When World War II ended in May of 1945, several million displaced Europeans, ranging from forced laborers to prisoners of war, found themselves in Germany, which Allied bombing raids had devastated and which was now occupied by American, British and Soviet armies.

The vast majority of the refugees were repatriated to their respective homelands in short order, but one million, fed, sheltered and protected by the United States and Britain, refused to go back home, leaving the Allies with an immense and costly refugee problem.

The Poles, Ukrainians, Lithuanians, Latvians and Estonians in this group, comprising two-thirds of the recalcitrant displaced persons, were loathe to return because their countries were governed by communist regimes and enmeshed in the Soviet sphere of influence. They preferred to be resettled in Western democratic nations.

The Polish Jews, eager to leave Germany, hoped to immigrate to Palestine — which was administered by Britain and which was on the cusp of the first Arab-Israeli war — or to Western countries like the United States or Canada.

It took several years to sort out these problems, but in the meantime, the refugees were trapped in Germany, living in autonomous displaced persons camps with their own self-governing bodies, police forces and schools.

David Nasaw, an American historian, tells their story exceedingly well in The Last Million: Europe’s Displaced Persons From World War To Cold War, published by Penguin Press. I have a special interest in this topic because I was born near a DP camp in southern Germany where my Polish Jewish parents, David and Genia, lived for several years after the Holocaust.

As Nasaw points out, the fate of the DPs was essentially in the hands of two major powers, Britain and the United States, which supported their right to refuse repatriation until they could be resettled properly.

The Soviet Union and its Eastern European allies, desperately short of a viable labor force to rebuild their shattered economies, demanded the closure of the DP camps and, with the exception of the Jews, the transfer of their inhabitants to their countries of origin.

By Nasaw’s estimate, upwards of 250,000 Jewish DPs streamed into Germany shortly after the defeat of the Nazi regime. Most were Polish Jews. A minority, having endured extermination camps or having gone into hiding, were Holocaust survivors. The greatest number, having fled to the Soviet Union following Germany’s conquest of Poland in 1939, returned to their homes from the summer of 1945 onward. Feeling generally unwelcomed in Poland and intimidated by antisemitic violence and pogroms in Krakow and Kielce, tens of thousands packed their bags and migrated to Germany en route to Palestine or the West.

Soon after the war, U.S. President Harry Truman reached the conclusion that the DPs, especially the Jewish ones, would have to be moved out of western Germany, which was being converted into a frontline state facing the Soviet Union and its allies. “Their removal from Germany was a precondition to the establishment of a sovereign, self-ruling West Germany, without which the coming Cold War could not be won and economic stability returned to Europe,” writes Nasaw.

Truman believed that this objective could not be accomplished unless the British allowed Jewish DPs into Palestine. One of his special envoys, Earl Harrison, recommended that they should be given the option of immigrating to Palestine. When Truman realized that Britain would not budge on this issue, he decided that the United States had no alternative but to admit a “fair share” of the refugees, Jewish or otherwise.

The DPs were ultimately dispersed in about a thousand ethnically homogeneous camps in the U.S. and British occupation zones in Germany and, to a much lesser extent, in Austria and Italy.

Jewish DPs were concentrated in Bergen-Belsen — from which my parents were liberated — Feldafing and Landsberg. Enclosed within mesh-wire fences, these camps were like East European shtetls, with their own administrations, political parties, health care systems, newspapers and education and cultural facilities.

“The camps were a way station, a transition point for the survivors who dreamed of the day they could leave Germany and Europe for a new life in a new world, hopefully in the Jewish homeland in Palestine,” says Nasaw.

There was a heartbreaking absence of Jewish children, one million of whom had been murdered during the Holocaust. Almost without exception, the survivors were between the ages of 16 to 45. The Jewish birthrate increased dramatically from 1946 onward. “The rash of marriages, pregnancies and babies collectively represented a conscious affirmation of Jewish life, as well as definitive material evidence of survival,” Nawsaw notes.

Jewish DPs lived in squalor until conditions gradually improved. When the American general, George Patton, passed through one of these camps, he vented his antisemitic animus. In a reference to Earl Harrison, he wrote, “Harrison and his ilk believe that the Displaced Person is a human being, which he is not, and this applies particularly to the Jews who are lower than animals.”

Patton’s superior, General Dwight Eisenhower, a future U.S. president, was empathetic and compassionate. “The Jews were in the most deplorable state,” he wrote in his wartime memoir, Crusade in Europe. “For years they had been beaten, starved and tortured.”

