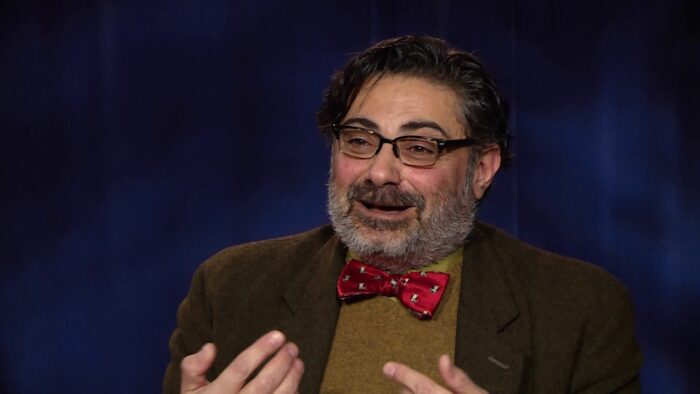

Franck Salameh describes his bitter-sweet book, Lebanon’s Jewish Community: Fragments of Lives Arrested (Palgrave Macmillan), as a “memorial” and “act of remembrance” to commemorate what was arguably the oldest and most indigenous community in Lebanon.

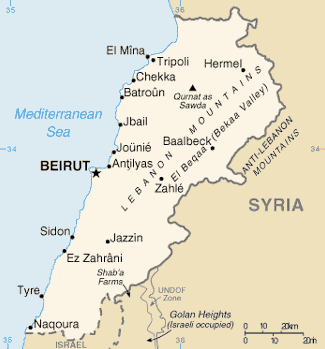

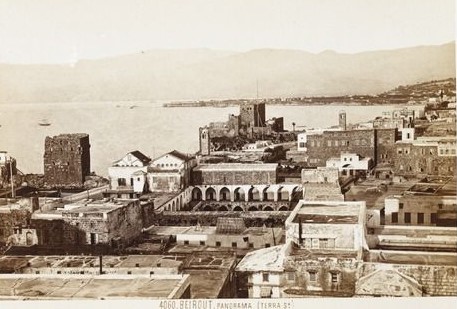

Fourteen thousand strong at its height in the 1940s, it was the smallest of Lebanon’s 20 legally recognized ethnic-religious groups, its origins to be found in classical antiquity and biblical times. Consisting of merchants, shopkeepers, artisans and professionals, it grew and flourished following Israel’s birth in 1948, in sharp contrast to besieged neighboring Jewish communities in the Arab world.

Unlike Syrian, Iraqi or Egyptian Jews, Lebanese Jews were never dhimmis, not having been subjected to “the legal restrictions imposed by traditional Islam.” No did they experience “the degrading treatment or discriminatory policies inflicted on minorities” elsewhere in the Middle East, Salameh notes.

Jewish families like the Safras and the Zilkhas helped turn Lebanon into a regional financial and banking hub. Guy Beart, the father of French actress Emmanuelle Beart, was a renowned musician and songwriter. Toufic Mizrahi, a journalist, was the founding editor of Le Commerce du Levant, the preeminent French-language economic magazine in the Middle East.

But after the 1948 Arab-Israeli war, informal “limitations” were placed on Jews, who were blocked from reaching higher echelons in government and the civil service and were denied jobs in the diplomatic corps. Jews employed by the police, army and security services were viewed with “circumspection,” and restrictions were placed on the authority they wielded and the promotions to which they could aspire.

From the moment Lebanon was established as a state in 1920, Lebanese Jews committed themselves to maintaining it as an independent, sovereign and multicultural haven of minorities rather than as an Arab republic.

Given the pressures of the Arab-Israeli conflict and the intercommunal violence that pitted Christians against Muslims in civil wars in 1958 and 1975, Lebanese Jews emigrated in incremental waves, resettling in France, Canada, Latin America, Israel and the United States.

With these dispersals, this ancient community has all but vanished. According to one estimate, less than 30 Jews live in the entire country today. “Most of those Lebanese Jews … are at best ‘museum curiosities,’ living in dissimulation and seclusion, often marrying into Christian families, and slowly committing their Jewish heritage and identity and contributions to oblivion,” writes Salameh.

