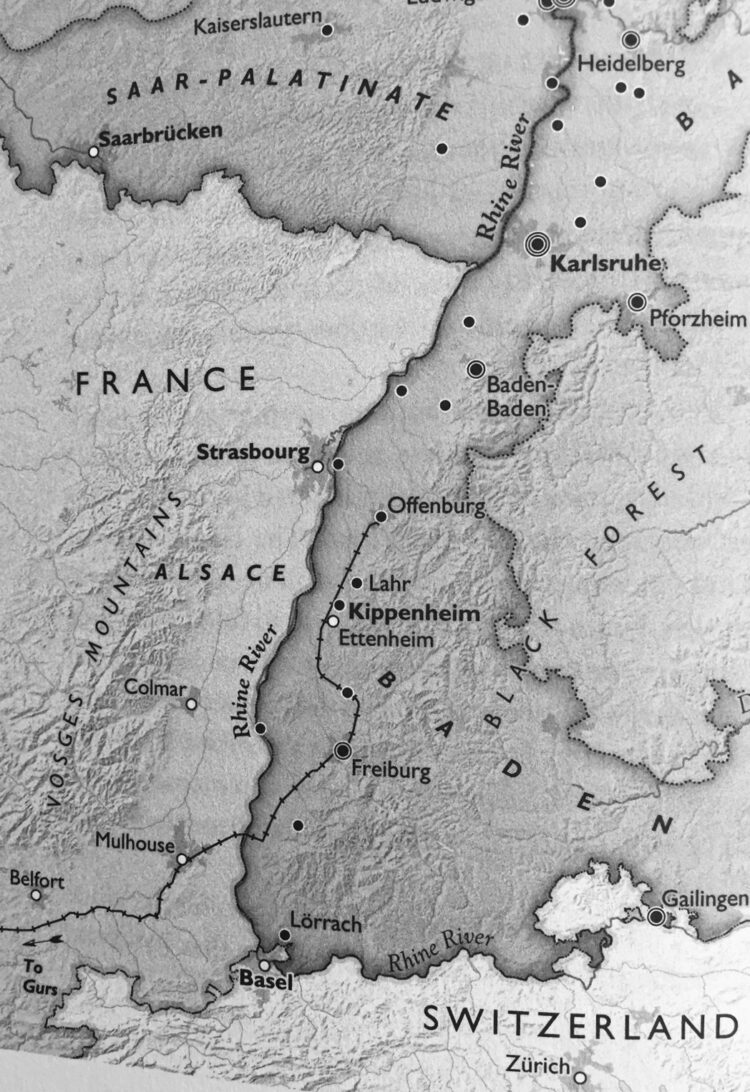

Kippenheim, a village in Germany’s southwestern Baden region, is nestled in the foothills of the picturesque Black Forest. On the eve of World II, Kippenheim’s population was 1,800. Fifty eight percent of its residents were Catholics and 33 percent were Protestant Lutherans. Only 144 of its inhabitants were Jewish.

Jews arrived in Kippenheim in the 17th century and gradually prospered. In 1808, the grand duke of Baden became the first German ruler to offer his Jewish subjects the promise of civil and religious equality if they conformed to German cultural and educational practices. It was an offer the majority of Jews heartily embraced.