Truman was sympathetic, too. He asked the British government to issue 100,000 certificates to Jewish DPs intent on settling in Palestine. Britain, fearing an Arab backlash, rejected his proposal. So in 1948, the United States began admitting DPs, but the congressional bill which facilitated their entry was prejudicial against Jews. In 1949, more balanced legislation was passed, enabling 57,000 Jewish DPs out of 328,000 to enter the United States.

The Truman administration, gearing up for the Cold War with the Soviet Union, knowingly permitted Nazi collaborators and fascists, all of whom were fanatical anti-communists, into the United States. One of them, Viorel Trifa, was a cleric who had been a leader of Romania’s Iron Guard militia, which committed war crimes during the Holocaust. Trifa became a governor of the board of the National Council of Churches. And in 1955, Richard Nixon, the vice-president, invited him to address a session of the U.S. Senate.

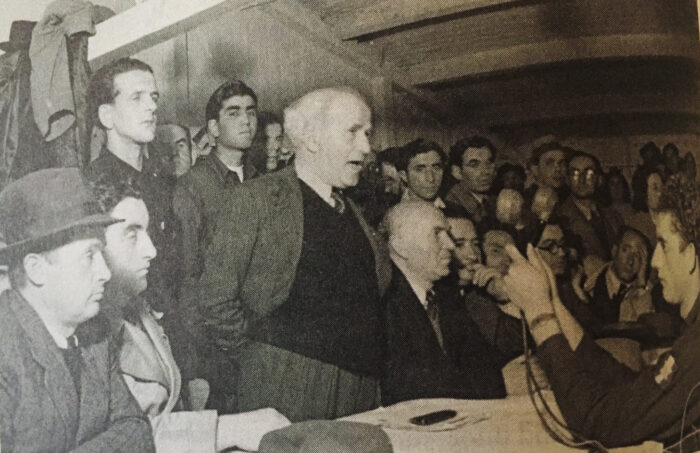

From the outset, the Jewish leadership in Palestine sought to attract DPs. In 1946, David Ben-Gurion, the chairman of the Jewish Agency, visited several camps to drum up enthusiasm for the Zionist cause. His appeal worked. DPs would add 16.5 percent to Israel’s population.

After the outbreak of the first Arab-Israeli war in 1948, thousands of young Jewish men in the camps departed for Israel. “The war depends on immigration because the manpower in Israel will not suffice,” said Ben-Gurion.

According to Nasaw, 22,000 Jewish DPs fought in the War of Independence, comprising one-third of Israel’s combat soldiers and one-third of its casualties.

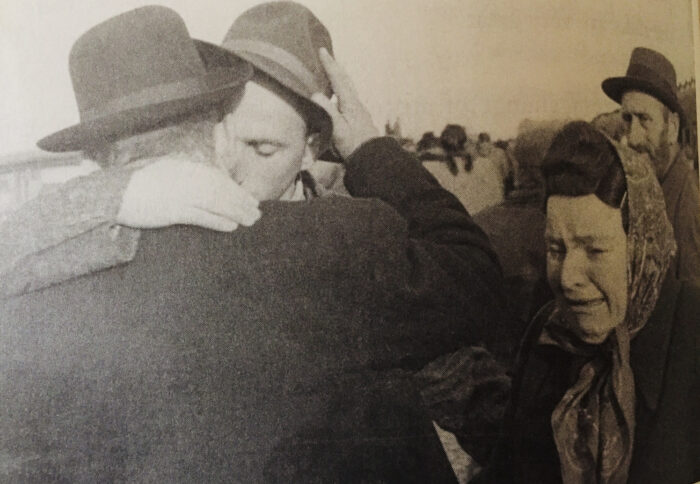

DPs also flocked to Latin America. Out of 30,000 DPs who settled in Brazil, 2,000 were Jews. Australia admitted 182,000 DPs, of whom 8,000 were Jews. Seven thousand Jewish DPs arrived in Canada in 1948. Three of the newcomers were my parents and I. We landed in Montreal, via Hamburg and Halifax, in February 1948.

In line with Allied police, the camps were incrementally closed. Bergen-Belsen and Landsberg were shuttered in 1950, while Feldafing ceased to exist in 1951, bringing to an end a unique footnote in European history, an era that Nasaw documents with care, precision and skill.