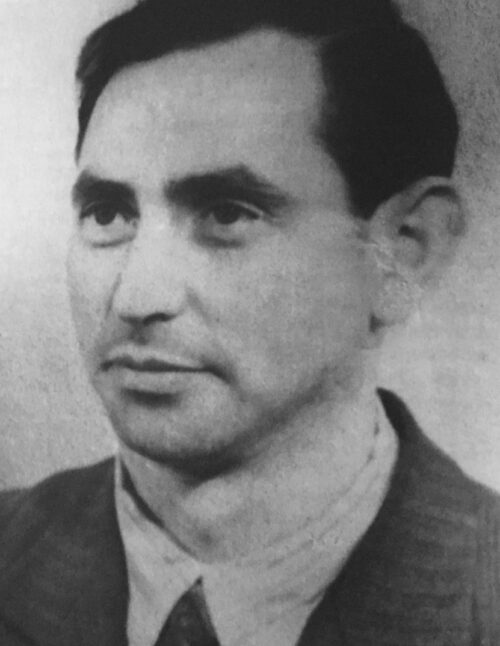

An old photograph I treasure, taken by a person whose identity will never be known, shows a solemn young couple and their two children sitting on the grass in Montreal’s Fletcher’s Field, a stone throw’s away from heavily-wooded Mount Royal.

The woman, a hint of a smile on her face, balances a toddler on her thighs, her fingers grasping the girl’s chest. The man, both feet raised jauntily and his arms hanging loosely, sits in front of a boy dressed in a sailor’s suit.

The people in the photograph are my parents, Genia and David, my younger sister, Marilyn, and yours truly. I believe it dates back to the summer of 1949, when I was three and Marilyn was several months old. My parents, then in their mid-30s, were Polish Holocaust survivors, having arrived in Canada on a frosty day in February 1948 to restart their lives.

After World War II, they found themselves in a displaced persons camp in southern Germany, which was occupied by allied armies. I was born in Bad Reichenhall, a nearby spa town in the foothills of the Bavarian Alps. All three of us left Europe by ship from the port of Hamburg. In Halifax, we boarded a train bound for Montreal, which would be our new home.

Shortly after our arrival, my father, a skilled tailor who had learned his craft in Lodz, started to work at Stein & Gerson, a ladies’ wear manufacturer near St. Catherine Street, several kilometres from our cold-water flat on St. Urbain Street.

He owed his job, as well as his admittance to Canada, to a special Canadian government program, the Garment Workers Scheme, which brought Jewish displaced persons in Europe to this country.

Devised by the Canadian Jewish Congress and the Jewish Labor Committee with the half-hearted authorization of the federal government, it was the first reversal of a grossly unfair immigration policy that had drastically limited the inflow of Jewish immigrants into Canada from the 1920s onward, write Andrea Knight, Paula Draper and Nicole Bryck in The Tailor Project, a fine account of this program published by Second Story Press.

Representing the “first crack in that wall of restriction,” it was enacted not out of compassion but out of a need to deal with an acute labor shortage in the Canadian garment industry. Described by the authors as “an achievement worth remembering and celebrating,” it permitted “a first group of several thousand Holocaust survivors and their families to begin new lives in Canada.”

And they add, “It was also a first step toward opening Canada to the admission of Jews on the same terms as others Europeans and a key step toward the eventual elimination of racial and ethnic barriers to Canadian immigration.”

As the historian Harold Troper observes in the introduction, Canada was none too eager to change its racist immigration policy. In 1947, Prime Minister William Lyon Mackenzie King stood up in the House of Commons and said, “With regard to the selection of immigrants, much has been said about discrimination. I wish to make quite clear that Canada is perfectly within her rights in selecting the persons whom we regard as desirable future citizens. It is not a ‘fundamental human right’ of any alien to enter Canada. It is a privilege.”

Canada’s Jewish population stood at 16,700 in 1900 and increased to 75,800 by 1910 thanks to an influx of Jews from Eastern Europe. Most of them settled in cities rather than rural areas, unlike Ukrainians, Scandinavians, Dutch and Germans. The few Jews who gravitated to the countryside tended to be petty merchants, tradesmen or artisans rather than farmers or industrial laborers.