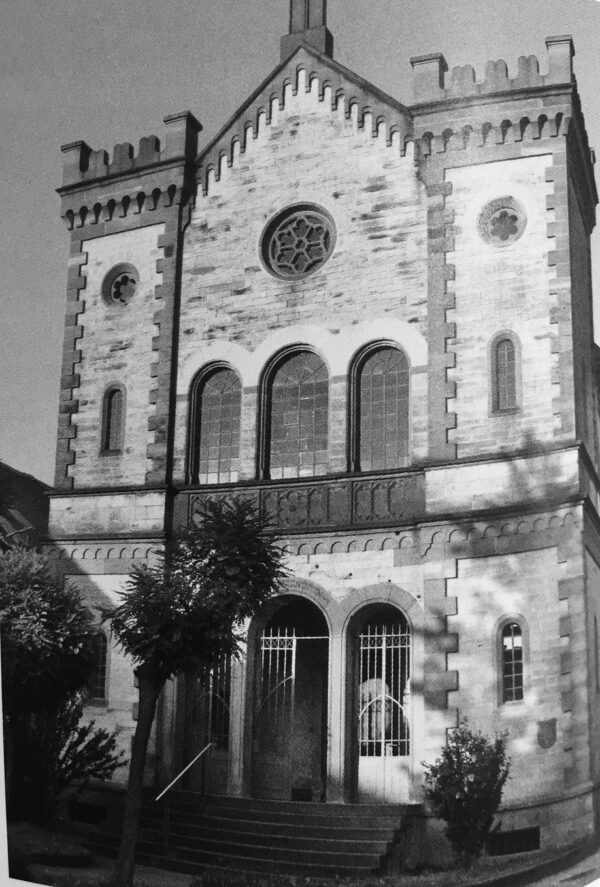

At the end of the 19th century, 323 Jews lived in Kippenheim. By then, they had established successful businesses and built a Moorish-style sandstone synagogue in the center of the village. During this period, Jews from Kippenheim began migrating to the nearby cities of Mannheim and Karlsruhe.

When World War I broke out, Jewish men volunteered to serve in the armed forces. Eight Jewish soldiers were killed in the course of the hostilities. A memorial honoring their sacrifice was erected in a Jewish cemetery in the adjacent village of Schmieheim.

Jews and Christians in Kippenheim coexisted, although Christian farmers viewed Jewish cattle dealers with suspicion.

Only three Kippenheimers cast their ballots for Adolf Hitler’s Nazi Party in the 1928 general election, but four years later the Nazis increased their share of the vote to 36 percent. Hitler’s appointment as chancellor in 1933 sealed the fate of Kippenheim’s Jewish community.

The tempo of Nazi persecution of Jews picked up throughout the 1930s. The synagogue was vandalized and converted into an agricultural warehouse. Jews were forced to sell their companies to Christians for nominal sums. In 1935, local Nazis passed a resolution denouncing Jewish settlement in Kippenheim and Christian-Jewish fraternization.

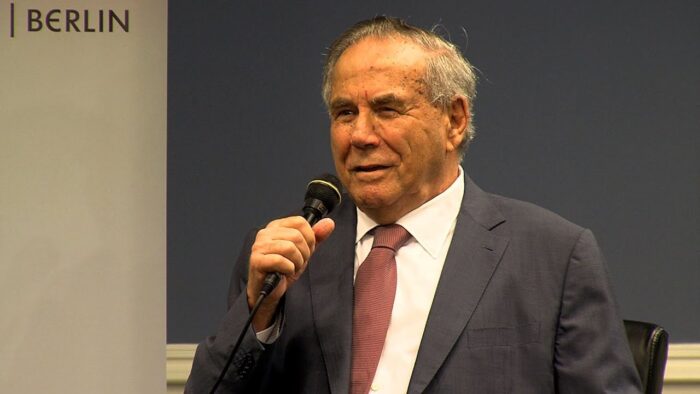

There was no longer a place for Jews in the village. Yet “many Christians maintained good relations with their Jewish neighbors in private, while keeping their distance in public,” says Michael Dobbs in The Unwanted: America, Auschwitz, And A Village Caught In Between (Alfred A. Knopf).

