A seminal moment in Georgia’s history unfolded a few days ago.

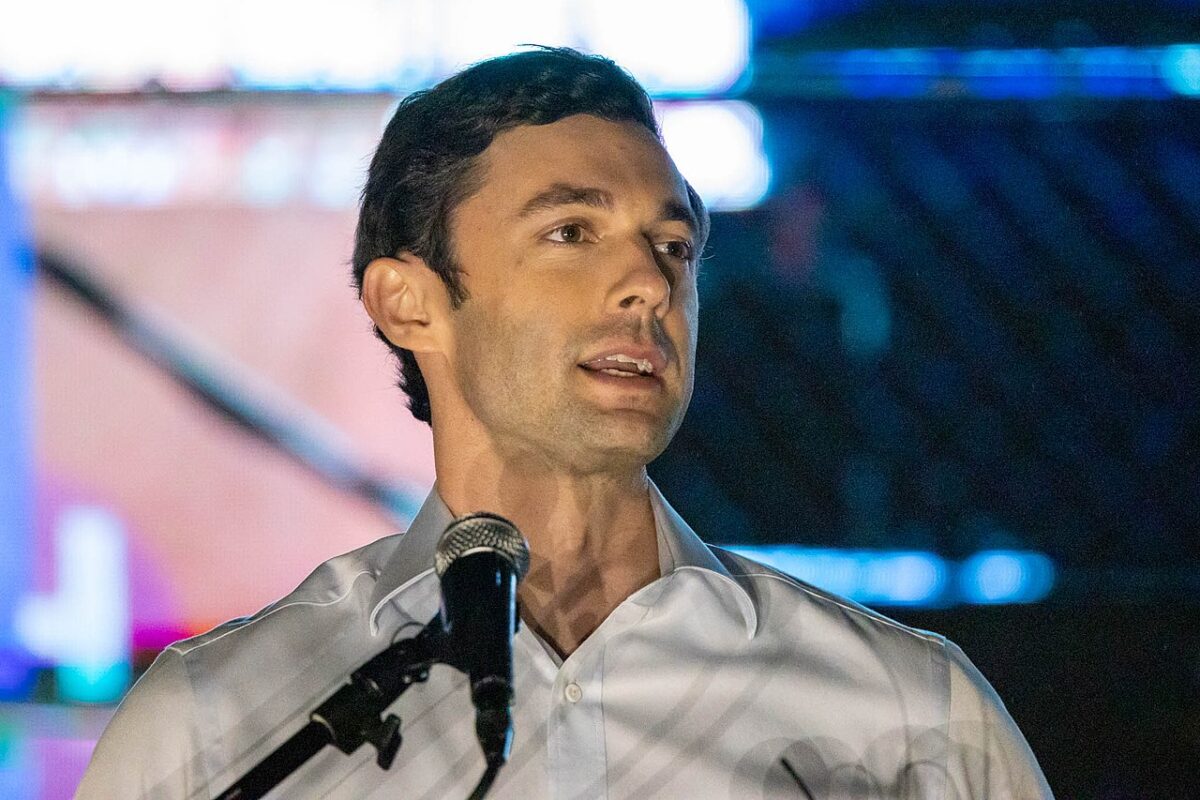

Jon Ossoff and Raphael Warnock were elected as the first Jewish and the first African-American senators to represent that southern state in the U.S. Senate.

(It could be argued that John S. Cohen, a journalist born in Augusta, was technically the first Jewish senator from Georgia. A Jew on his father’s side, he adopted his mother’s Episcopalian faith and considered himself a Christian. From April of 1932 to January of 1933, he served in the U.S. Senate, filling a vacancy caused by the death of his predecessor).

In the runoff election on January 5, Ossoff and Warnock narrowly defeated the Republican incumbents, David Perdue and Kelly Loeffler, giving the Democratic Party control of the Senate.

Their victories illustrate the degree to which Georgia has been transformed since the segregationist Jim Crow era, when, as second-class citizens, African-Americans in southern states were the victims of blatant discrimination.