Although Jews played an important, though discreet, role in the formation of Lebanon in the first half of the 20th century, they have, more or less, been ignored by Lebanese scholars. The literature that has recognized their presence, if only in passing, has been “scant, fragmentary and restricted in scope,” he says more in sadness than indignation.

“Lebanese Jewry has indeed all but disappeared from Lebanon’s political, cultural and social landscapes of the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries, in spite of Lebanon having been a homeland for Jews upwards of 2,000 years,” he says.

He attributes this to several factors: the rise of Arab nationalism in Lebanon during the 1940s and 1950s, the birth of Israel, the residency of Palestinian leader Haj Amin al-Husseini in Lebanon after his expulsion from Palestine, and the resurgence of antisemitism in the region after Israel’s establishment.

The topic, however, has interested foreigners. Salameh — a professor of Near Eastern Studies at Boston College — mentions two works: Kirsten Schulze’s The Jews of Lebanon, which, though excellent in his opinion, requires updating, and Tomer Levi’s The Jews of Beirut, which only deals with the late Ottoman and early French mandate periods.

Salameh is not a specialist on Lebanese Jews, his area of expertise being Middle Eastern intellectual history and twentieth century nationalism in Lebanon. Nonetheless, he has produced a solid and empathetic work of scholarship, a thoroughly-researched, amply documented and keenly-observed volume supplemented by the testimonies of Lebanese Jews living abroad.

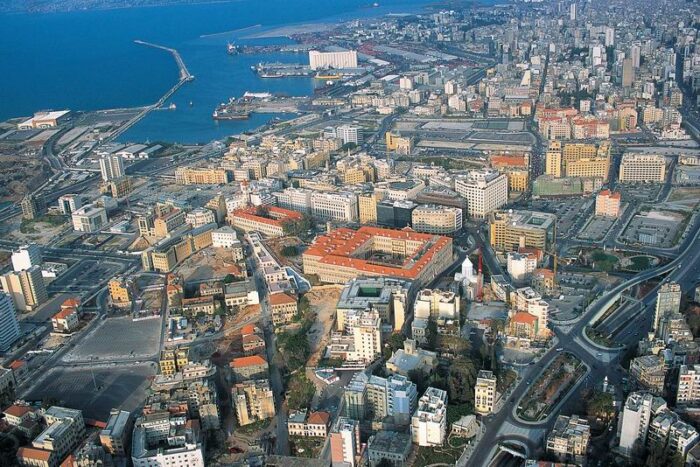

He is a Christian who grew up in East Beirut, a predominately Maronite neighborhood inhabited also by Jews, Armenians and French, British and American expatriates. As he fondly looks back at his childhood, he recalls the enchanting views of the Mediterranean Sea from his sunny terrace and the fragrances of salt-sprayed breezes and citrus orchards.

It’s a tantalizing picture of a nation that, until about the 1960s, was known as the Switzerland of the Middle East. The Lebanon that captured his heart and mind was at once liberal, unorthodox, irreverent, libertine, iconoclastic and open to its religious and ethnic diversity. It was a vibrant commercial, cultural and intellectual entrepôt which tried to stay clear of the Arab-Israeli dispute.

In his harsh estimation, Lebanon has since been transformed into “a lawless gateway for motley rejectionists, international criminals, petty revolutionaries and armed bands waging Arab proxy wars against each other and Israel, from and on Lebanese territory.”

Lebanese Jews flourished when Lebanon was a multicultural nation dominated by the Maronites, committed to a Mediterranean federation of minorities, and unencumbered by the politics of Arab identity and the resentments of the Arab-Israeli conflict.

