The pro-German Vichy government in France enacted antisemitic legislation with the full knowledge and support of the Catholic church, says a Canadian scholar who’s currently writing a book about that charged topic.

Aliza Luft, an assistant professor at the University of California’s campus in Los Angeles, made this claim at a zoom lecture recently sponsored by the Anne Tanenbaum Centre for Jewish Studies at the University of Toronto.

Luft’s forthcoming work, Sacred Treason: How Catholic Bishops Defected From Vichy To Save Jews During The Holocaust, is scheduled to be published by Harvard University Press.

The Vichy regime, headed by Marshal Philippe Petain, voluntarily passed rigorous anti-Jewish laws in 1940 and 1941 without coercion from Germany. Known as the Statut des Juifs, they deprived Jews of their rights and citizenship, nullified the civic gains they had made since emancipation in the late 18th century, and created the conditions for their deportation to Nazi internment and extermination camps.

French Jews in Algeria, Morocco and Tunisia were also affected by these laws, which were based on German ordinances.

The Catholic church in France, which wielded immense authority and influence, endorsed Vichy’s hostility toward Jews and remained conspicuously quiet as Jews were demonized, marginalized, persecuted and deported to their deaths.

A deadly combination of silence and violence doomed the besieged Jewish community of France, the first one in Europe to be emancipated, Luft suggested.

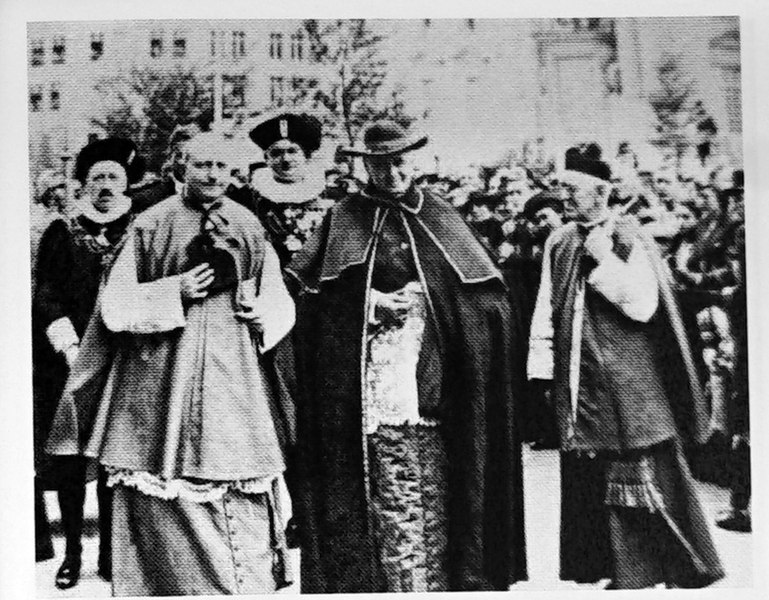

One of France’s leading cardinals, Pierre-Marie Gerlier of Lyon, was explicitly supportive of the Statut des Juifs. In December 1941, he declared, “No one more than I recognizes the evil that Jews have done to France.”

Such was Gerlier’s fealty to Vichy that he declared, “Petain is France and France is Petain.”

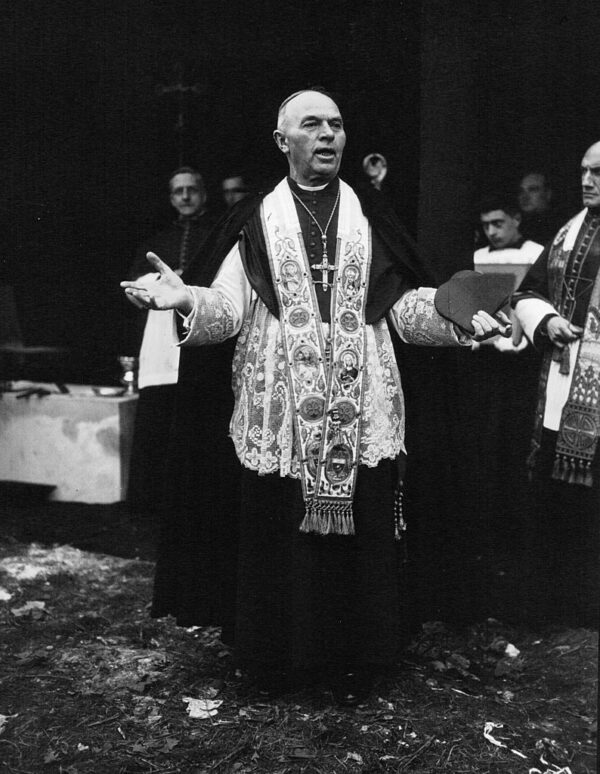

Still other cardinals, like Emmanuel Suhard of Paris, chose to remain silent after being arrested and accused of plotting against Germany, said Luft. Bishops and priests followed his lead, whatever qualms or reservations they may have harbored, she added.

Suhard’s deafening silence and Gerlier’s outspokenness converged into an endorsement of Vichy antisemitism and helped shape church policy with respect to the persecution of Jews.

From 1933 to 1939, however, many French bishops denounced Nazi Germany’s mistreatment of its Jewish citizens. But as circumstances in France and Europe changed, the position of the French church toward Jews gradually shifted, Luft said.

The death of Cardinal Jean Verdier — who had denounced the Kristallnacht pogrom in Germany in 1938 and was on friendly terms with Leon Blum, France’s first Jewish prime minister — removed from the scene a vocal and respected opponent of antisemitism. He died in April 1940, about six months before the first antisemitic law was promulgated.

The appearance of a new pope, Pius XII, on the eve of World War II strengthened elements in the church hierarchy seeking cordial relations with Germany.

And after Germany’s conquest of France, the country was divided into various zones, making it more difficult for bishops to communicate easily.

Due, in part, to these developments, the French church was generally receptive to the Statut des Juifs. But as Luft noted, progressive priests rejected Vichy’s antisemitic campaign. Citing an example, she mentioned Gaston Fessard, who in 1941 denounced the church’s collaboration with Vichy.

In the summer of 1942, a group of liberal-minded bishops in southern France condemned Vichy’s antisemitism. Luft claims that their denunciation of the Statut des Juifs was a turning point in the church’s heretofore hostile or indifferent attitude toward the persecution of Jews.

Around the same time, the archbishop of Toulouse, Jules-Geraud Saliege, proclaimed that “the Jews are our brothers,” a comment that was repeated by other bishops and priests throughout France.

As for Gerlier, he was in favor of Vichy’s “protective measures” against Jews, but maintained that its policy should be guided by the rules of justice and charity, said Luft. In a direct reference to Jews, Gerlier said, “They belong to mankind … No Christian dare forget that!”

Acting in this spirit, Gerlier condemned Vichy’s deportation of Jews to Nazi death camps in Poland and asked Catholic religious institutes to shelter Jewish children. By Luft’s reckoning, he saved 108 children from being deported to Poland.

In Luft’s estimation, Gerlier represented both sides of the coin –the compassionate and the dark side of the church.

As she put it, “He is emblematic of this behavioral variation during the Holocaust. He praised Vichy and was complicit in its collaboration with the Nazis, yet he protested on behalf of Jews and supported efforts to save them.”