With few exceptions, they were denied the right to vote, turned away from restaurants and bars, forbidden to use the same bathrooms, barred from white-collar jobs, kept out of some universities, and banned from buying homes in white neighborhoods.

African-Americans temporarily achieved a measure of racial justice after the Civil War and during the subsequent short-lived Reconstruction period, but these rights were gradually withdrawn as segregation took hold in the Old South.

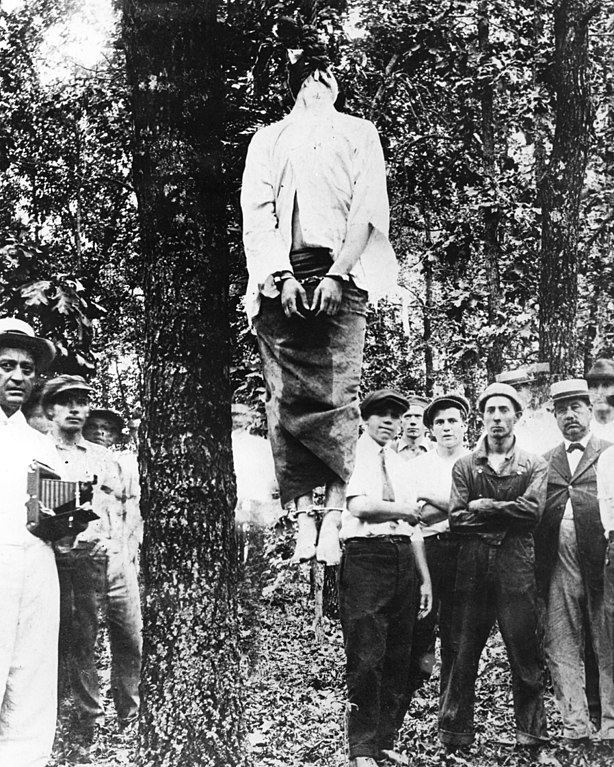

During this dark period, when the anti-black and antisemitic Ku Klux Klan was on the rise, African-Americans were terrorized and murdered if they failed to show due deference to local customs and laws. African-Americans who defied the status quo risked being strung up and lynched by vigilante mobs.

Southern Jews, being caucasians, did not face such existential threats and gained acceptance in the white community.

David Emmanuel (1774-1808), Georgia’s 24th governor, may have been of Jewish descent. A member of Georgia’s early Jewish community, Raphael Moses (1812-1893), was a slave owner, a proponent of the South’s secession from the union, and a pioneer in the peach industry, the first grower to send his products to northern markets.

On August 16, 1915, a new and disturbing reality set in for Georgia’s Jews when a group of armed men broke into a prison cell in Atlanta and abducted a Jewish prisoner named Leo Frank. They then drove him to the town of Marietta, tied a noose around his neck, and hung him from a tree to die. Frank was the first and last American Jew to be lynched.

Two of his kidnappers were prominent citizens. Joseph Mackey Brown was a former governor of Georgia and Eugene Herbert Clay was the ex-mayor of Marietta, in Cobb county. (Interestingly enough, Ossoff’s margin of victory there was 56 to 44).

Frank, born in Texas, was the manager of the National Pencil Company in Atlanta, where the majority of Jews in the state lived. In 1913, he was convicted of having murdered one of his employees, Mary Phagan, a 13-year-old girl from Marietta. After a sensational trial, the outgoing governor, John Slaton, commuted Frank’s sentence from capital punishment to life imprisonment.

The commutation aroused a wave of anger, prompting Tom Watson — a right-wing populist and the publisher of a small journal — to call for Frank’s lynching.

This horrendous incident, rife with antisemitic overtones and undercurrents, traumatized and intimidated the Jewish community, whose roots can be traced to the 19th century. Around half of Georgia’s Jews left the state. The assimilated Jews who remained behind kept a very low profile.

A by-product of the Frank affair was the formation of the Anti-Defamation League, which monitors and combats antisemitism.