Anglo and French Canadians, who comprised the bulk of Canada’s population, generally perceived Jews in a negative light, largely regarding them as a clannish, politically subversive group resistant to assimilation.

By the mid-1920s, Jewish immigration had been scaled back by means of a system that divided European countries into three separate categories. Immigrants from the “preferred” group, hailing from northern and western Europe, were exempted from restrictive provisions. “Non-preferred” immigrants, from central and Eastern European countries such as Russia, Romania and Poland, were allowed into Canada if they possessed sufficient capital and were willing to take up farming. “Special permit” immigrants, from Italy, Greece, Bulgaria, Turkey and Syria, were regarded as non-desirable. Jews were lumped into that category unless they were British subjects or from the United States.

For the next two decades, Canada was virtually closed to potential Jewish immigrants. “I fear we would have riots if we agreed to a policy that admitted numbers of Jews,” King wrote in his diary. The Canadian Jewish Congress lobbied for a fair and humane policy, but to no avail. From 1933 to 1945, fewer than 5,000 Jewish newcomers were admitted to Canada.

In July 1946, the director of the Canadian Jewish Congress, Saul Hayes, told a parliamentary committee that Canada should pass a new immigration act free of racial discrimination. King clung to the status quo, opposing “a fundamental alteration in the character of our population,” as he put it in his diary.

Yet change was in the offing. C.D. Howe, the minister of reconstruction and supply who had played a vital role in the war effort, believed that a post-war economic boom would require an influx of new immigrants within the framework of so-called bulk labor programs. The first ones to qualify for them were displaced persons who worked in lumber camps, farms, mines, railroads, construction sites and as domestics.

“Although these schemes were, in principle, open to everyone in the displaced persons camps, the reality was that ethnic stereotypes restricted many from these programs,” the authors write in a reference to Jews.

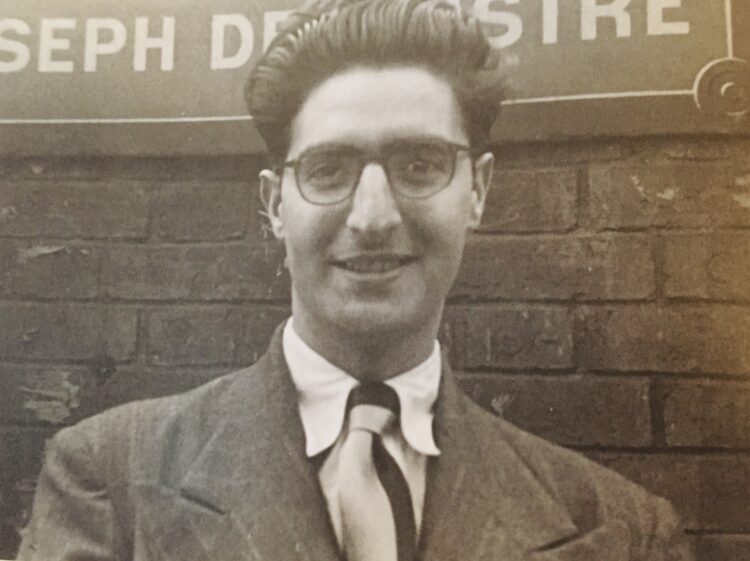

Joe Salsberg, a former union leader and the only Communist in the Ontario legislature, toured displaced persons camps and found that screening procedures were discriminatory.

Canada’s bulk labor programs, having proven to be unsuitable for the vast majority of Jews, did not go unnoticed by the Jewish community. But if the needle trades were added to the mix, Jews could easily qualify. By the 1930s, Canada’s “ready-to-wear” clothing industry was dominated by Jewish owners and workers.

Bearing this possibility in mind, Samuel Bronfman, a wealthy businessman and the president of the Canadian Jewish Congress, finagled a meeting with King and his ministers in the winter of 1947. He argued that manpower shortages in the garment industry, centered in Montreal, Toronto and Winnipeg, could be alleviated if Jews in displaced persons camps in occupied Germany were permitted to immigrate to Canada.