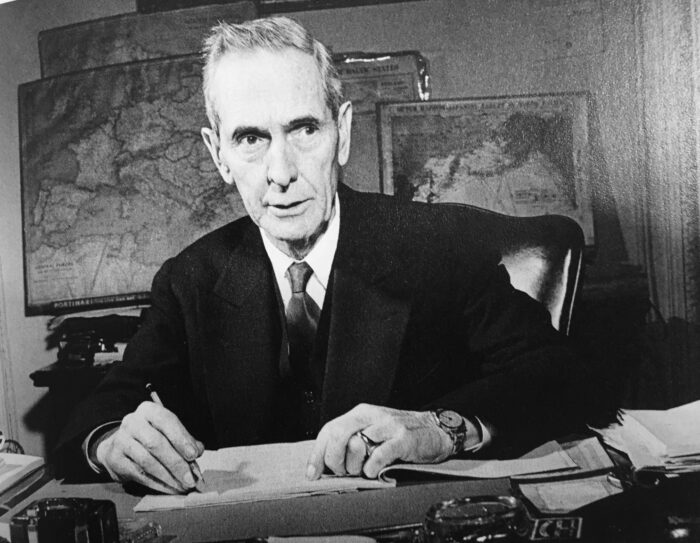

Drawing on previously unpublished diaries, letters, visa records and interviews, Dobbs has written a book that comprehensively explains what happened to the Jews of Kippenheim after Hitler’s accession to power.

Some managed to escape abroad thanks to U.S. visas. Others were rounded up and sent to a holding camp in Vichy France, an ally of Nazi Germany. Still others were transported to the Auschwitz-Birkenau extermination camp in Poland.

Dobbs, a former reporter for The Washington Post now on the staff of the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, D.C., weaves all these elements together seamlessly in an account that lays bare the cruelty and indifference that enveloped German Jews from 1933 onward.

Jews in Kippenheim felt the effects of Nazi antisemitism keenly. On Kristallnacht, on November 10, 1938, several truckloads of Hitler Youth from the town of Lahr descended on the synagogue and wrecked its interior. They wanted to set fire to the building, but Christian neighbors objected, protesting that adjoining “German property” might be burned. To add insult to injury, the elected leader of the Jewish community, Hermann Wertheimer, was held responsible for repairing the damage to the shul.

Long before this catastrophic event, Jews from Kippenheim, having read the writing on the wall, applied for U.S. visas at the American consulate in Stuttgart. The consul general, Samuel Honaker, was sympathetic to the plight of Jews. By mid-1938, the consulate was approving more than 1,500 visas a month, 90 percent of them to Jews. But the overall refusal rate exceeded 60 percent. Of the 23,000 people who had applied for visas in the past year, some 14,000 were denied a formal appointment.

U.S. immigration laws had been rigorously tightened in 1924 to favor Europeans of Nordic and Anglo-Saxon stock. U.S. President Franklin Roosevelt empathized with the victims of Nazi oppression, but in deference to homegrown xenophobia and antisemitism, he made no effort to liberalize immigration practices. However, he supported filling the German and Austrian immigration quota, thereby enabling these Jews to settle in the United States.

American officials who opposed the admission of German Jews often cited the hazard of spies infiltrating into America in the guise of refugees. Breckinridge Long, the assistant secretary of state, believed that the Gestapo was manipulating the refugee flow for espionage purposes. J. Edgar Hoover, the director of the Federal Bureau of Investigation, complained that “Germans desiring to enter the United States for subversive purposes” had little difficulty acquiring quota visas.

In fact, as Dobbs points out, there is no evidence that Nazi agents and fifth columnists managed to get into the United States disguised as Jewish refugees.

Despite widespread American opposition to Jewish migrants, tens of thousands were allowed in between 1933 and 1945, says Dobbs. The figure he cites is 204,085.

“Although the United States could clearly have done more to help victims of Nazi persecution, the number of those admitted was scarcely negligible. The only territory that accepted more Jews than the United States … was British-administered Palestine,” he writes.

German Jews whose visa applications had been rejected or who could not leave Germany found themselves increasingly isolated and in great danger.

In 1940, Baden and Saar-Palatinate were the first states in the Third Reich to expel Jews and become Judenfrei, or “Jew-free.” Upwards of 6,500 Jews from these areas were rounded up in an operation commanded by Adolf Eichmann. They were dispatched to Gurs, an internment camp in Vichy France in the shadow of the Pyrenees mountains that had been built to house the defeated soldiers of the Spanish civil war.

