David Fincher’s workmanlike film, Mank, shines a spotlight on one of the most productive collaborative partnerships in the annals of the Hollywood movie industry.

Citizen Kane, the enduring 1941 cinematic classic, was the brainchild of Herman Mankiewicz, a seasoned wordsmith who struggled with alcoholism, and Orson Welles, a precocious upstart who basked in self-adulation.

Now streaming on Netflix, Mank is both a detached pen portrait of Mankiewicz, a celebrated scriptwriter who shared the 1942 Academy Award for best original screenplay with Welles, and a scathing portrayal of old Hollywood. Two hours and 12 minutes in length, Mank is longer than most mainstream movies, but it moves along at a satisfying pace and hardly seems padded.

Its departure point is 1940. Mankiewicz (Gary Oldman), confined to bed, is recovering from a fairly serious car accident. He’s being treated by an efficient German nurse whom he refers to as fraulein. As he leans against the headboard, he begins writing in longhand.

Citizen Kane is to be directed by Welles, a 24-year-old wunderkind who’s the talk of the town. Having made his mark on radio and the stage, Welles is intent on leaving an indelible imprint in Hollywood.

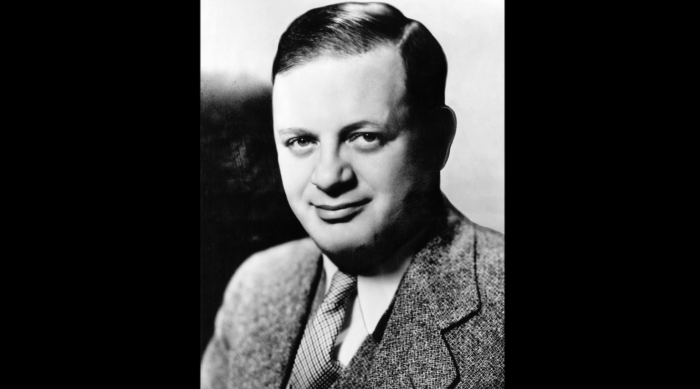

Mankiewicz, a Jew, is equally famous. A former journalist who cut his teeth as a drama critic in New York City, he arrived in Los Angeles in the 1920s and never looked back. Such was his success that, in 1926, he sent this self-congratulatory telegram to hotshot Chicago reporter Ben Hecht: “Millions are to be grabbed out here, and your only competition is idiots.”

By 1940, Mankiewicz was at the top of his form, a rumpled, immensely talented writer and witty raconteur whose personal deficiencies — a thirst for alcoholic beverages and a lust for gambling — threatened to derail his illustrious career. At one juncture, his long-suffering wife, Sara (Tuppence Middleton), refers dispiritedly to his “suicidal drinking.”

Oldman delivers a keen yet understated performance that holds this atmospheric film together.

Mankiewicz had no illusions about his status in Hollywood, as a sharply-observed scene in Mank illustrates. When Louis B. Mayer (Arliss Howard), the movie mogul, asks Irving Thalberg (Ferdinand Kingsley), the protean producer, to identify a person he has just briefly met at a party, Thalberg laconically replies, “Just a writer.”

Mayer, though somewhat crude, comports himself as a savvy operator. As he aptly observes, “This is a business where the buyer gets nothing for his money but a memory.”

Mankiewicz’s latest project teeters on the controversial. It’s about Charles Foster Kane, a powerful newspaper publisher who bears a startling resemblance to William Randolph Hearst (Charles Dance), whose chain of newspapers and magazines are read by the masses. Mankiewicz is friendly with Hearst and his blonde mistress, Marion Davies (Amanda Seyfried), an aspiring actress who’s more intelligent than she appears.

Mankiewicz has acquired inside knowledge of the pair by having attended lavish, candle-lit dinners at Hearst’s palatial estate, San Simeon. These soirées are attended by, among others, Mayer, who considers Hearst a valued friend. At one of these gatherings, Mankiewicz goes off on a drunken tangent, prompting Mayer to denounce him as a court jester.

Welles sets a tight deadline of 60 days for Mankiewicz to finish his portion of the screenplay. He finishes on time, and Welles is pleased. Welles’ brief conversations with Mankiewicz are usually over the phone rather than in person.

A dark cloud descends when Mankiewicz’s younger brother, Bob, an up-and-coming director, advises him to disengage from Citizen Kane, warning he may be courting problems with Hearst. Later, having read the script, Bob exults, “It’s the best thing you’ve ever written.”

Mank swings back and forth between the 1930 and 1940s and unfolds against the backdrop of the misery of the Depression. There are several references to the acclaimed novelist Upton Sinclair, who ran unsuccessfully for California’s governorship in 1934. Sinclair, a democratic socialist, is defeated by a Republican supported by Hollywood’s power elite. Mayer disparages him as “a lousy Bolshevik.” Mankiewicz, a leftist of sorts, keeps his views to himself.

Mank is shot in silvery black and white shades in an unmistakable retro style that harkens back to the film noir era. It resurrects, in fits and starts, a creative partnership that has yet to be matched.