It was recently announced that Jews in the Persian Gulf have formed the first communal organization, the Association of Gulf Jewish Communities. It will cater to the religious and educational needs of Jews in the United Arab Emirates, Bahrain, Kuwait, Oman, Qatar and Saudi Arabia, all of which are officially pro-Western and aligned with the United States.

This is an historically significant development, given the trials and tribulations that Jews from Arab lands endured before and after the birth of Israel in 1948.

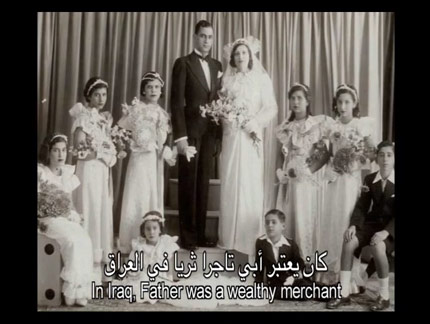

With the United Nations having approved the 1947 Palestine partition plan, venerable Jewish communities in Arab states were placed under immense strain and stress. Jews were subjected to a campaign of intimidation and violence, which was often orchestrated by anti-Zionist nationalist governments. They had little alternative but to leave their homelands.

Jews in countries ranging from Syria, Iraq and Egypt to Morocco, Tunisia and Yemen were demonized as potential traitors and forced to emigrate, leaving behind empty schools and synagogues and centuries of memories.

Israel, hungry for new immigrants, encouraged their mass departure. More than 500,000 Jews left voluntarily or were forced out by various means.

A succession of Arab-Israeli wars, from the Sinai War in 1956 to the Six Day War in 1967, aggravated the tenuous situation of Jews still remaining in the Arab world.

In Syria, Hafez al-Assad’s Ba’athist regime restricted the civil rights and the movements of the last remaining Jews. In Egypt, President Gamal Abdul Nasser imprisoned hundreds of Jews. And in Iraq, where a 1941 pogrom in Baghdad resulted in the murder of 180 Jews, the crackdown on Jews was particularly severe.

I witnessed the effects of these seminal changes while on a reporting assignment in Syria and Egypt in 1975 and during personal trips to Morocco and Algeria in 1978.

In Damascus, Jews lived in a virtual state of uncertainty and fear, waiting for the day when they could resettle abroad. In Cairo, synagogues were shuttered, schools were closed, and a Jewish cemetery I visited was in deplorable condition.

Touring the old quarter of Algiers, near the steps leading to the fabled casbah, my friend Henry Srebrnik and I persuaded a janitor to unlock the door of a small abandoned synagogue. Scattered on the floor were Jewish prayer books gathering dust.

The sight of these mouldering texts reinforced my belief that no one can accurately predict what lies around the next corner, especially in a volatile and unpredictable place like the Middle East.

Visiting the Moroccan cities of Fez and Marrakesh, Henry and I learned that Jewish parents were sending their sons and daughters to study in Europe, Canada and the United States, knowing full well they would not return. There was simply no future for Jews in an Arab country, they told us with a mixture of sadness and regret.

They were right, of course. More than four decades on, Morocco’s Jewish population is down to 2,000 to 3,000 from a high of 250,000 in the late 1940s.

As for the Jewish communities in Algeria, Syria and Egypt, they have vanished, swept away by the acrimonious politics of the Arab-Israeli dispute and Israel’s conflict with the Palestinians.

The very small Jewish communities in the United Arab Emirates and Bahrain were not exempt from the wave of suffering that afflicted Middle Eastern Jews. But they managed to preserve their communities because their pragmatic royal rulers were not fanatical Arab nationalists and appreciated their presence.

These sheltered Gulf communities have been doubtlessly strengthened by the historic normalization agreements signed by Israel and the United Arab Emirates and Bahrain last summer.

As far as I know, there are no organized Jewish communities in Oman, Qatar, Kuwait and especially in Saudi Arabia, the seat of Islam. Only Jewish diplomats, businessmen and military personnel are temporarily stationed in these countries. But the Association of Gulf Jewish Communities is likely to be helpful to these expats.

Funded by private donors, the association is led by Rabbi Elie Abadie, who was born in Beirut, raised in Mexico City and educated in New York City. His parents fled the city of Aleppo in the wake of anti-Jewish riots in Syria following the passage of the 1947 Palestine partition resolution.

While there are several thousand Jews in the entire Arab world today, Iran’s Jewish community of about 15,000 is the largest in the Muslim world. Before the 1979 Islamic revolution, the 42nd anniversary of which was marked last month, more than 100,000 Jews lived in Iran.

Although Iran is unofficially at war with Israel, Iranian Jews are not persecuted, enjoy religious freedom and are protected by the regime.

Nonetheless, as the Anti-Defamation League points out in a recent report, the first comprehensive study of its kind, Iranian school texts are filled with antisemitic material and anti-Zionist screeds.

The anti-Jewish references, pertaining to the earliest period of Muslim history, claim that Jews conspired against Mohammed the Prophet, attempted to sabotage the Islamic order, and collaborated with the enemies of Islam.

The last two accusations are eerily similar to those that drove Jews out of Arab nations after the establishment of Israel. The Iranian regime is surely guilty of planting the seeds of antisemitism in its youth.