After signing historic normalization agreements with the United Arab Emirates, Bahrain and Sudan this past summer, Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu may have assumed that Saudi Arabia would be next in line to establish diplomatic relations with Israel.

U.S. President Donald Trump, who was instrumental in facilitating these path-breaking accords, buoyed Netanyahu’s confidence by boldly predicting that Saudi Arabia and four unnamed Arab countries were on the cusp of recognizing Israel.

Trump’s upbeat comment may well have reinforced Netanyahu’s belief that he could entice still more Arab nations, notably Saudi Arabia, to sign peace accords with Israel without resolving the festering Palestinian problem.

Their calculations turned on the assumption that the Palestinian issue is not as relevant as it previously was and that Israel and Saudi Arabia share a common strategic interest in containing Iran, the preeminent Shi’a power in the Middle East.

They were also encouraged by the attitude of the Saudi heir to the throne, Prince Mohammed bin Salman. In 2018, he told American Jewish community leaders that Israelis were entitled to live in their ancestral homeland.

It is now increasingly clear that Trump and Netanyahu were laboring under a grand delusion. Saudi Arabia, at least for the foreseeable future, has no intention of recognizing Israel, leaving Netanyahu quite disappointed and perhaps even frustrated.

Saudi Arabia’s reluctance to forge a rapprochement with Israel is quite evident, judging by a barrage of recent statements from influential Saudis.

On December, 6, a key member of the Saudi royal family launched a stinging diatribe against Israel. Last month, the Saudi foreign minister categorically denied that Netanyahu had met the crown prince in Saudi Arabia. And in October, another Saudi notable described Israel as an “unjust” cause.

Taken together, these remarks strongly suggest that Saudi Arabia — the seat of Islam and the repository of vast oil reserves — is far from ready to make peace with Israel.

Saudi Arabia, however, quietly supported Israel’s peace accords with two of its closest regional allies, the United Arab Emirates and Bahrain. And the Saudis did not object to Israel normalizing bilateral relations with Sudan.

And in the spirit of the Abraham agreements, Saudi Arabia permitted Israeli aircraft to use its air space en route to other destinations.

Beyond these concessions, Saudi Arabia has not budged from its firmly-held belief that Israel’s conflict with the Palestinians must be resolved before it can seriously consider establishing formal ties with Israel.

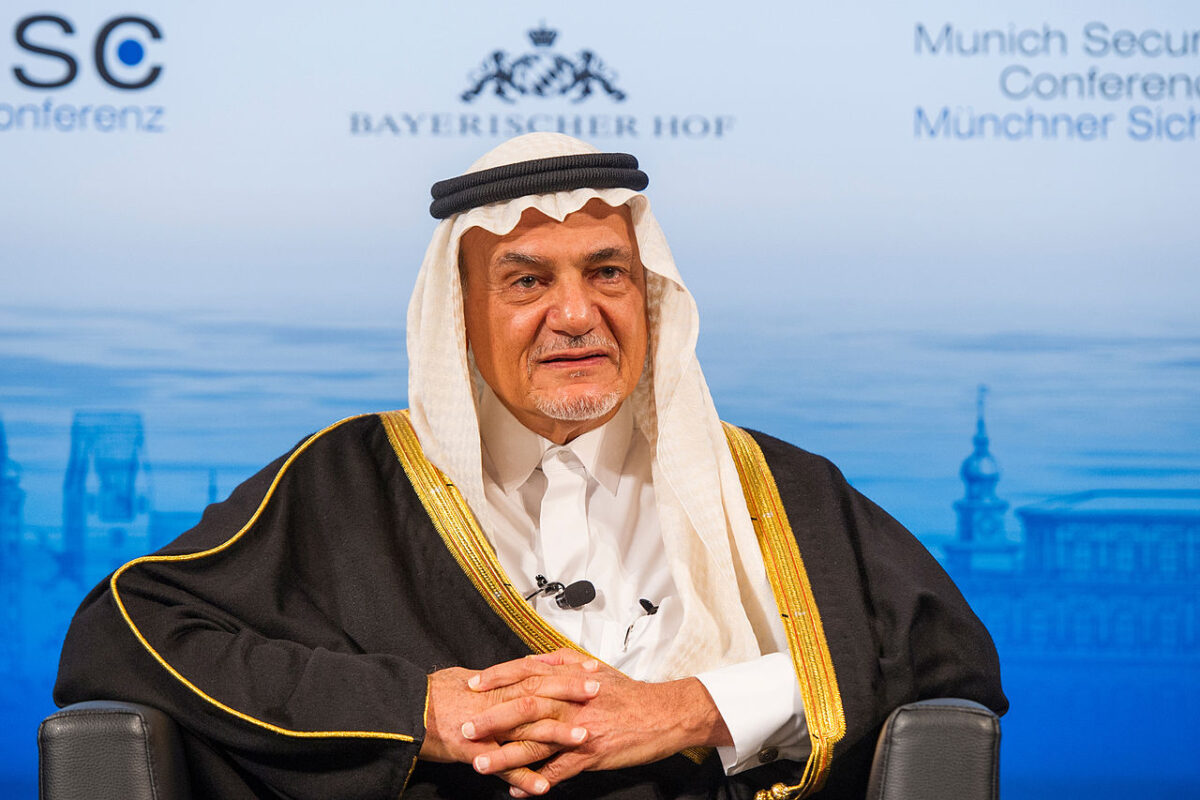

This is the policy to which King Salman, the crown prince’s father, adheres unwaveringly. It is also the position of Prince Turki al-Faisal al-Saud, the former Saudi ambassador to the United States and Britain and the ex-director of Saudi Arabia’s intelligence service.