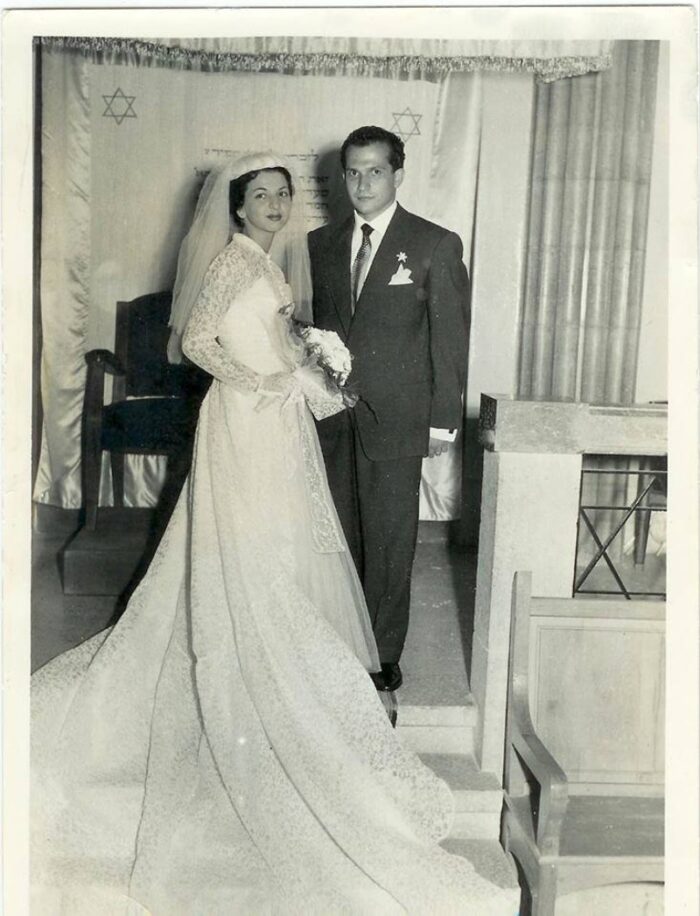

During the Jewish community’s heyday, as one Lebanese Jew recalls, “the life of Jews in Lebanon was indeed a privileged one within the challenging context of the Jews in Arab lands.” Salameh quotes another Lebanese Jew as saying, “In times of peace, we never suffered any form of discrimination … Our lives were very similar to the lives of other Lebanese from other communities.”

Salameh believes that Jews and Maronites were joined at the hip by a cultural and historical “romance” of sorts. Jews often remained aloof from Lebanon’s sectarian politics and tried to maintain a low political profile. But they “leaned more sympathetically” toward the Christian community, and many well-to-do Jewish families enrolled their children in Christian and Maronite schools, even if most Jewish students attended Alliance Israelite Universelle schools. In addition, some Jewish surnames, ranging from Hassoun and Atties to Srours and Malehs, were practically indistinguishable from Christian names.

The Maronite patriarch from 1932 to 1955, Antony Peter Arida, took a special interest in the well-being of Lebanese Jews, while the archbishop of Beirut in the 1940s, Ignatius Mobarak, endorsed the return of Jews to Palestine and praised their achievements there. One of the presidents of Mandatory Lebanon, Emile Edde, advocated an alliance with the Jews of Palestine.

After the outbreak of the first Arab-Israeli war, Maronite militiamen protected Jewish neighborhoods from Arab reprisals. “This would remain the case through the 1950s and 1970s, when Arab nationalist and anti-Jewish demonstrations became a staple of Muslim Lebanese political life,” says Salameh.

“It was in the main Maronite Lebanese nationalism, and its vocal rejection of Lebanon’s putative Arab identity, that drew the Maronites and Jews closer to each other” he writes. “Maronites believed in a Western-oriented, politically sovereign and militarily strong and self-reliant Lebanon, dominated by a Christian worldview, and separate from the rigid nationalist models emanating from the Arab Muslims of the neighborhood. But the Maronites were divided among themselves over the future of Lebanon. Some factions believed in total divorce from the Arab world. Others pushed for an entente cordiale with Lebanon’s Muslims and advocated a power-sharing agreement that would recognize Lebanon’s … changing demographics and an imminent ‘triumph’ of an Arabist narrative …”

In the end, he observes, the Maronite leadership sold its soul to “the phobias of the neighborhood’s Muslims.” Some Maronites, influenced by Hezbollah, have bought into antisemitic tropes and canards about international Jewish conspiracies.