King was noncommittal.

In response, clothing manufacturers, in conjunction with union and Jewish community leaders, launched a coordinated campaign to convince the government that the fate of the garment industry and the vitality of the economy hinged on the importation of Jewish tailors in displaced persons camps. “We are having tremendous difficulty securing tailors for our industry,” David Dunkelman, the founder of Tip Top Tailors in Toronto, wrote in a letter to the minister of labor.

Requesting that 2,000 workers and their families be admitted to Canada, a Jewish delegation dispatched to Ottawa promised officials that the costs of selecting, transporting and settling the new arrivals would be borne by the garment industry. In fact, these costs would be shared by employers, the Canadian Jewish Congress and the Jewish Immigrant Aid Society.

In October 1947, the admission of 2,136 tailors was officially approved by order-in-council 2180, subject to immigration, security and health screenings. Selected from 38,000 mostly Jewish garment workers among 240,000 displaced persons, 90 percent of them were Jewish.

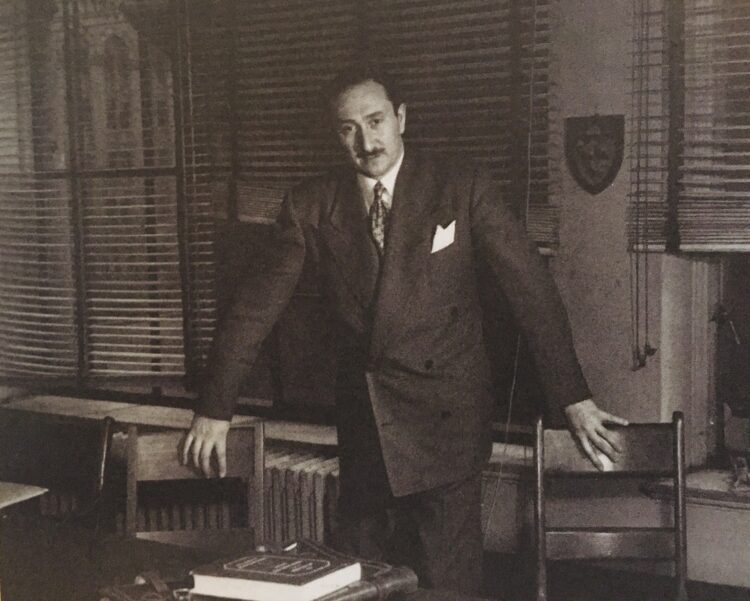

They had been chosen by a five-man commission which visited the displaced persons camps: Max Enkin, the president of Cambridge Clothes and of the National Council of Clothing Manufacturers; Samuel Herbst, the business manager of the International Ladies’ Garment Workers’ Union, Samuel Posluns, a member of the Cloak Manufacturers’ Association of Toronto, Bernard Shane, the treasurer of the Jewish Labor Committee, and David Solomon, the executive director of the Manufacturers’ Council of the Ladies’ Coat and Suit Industry.