At a panel discussion in Bahrain, he bitterly denounced Israel. Claiming he was speaking in a private capacity, he said that Israel has arrested thousands of Palestinians and placed them in “concentration camps under the flimsiest of security accusations.” He added that Israel demolishes Palestinian homes, assassinates “whomever they want to,” and denies Israeli Arabs equal rights. He compared Israel’s security barrier along and inside the West Bank to an “apartheid wall.”

Al-Saud’s blistering remarks were rejected by Israeli Foreign Minister Gabi Ashkenazi as “false accusations” which do not reflect the “changes the region is undergoing.”

Certainly, Al-Saud’s verbal onslaught was at odds with his apparent openness to Israel.

Six years ago, he appeared on a panel with Amos Yadlin, a former head of Israeli military intelligence. In the following two years, he met Yair Lapid, the leader of the centrist Yesh Atid Party, shook hands with the then-defence minister, Moshe Ya’alon, and shared a stage with Yaakov Amidror, Netanyahu’s former national security adviser. Three years ago, he agreed to appear on a panel with Efraim Halevy, a former director of the Mossad.

Al-Saud, though, did not pour cold water on the idea that a Saudi peace agreement with Israel is possible.

Urging Israel to accept the 2002 Arab League proposal, which was crafted in part by Saudi Arabia, he called for a two-state solution, with East Jerusalem serving as the capital of a Palestinian state. He also said that a “fair solution” of the Palestinian refuge problem is necessary.

In conclusion, Al-Saud said that Saudi Arabia and Israel can jointly confront their common enemy, Iran, once a resolution of the Palestinian issue has been achieved.

Saudi Arabia’s cool and cautious approach to Israel was on display again after Israeli newspapers reported that Netanyahu and Yossi Cohen, the head of the Mossad, had conferred with the crown prince in the Red Sea coast city of Neom on November 22.

Unrestrained by diplomatic niceties, Israeli Education Minister Yoav Gallant confirmed that the meeting had taken place. “This is something our ancestors dreamed about,” he gushed.

But tellingly enough, Netanyahu and the crown prince remained conspicuously silent.

Saudi Foreign Minister Prince Faisal bin Farhan swiftly denied that Netanyahu and Cohen had paid a visit, insisting the crown prince had met only U.S. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo.

In all probability, Farhan was less than truthful. Netanyahu and Cohen most likely met the crown prince. But judging by Farhan’s reaction, the Saudis would have preferred to keep the meeting under a cloak of secrecy.

It’s very possible that the crown prince deliberately kept his father out of the loop, assuming he would disapprove of it.

In any event, the crown prince must tread carefully. There are factions in the ruling House of Saud, all aligned with King Salman, that oppose peace with Israel unless it comes to terms with the Palestinians. As well, Israel is very unpopular in Saudi Arabia. The reason is clear. Many Saudis have been weaned on decades of anti-Israel and antisemitic propaganda and cannot shake it off.

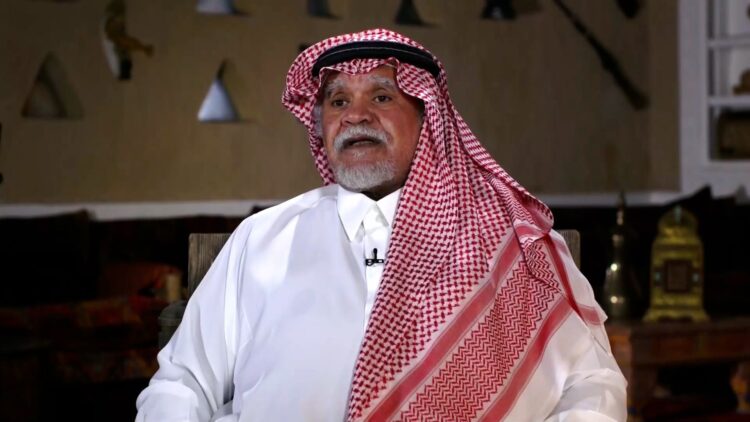

Prince Bandar bin Sultan bin Abdulaziz, the Saudi ambassador to the United States from 1983 to 2005, expressed this animosity during a broadcast in October on the Saudi-controlled Al Arabiya satellite channel.

After denouncing the Palestinian leadership as ineffectual, particularly during the stewardship of the late Yasser Arafat, he said, “The Palestinian cause is a just cause, but its advocates are failures. The Israeli cause is unjust, but its advocates have proven to be successful.”

Abdulaziz’s observation, though harshly critical of the Palestinians, was symptomatic of the visceral animus that governs Saudi attitudes toward Israel.