Until his dying day, Frank proclaimed his innocence. Decades later, the identity of the real murderer was established. In 1986, Frank was posthumously pardoned by the Georgia State Board of Pardons and Paroles.

New tensions arose during the civil rights movement of the 1950s and 1960s. Being careful to fit in, Jews generally observed the norms of Southern societies, but a few courageous souls stood up to injustice, braving the inevitable consequences.

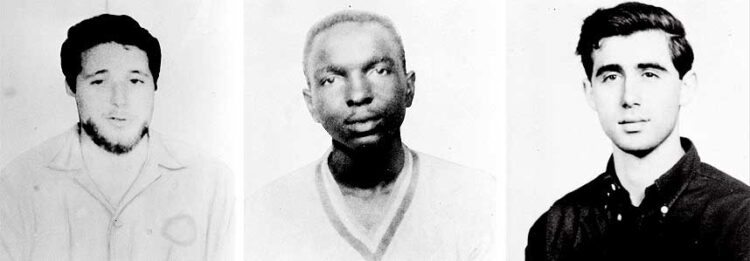

A Reform synagogue in Atlanta was bombed in 1958, the terrorists believed to have been members of the Ku Klux Klan. In 1964, two Northern Jewish civil rights workers, Andrew Goodman and Michael Schwerner, and a local African-American activist, James Chaney, were murdered by racists in Mississippi.

With normalcy returning to the South in the next decade, Sam Massell Jr. was elected mayor of Atlanta in 1970, the first Jew to hold that position.

Ossoff, a 33-year-old journalist and documentary movie maker, is acutely aware of Georgia’s legacy of racism and oppression, as is his African-American colleague, Warnock.

Until recently, a person like Warnock, a pastor, could not even dream of reaching high political office. Through constitutional amendments enacted from the 1890s onward, Southern states disenfranchised African-Americans. The federal government remained conspicuously silent as these restrictions were imposed.

“Shut the door of political equality and you close the door of social equality in the face of the black man,” James Vardaman, the U.S. senator from Mississippi from 1913 to 1919, said in a comment his white constituents would have endorsed without reservation.

A newspaper in Georgia, the Augusta Chronicle, opined in 1914 that if black people were eliminated from politics, they would understand that whites were superior.

“If blacks voted with whites as equals, they would insist on living and sleeping with whites as equals,” writes Leon Litwack in Trouble in Mind: Black Southerners in the Age of Jim Crow. “No white Southerner could contemplate such degradation.”

A Georgia feminist, Rebecca Felton, warned that white women would be endangered if black men were allowed to vote.

Such was the climate of fear among African-Americans in Dixie that a black newspaper in Savannah observed, “It is getting to be a dangerous thing to acquire property, to get an education, to own an automobile, to dress well, and to build a respectable home.”

Reflecting on Georgia’s past, Warnock said, “Georgia is such an incredible place when you think about the arc of our history. We are sending an African-American pastor of Ebenezer Baptist Church, where Martin Luther King Jr. served, and also Jon Ossoff, a young Jewish man, the son of an immigrant, to the U.S. Senate. This is the reversal of the old Southern strategy that sought to divide people.”

Congresswomen Debbie Wasserman and Brenda Lawrence, co-chairs of the Caucus on Black-Jewish Relations, issued a statement on January 8 to celebrate this transition to racial equality in Georgia:

“Georgia’s resolutely determined voters have not only secured a brighter future for all Americans by electing Reverend Raphael Warnock and Jon Ossoff to establish a Democratic majority in the U.S. Senate, but they also remedied a measure of America’s discriminatory past by electing the first African American and Jewish senators from the Peach State. This reckoning celebrates decades of struggle by countless civil rights foot soldiers and leaders inspired by the likes of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., our recently-passed Black-Jewish Caucus Co-Chair Congressman John Lewis, and Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel …

“The wonderful Black-Jewish ballot buddy story that these two senators-elect embody also reignites the vital civil rights alliance and shared values that have wedded these two communities in an enduring quest for justice, not just in Georgia, but throughout America.”