I used to be a big sports fan, but nowadays I seldom follow sporting events. When I do watch sports on television, I tune in to the track and field program at the summer Olympic Games or to the World Cup, the championship of soccer.

So when I read that Netflix was planning to broadcast a documentary on Pele, the great Brazilian soccer star, I marked it down on my calendar.

Pele is one of the immortals. In a career spanning almost 20 years, he scored a record 1,283 goals in 1,367 games and is still the only player to have appeared with three World Cup winning teams.

Nearly five decades after his retirement, he continues to be regarded as the king of the game, perhaps its finest ever player. He was poetry in motion, a consummate professional who helped establish Brazil as a force to be reckoned from the late 1950s to the early 1970s.

Netflix’s cinematic portrait, titled Pele, does not always live up to expectations. It tends to be a tad pedestrian, but it’s an acceptable piece of filmmaking, particularly the last 15 minutes.

Pele, now just over 80, appears in a bare studio within minutes of its opening scenes. Surprisingly, he uses a walker to reach his seat. No explanation is offered for his infirmity, but I suppose his injuries on the field have taken a toll.

Pele, whose real name is Edson Arantes do Nascimento, was born in 1940 into an impoverished family. “We came from nothing and had very little,” he recalls. Aspiring to be as good a player as his father, he was recruited by the Brazilian club Santos when he was only 16. “He showed amazing talent,” says one of his peers.

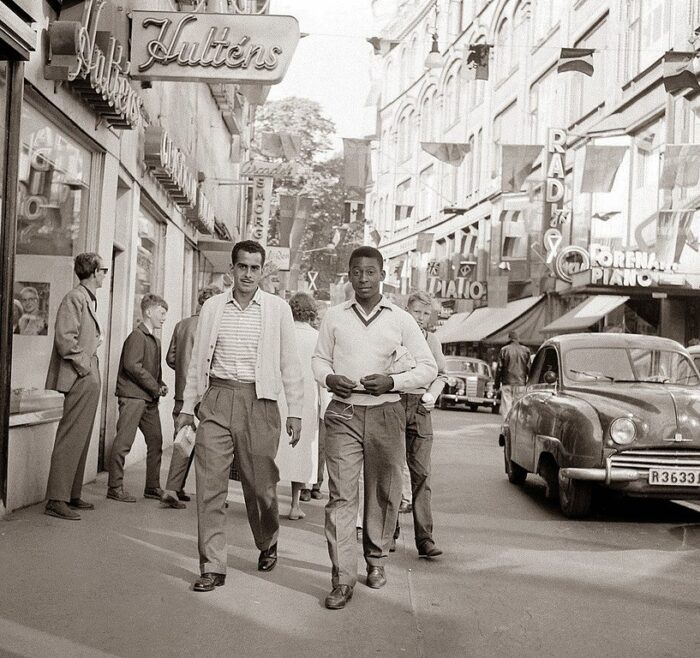

In his first trip abroad, Pele, who wore a jersey with the number 10 emblazoned on it, went to Sweden to play for the Brazilian national squad at the 1958 World Cup. He acquitted himself well. In the final, Brazil defeated Sweden, causing an outpouring of joy in Brazil. Pele cries when he remembers that tournament.

From that moment onward, he was treated like a hero and regarded as a role model for poor black boys. Unfortunately, the film says nothing about the place of black people in Brazilian society, then and now.

Be that as it may, Pele’s leap to fame and fortune coincided with the ascendancy of television in Brazilian homes, the commentator observes.

At the 1962 World Cup, Pele was injured in one of the first games and missed the rest. Brazil managed without him, defeating Czechoslovakia and capturing the World Cup.

Pele’s fortunes were unaffected by the 1964 military coup, which ushered in a lengthy period of domestic repression. During this period, he got married, but was not a faithful husband, indulging in extramarital affairs and producing a crop of illegitimate children.

Much to its bitter disappointment, Brazil was eliminated in the early stages of the 1966 World Cup, which England won on home turf. To the shock of his fans, Pele announced it was his last World Cup appearance.

The ruling junta convinced or pressured him to join the national team one last time for the 1970 World Cup in Mexico. Complications emerged when the coach sidelined Pele, claiming he was short-sighted. In short order, the coach was sacked and replaced.

This segment of the film brims with suspense and excitement. In what would be his last World Cup, Pele was brilliant. En route to victory, Brazil beat England 1-0, Uruguay 3-1 and Italy 4-1.

Pele played his last game for Brazil in 1971, but continued scoring goals for Santos until 1974. For a while after that, he played for a team in New York City, but this chapter is glossed over perfunctorily. And much to its detriment, the film inexplicably ignores his life since then.