Salameh argues that Lebanon’s transformation into a full-fledged Arab state occurred after one of its post-independence Maronite presidents, Bechara El-Khoury, agreed to share power with Muslims under the 1943 National Pact. The flight of some 300,000 Palestinians into Lebanon after the 1948 Arab-Israeli war had an impact as well on Lebanon’s demographic profile and its status as a confederation of minorities.

“This also meant that Lebanon’s Jews would now be offered as sacrificial lamb, to be burned on the altar of Arabism in atonement for the losses visited by an ‘arrogant’ upstart “Jewish entity” — a ‘foreign body,’ as it were, germinating where an ‘Arab state’ should have taken shape,” he says.

“By that time, the Christians had lost their hold on Lebanon and the direction of Lebanese politics,” he adds. “Gone was Lebanon’s commitment to neutrality in the Arab-Israeli conflict.”

Lebanese Jews, though generally supportive of Jewish statehood in Palestine, maintained a distance from the Zionist movement and few bothered immigrating to Israel. “The rationale for this approach might have been to avoid endangering the Lebanese Jewish community’s standing with the Lebanese Muslims,” he explains.

Nevertheless, some Lebanese politicians accused Jews of dual loyalty. Emile Boustany, a Druze member of the Socialist Party, demanded that strict measures be taken against the country’s Jews, claiming they were “natural allies” of Israel. The Phalange, a Maronite political party, came to the defence of Jews.

But, as Salameh suggests, Lebanon was split over the question of Lebanese Jews, with the great majority of Arab nationalists siding with Boustany and Lebanese nationalists, including Muslims, coming out in support of Jews.

Even before the 1967 Six Day War, Lebanese Jews felt threatened to some degree. In 1958, two bombs were defused in Wadi Boujmil, Beirut’s small Jewish quarter. During the war itself, when Jews experienced what Salameh calls “heightened instances of harassment,” the Lebanese government installed a permanent police station in Wadi Boujmil, while the Phalange provided security.

By then, two-thirds of Lebanese Jews had already emigrated, leaving 6,000 in the country. The second civil war effectively destroyed the remnants of the Jewish community.

During the 1970s, as the Palestine Liberation Organization formed a state-within-a-state in Lebanon, “acts of violence and vandalism” targeting the Jewish community became “a near daily occurrence.”

Salameh cites examples. In January 1970, an Arab nationalist gang detonated a bomb near the outer wall of a Jewish school in Beirut, causing considerable damage to the building. Yasser Arafat, the chairman of the PLO, condemned the attack, while the minister of interior, Kamal Jumblatt, denounced the perpetrators.

“The Lebanese government went to great lengths to guarantee the safety and security of the Jewish quarters, Jewish homes and Jewish businesses,” says a Lebanese Jew.

Despite these precautions, Lebanese Jews could never be sure what lay around the corner. In 1971, the secretary-general of the Jewish Communal Council, Albert Elia, was kidnapped, never to be seen again. Fourteen years later, with the civil war still raging, four leading members of the community — Elie Hallak, Chaim Cohen, Isaac Sasson and lie Srour — disappeared as well.

Lebanon today is virtually bereft of Jews, and Salameh compares the remaining ones to highly assimilated crypto-Jews who care very little about their Jewish identity. He mentions two such Jews: the historian Carol Hakim, the author of The Origins of the Lebanese National Idea and a convert to Islam, and the economist Ishac Diwan, who hails from one of the oldest Jewish families in Lebanon.

In any event, as he points out in his concluding chapter, Jews “seem to have been written out of Lebanese history.” Books dealing with Lebanese Jewish memory hardly exist, even though there is a sizeable Lebanese Jewish expatriate community that still yearns for the old country.

Salameh, in closing, leaves a reader in a melancholy state. “The Lebanese Jewish community has gone from being the most prosperous and secure of Near Eastern Jewish communities outside of Israel, to becoming a museum curiosity; a brittle specimen of a once proud community, today on the brink of oblivion.”