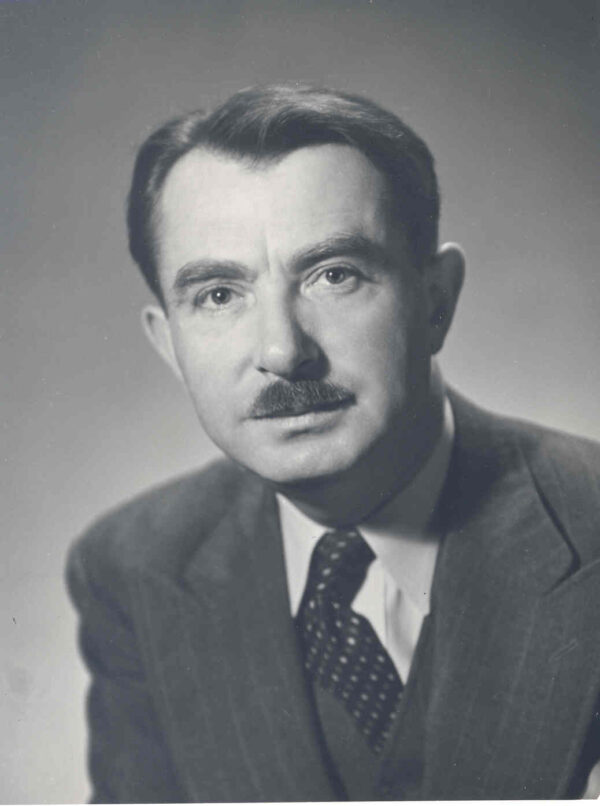

Enkin, who had been instrumental in the founding of the Jewish Vocational Services agency in Toronto in 1947, led the team. Matthew Ram, a young social worker from Montreal who had been hired by the Canadian Jewish Congress to work with the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee in the camps, kept the project on track.

On the eve of their departure for Europe, they were informed that Howe objected to the preponderance of Jews in the program. On Howe’s instructions, Labor Minister Arthur MacNamara conveyed this message to the commission’s lawyers, J.J. Spector and Norman Genser, who were both shocked to hear such a bold articulation of the government’s aversion to Jewish immigrants.

Howe, meanwhile, relayed the same message to Enkin: “Under no circumstances could they proceed with this scheme if there were more than 50 percent Jews selected.”

The commission contemplated raising an outcry, but resigned itself to “half a loaf” rather than none.

With the addition of dependents, some 6,000 displaced persons eventually came to Canada under this project, with the first batch of Jewish tailors arriving at Halifax’s Pier 21 and Quebec City in January 1948.

Fifty five percent of thee new arrivals went to Montreal, 36 percent to Toronto and the remainder to Winnipeg and Vancouver.

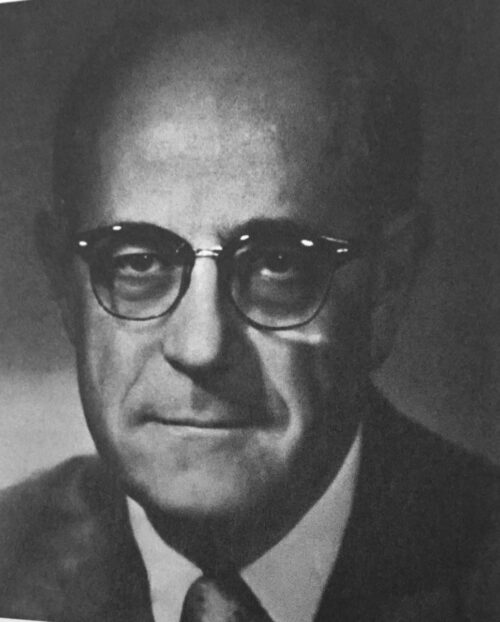

The most comprehensive resettlement program was developed in Montreal, the authors say. The refugees were provided with temporary housing and financial assistance. Joseph Kage, the director of social services for the Jewish Immigrant Aid Society, created an innovative program to help the survivors grapple with psychological problems caused by their traumatic experiences.

Toronto’s Jewish community was not as well prepared. When the first group of tailors and their families arrived at Union Station on January 18, 1948, there was no one to greet them, and only limited housing was available. These problems were immediately fixed.

The authors offer readers portraits of the newcomers.

Irving Leibgott, from the Polish town of Plock, opened a valet tailoring service in Montreal. Mendel Beklier, a native of Grojec, Poland, started a job at Tip Top Tailors in Toronto, but soon began working as a shoemaker in a factory. Judy Cohen, a Hungarian Jew from Debrecen, became a sewing machine operator in Montreal. Mendel Good, who was born in Nowy Sacz, Poland, earned a living as a tailor in Ottawa. Yudel Najman, from Stok, Poland, was a presser in Montreal.

New Canadians like them, representing 10 percent of the 165,000 displaced persons who streamed into Canada after the war, were the first large group of Holocaust survivors to settle in this country. “They were soon followed by DPs who joined other labor programs initiated by the Jewish community, notably by the furrier and hat-making industries,” the authors say.

Thanks to these programs, thousands of European Jews, including my late parents, were given a new lease on life, for which they were forever grateful.