Vichy officials demanded their departure from France, and Roosevelt agreed to admit Baden deportees on a case-by-case basis. The head of the U.S. consulate in Marseille, Hiram Bingham Jr., the son of an explorer who had rediscovered the forgotten Inca city of Machu Pichu in Peru, was sympathetic to their cause. By Dobbs’ estimate, 12,000 predominantly German refugees registered for visas at the consulate.

Another American, Varian Fry, the Marseille representative of the New York-based Emergency Rescue Committee, attempted to help the refugees as well.

Prior to February 1941, the principal escape route from unoccupied France was over the Pyrenees and then through Spain to Portugal. A second route extended from Marseille to the French West Indies island of Martinique. From there, a refugee could reach New York and other U.S. ports. But by the summer of 1942, mass escape was no longer feasible, Dobbs notes.

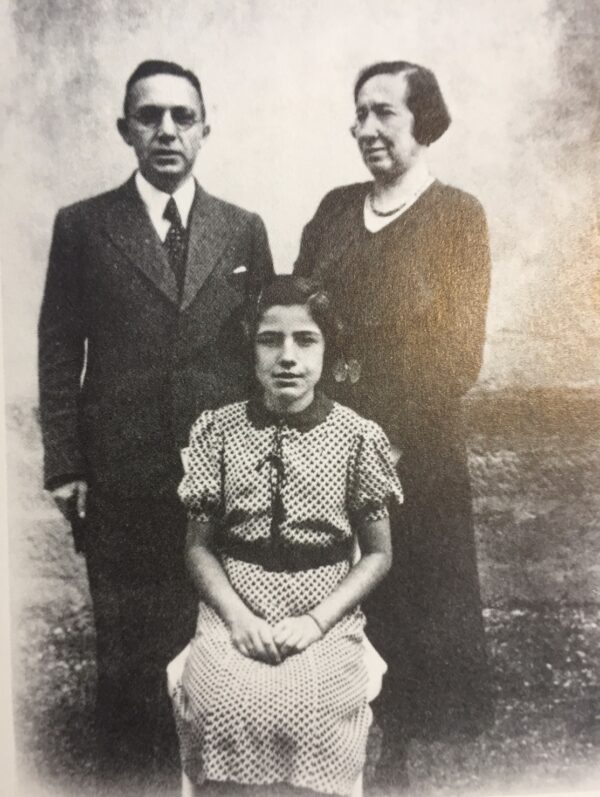

By his estimation, 25 percent of the internees in Gurs and other French camps died, many from malnutrition and typhus. Four out of ten were deported to Auschwitz, including Max and Fanny Valfer of Kippenheim, both of whom had applied for a U.S. visa. Eleven percent fled abroad, primarily to the United States. A further 12 percent, mainly children and elderly women, found hiding places in France.

Thirty one Jews from Kippenheim died as a result of Nazi persecution, a death rate of just over 21 percent, according to Dobbs. By comparison, one-third of German Jews perished during the Holocaust.

“Wealth, education and family ties in the United States all contributed to the ability of Jews to organize their escape,” he says.

After Germany’s defeat, French forces occupied Kippenheim, and all visible traces of the Nazi era were removed. Starting in 1948, a series of trials of local Nazis took place. The Nazi Party leader in the district, Richard Burk, was cleared of “crimes against humanity.” He blamed subordinates who had long since died or disappeared.

The new West German government permitted Holocaust survivors to file legal claims for property either confiscated by the Nazis or sold under duress at absurdly low prices.

The long-abandoned synagogue was restored on the initiative of Israeli industrialist Stef Wertheimer, who left Kippenheim with his family in 1937.

Inspired by the stories of survivors, the mayor of Kippenheim, Willi Mathis, commissioned a two-volume memorial book listing the names of every person buried in the Jewish cemetery. More books on the history of the Jewish community followed. The homes of many of the deported and murdered Jews were commemorated with cobblestone-size tablets known as stumbling stones.

These were fine gestures by decent, well-meaning Germans, but the Nazis had achieved their overarching objective of rendering Kippenheim Judenfrei.